This is the draft website for Programming Historian lessons under review. Do not link to these pages.

For the published site, go to https://programminghistorian.org

Contents

- Introduction: A Small Collaborative Publishing Ecosystem

- Setup

- Authoring and Editing

- Reviewing and Publishing

- Drawbacks and Limitations

- Moving an existing website to Jekyll

- Help

- Acknowledgements

- Footnotes

Introduction: A Small Collaborative Publishing Ecosystem

This lesson is for you if you want to turn a basic Jekyll-generated website into a digital humanities community blog or other multi-author scholarly website, such as a simpler version of the ScholarsLab.org DH center website and blog. The “Building a static website with Jekyll and GitHub Pages” lesson taught scholars how to create an entirely free, easy-to-maintain, preservation-friendly, secure website over which they’d have full control, such as a scholarly blog, project website, or online portfolio. In this second lesson, we provide novice-friendly instructions on how to turn that basic Jekyll website into an active, community-authored blog with a system for reviewing writing and other site changes before moving them to the visible website1.

The tutorial is divided into two parts: some initial, one-time steps, and the steps you’ll follow each time you want to author or edit the site. This lesson will cover creating and editing blog posts on your site, and creating and integrating author information for sites supporting multiple authors. We also offer practical advice for the challenges this sort of set-up offers for community authorship as well as questions you should consider before undertaking this sort of workflow. If you have an existing blog you’re hoping to migrate to Jekyll, we briefly advise on this process near the end of this lesson, but do not cover this topic in depth.

Pre-requisites and requirements

This lesson assumes you’re starting from an existing Jekyll website you’ve created yourself, either by:

- completing The Programming Historian’s “Building a static website with Jekyll and GitHub Pages” lesson, or

- otherwise setting up a basic Jekyll-generated website hosted on GitHub Pages, and understanding how to work with it locally using the GitHub Desktop app and your command line (topics covered in that lesson).

You will start from a copy of the https://github.com/amandavisconti/jekylldemo repo (which runs a site that looks like https://amandavisconti.github.io/JekyllDemo), and you’ll end up with a repo that looks like https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo and a site that looks like https://scholarslab.github.io/CollabDemo.

You may be able to follow this lesson using any kind of computer plus monitor and keyboard, but this lesson is written from a Mac perspective and does not cover some specifics of Windows and Linux use. You’ll also need a steady internet connection that can support downloading software. This lesson was written for and tested against:

- Ruby version 2.3.0

- Jekyll version 3.3.0

- The GitHub interface as of September 2019

- The Netlify interface as of September 2019

In the version of this lesson that we use for our research center’s blog, users tend to need 1-1.5 hours to complete the entire lesson.

How difficult is this lesson?

Whether learning these skills will feel comfortable and/or worthwhile to you is particular to each person’s experiences and interests. What we can tell you is that the steps in this tutorial are unambiguous. That is, there are very few choices you need to make as you work through this lesson. We tried to make this tutorial very detailed, combining actual do-something-now steps with text explaining why you’re doing these steps. We also included screenshots, so you can compare what you’re seeing with what the lesson thinks you should be seeing. A help section includes a handy recap of the steps described below (for once you understand them and just need a ready reference) and links to a terminology glossary (e.g. what’s a merge, again?) and further reading.

You’ll learn some new terms and get familiar with the GitHub.com interface. You will not need to use the command line nor understand git/versioning. (We’ll discuss two versioning concepts briefly, but you will not need to understand these to use this tutorial.)

Scholarly case study: DH center research blog

This lesson’s case study centers on https://ScholarsLab.org, a collaboratively authored, scholarly blog and web presence for which this lesson’s authors are key contributors. The Scholars’ Lab is the University of Virginia Library’s internationally recognized community lab for the practice of experimental scholarship in all fields, informed by digital humanities, spatial technologies, and cultural heritage thinking.

In early 2019, the lab relaunched this website to improve its welcome, accessibility, and clarity of how our website informs scholars at UVA and beyond about our in-progress and completed scholarship. As part of this redesign, we migrated the site from WordPress to a Jekyll-generated static site moderated through GitHub, which led to the collaborative creation of documentation to help our community members continue to blog. This community includes our 13 staff, a yearly cohort of around 50 students in formal roles, and a variety of other students, staff, and faculty collaborators. Technical knowledge among the blog’s potential authors ranged from none to expert-level, so retaining everyone’s ability to comfortably publish on our site was a critical goal.

The migration decision used minimal computing thinking to weigh the benefits of WordPress (novice-friendly blogging and content editing dashboard, widgets/plugins) against its downsides (e.g. sysadmin upkeep such as monthly or weekly code updates). Scholars’ Lab’s focus on working with rather than for our collaborators, and on HTML, CSS, git/GitHub, and Markdown as foundational knowledge for digital scholarship, both influenced our decision to move from WordPress to Jekyll. In doing so, we traded fewer folks needing to exert more effort to run the website for more folks needing to each expend less learning effort on the site. Our migration added a review process where there previously was none, using GitHub’s permission settings and pull request process to allow writers to request a read-through or feedback from other community members before publishing work where anyone can read it.

ScholarsLab.org offers a springboard to explain the scholarly motivations behind technical choices in this lesson, but the website you’ll actually develop over the course of this reading will be considerably smaller and simpler. You’ll have a site where multiple authors can blog and edit webpages, but we won’t teach you in this lesson how to change the visual design of your website or how to add other functionalities (see the Drawbacks and Limitations section for more information). We will, however, touch upon a number of features and issues relevant to developing a collaborative blogging environment based on Jekyll.

Why might this setup fits your needs?

Using a blog as a collaborative research notebook is a good way for a small, committed group of scholars to share their ongoing work with the scholarly community and public. Research shows that open publishing does not inhibit additional publication through more traditional scholarly channels2, and, in digital humanities in particular, it is not unusual for exemplary blog posts to find their way into peer-reviewed journal articles and essay collections3. Publishing ongoing work in this way can help your group to control when and how your work gets distributed to others you can learn from and build on it.

Collective blogging platforms are ubiquitous thanks to platforms like WordPress, but this lesson is designed to give you more direct control over the blogging pipeline than a commercially hosted solution (e.g. WordPress.com) or a self-hosted but complex software suite (e.g. WordPress, Drupal). Designing your own blogging ecosystem gives you and your collaborators more oversight of the mechanisms by which your research reaches the world. In the case of the Scholars’ Lab, our workflow has allowed us to more easily collaborate on series of posts with one another and with colleagues from other institutions. Because we control the technical infrastructure, we can design the blogging environment to meet our needs rather than the other way around. When working in a platform like Jekyll you trade ease of use for distributed labor: a tradeoff not to be taken lightly.

Using a static-site approach like Jekyll can help some sites be more secure and load faster, compared to sites built on WordPress and other complex content management systems (CMSs). Out of the box, Jekyll has fewer total files and lines of code behind the site, which can make it easier for more people to fully grasp what that code does, and faster for the site to load even on less reliable internet connections. CMSs are often more vulnerable to spam and hacking because of weaknesses in database security, commenting systems, and a proliferation of plugins and themes that are easy to install but harder to fully vet before installation or upgrading. Static sites are not invulnerable to attacks, however, and can easily become bloated (e.g. by adding lots of media files, complicated search features, or Javascript). The key differences between static sites and complex solutions like CMSs are in what you start with (a smaller set of code) and what that foundation makes easy to do (more fully understand your own simple site, without relying on a lot of code you don’t fully understand or need that can slow your site or open it to attacks).

This lesson will offer cautionary tales, advice for how to successfully navigate such a setup with users of varying skill sets, and a supportive workflow designed to accommodate those needs.

This lesson uses GitHub because it’s free and was the best fit for our scholarly case study’s needs, but you may wish to research the features of comparable opensource, free (e.g. GitLab) and paid (e.g. hosting on your own servers4) options for versioning and web hosting[^5].

Setup

Before starting collaborative writing and publishing on your site, you’ll need to follow the one-time setup steps below to make sure you’re working from the same set of files as the authors, set up a way to view your site changes before publishing them, allow your site to handle multiple authors, and set reviewer permissions.

Import the demo repo

To make sure you’re working from the same files and settings as we are, this lesson will have you work from a demo set of code[^6].

Download a ZIP file of the code we’ll work from by clicking on this link. This code represents the end state of the site produced by the previous Programming Historian lesson on Jekyll.

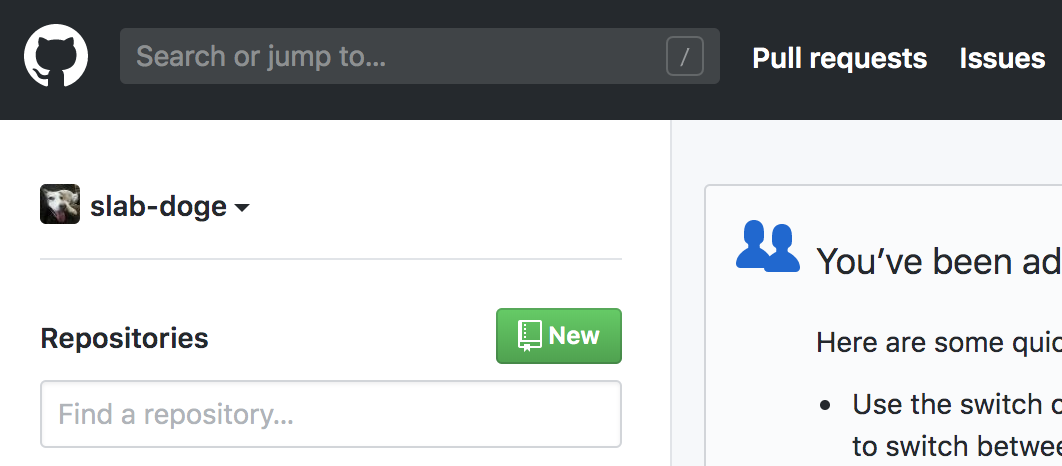

Log into GitHub. On the upper lefthand of https://github.com, click on the green “New” button.

Screenshot of the creating a new repository

In the “Repository name” field, write a short name for your repository. We recommend “CollabDemo”, as this matches the demo repo we set up.

Skip all other options on the page and click on the green “Create repository” button at the bottom of the page.

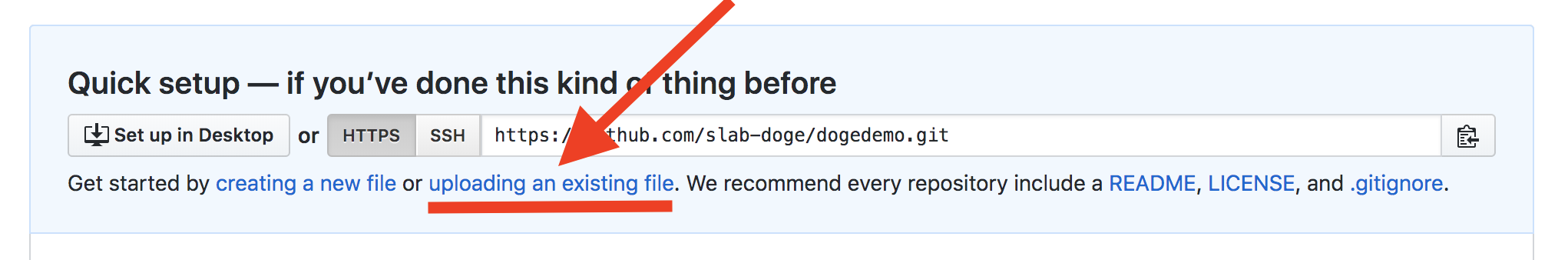

Under the “Quick setup” section, click the “uploading an existing file” link.

Screenshot of the link to upload the demo ZIP file

Double-click on the ZIP file to unzip/decompress it. Inside the resulting folder, select all the files at once and drag them onto the screen (where it says “drag files here”). Click the green “Commit changes” button at the bottom left.

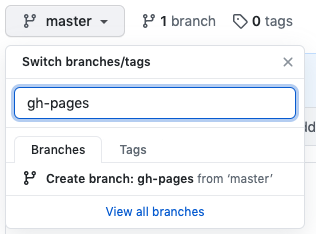

GitHub will return you to the main page for your repository, now complete with all your uploaded files. We have one last thing to do; we need to make a new branch (copy of our files) called “gh-pages” that GitHub will specifically use for publishing your site. Click the “branch:master” button, type in “gh-pages”, and then click the button that appears offering to create a gh-pages branch for you.

Creating a gh-pages branch in the GitHub interface

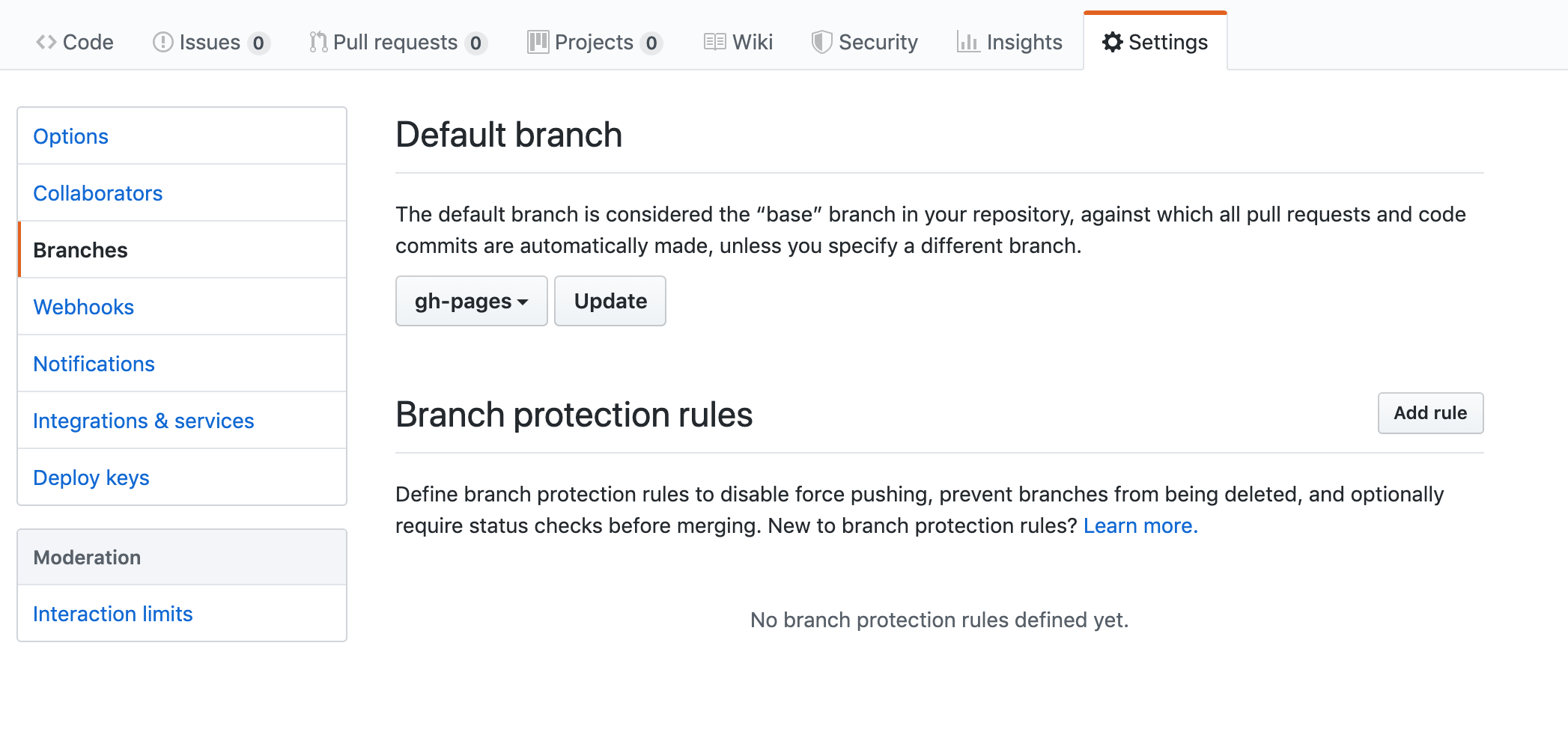

Lastly, let’s make “gh-pages” your default branch by selecting the settings tab from the top menubar, selecting branches from the left sidebar, and looking for the section titled “default branch”. Change “master” to “gh-pages” and click update. You’ll need to confirm your choice.

Update your default branch to gh-pages for the repo

In this lesson, when we write a link that includes https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo, please replace “scholarslab” with your GitHub username, and “CollabDemo” with whatever you named your repository above.

Set up Netlify

Netlify is a service that will allow you to preview new content submitted by your collaborators before making it a part of your website. This makes it easier for people of varying technical levels to contribute to your project, but it requires a bit of setup.

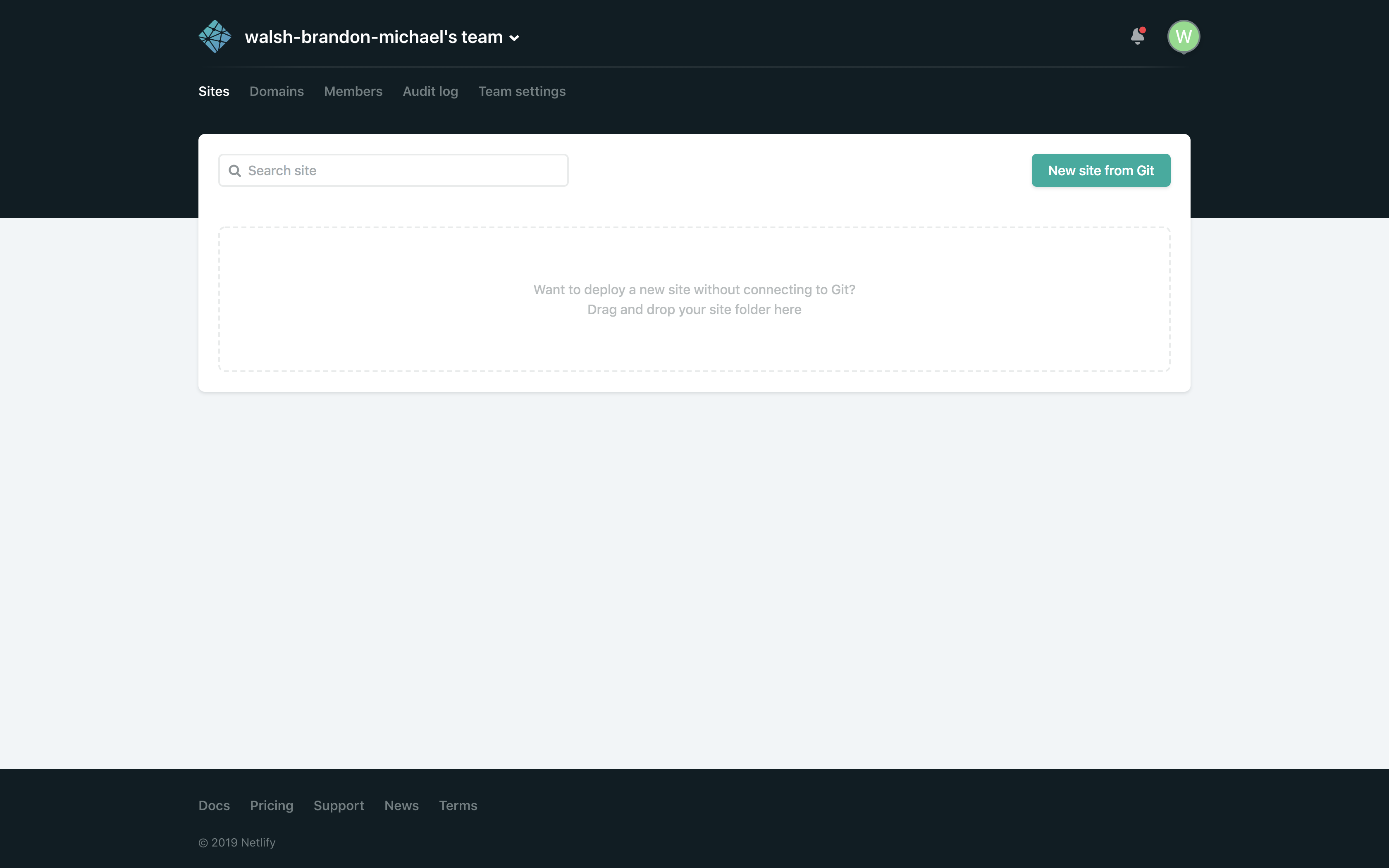

Sign up for an account on netlify.com and log in. You should see the following screen:

Screenshot of the Netlify dashboard

You will need to link your Netlify account and your GitHub account. You can do this by accessing your user settings by clicking on the avatar associated with your user name in the top right of the screen.

Screenshot of how to access netlify settings in top right of the dashboard

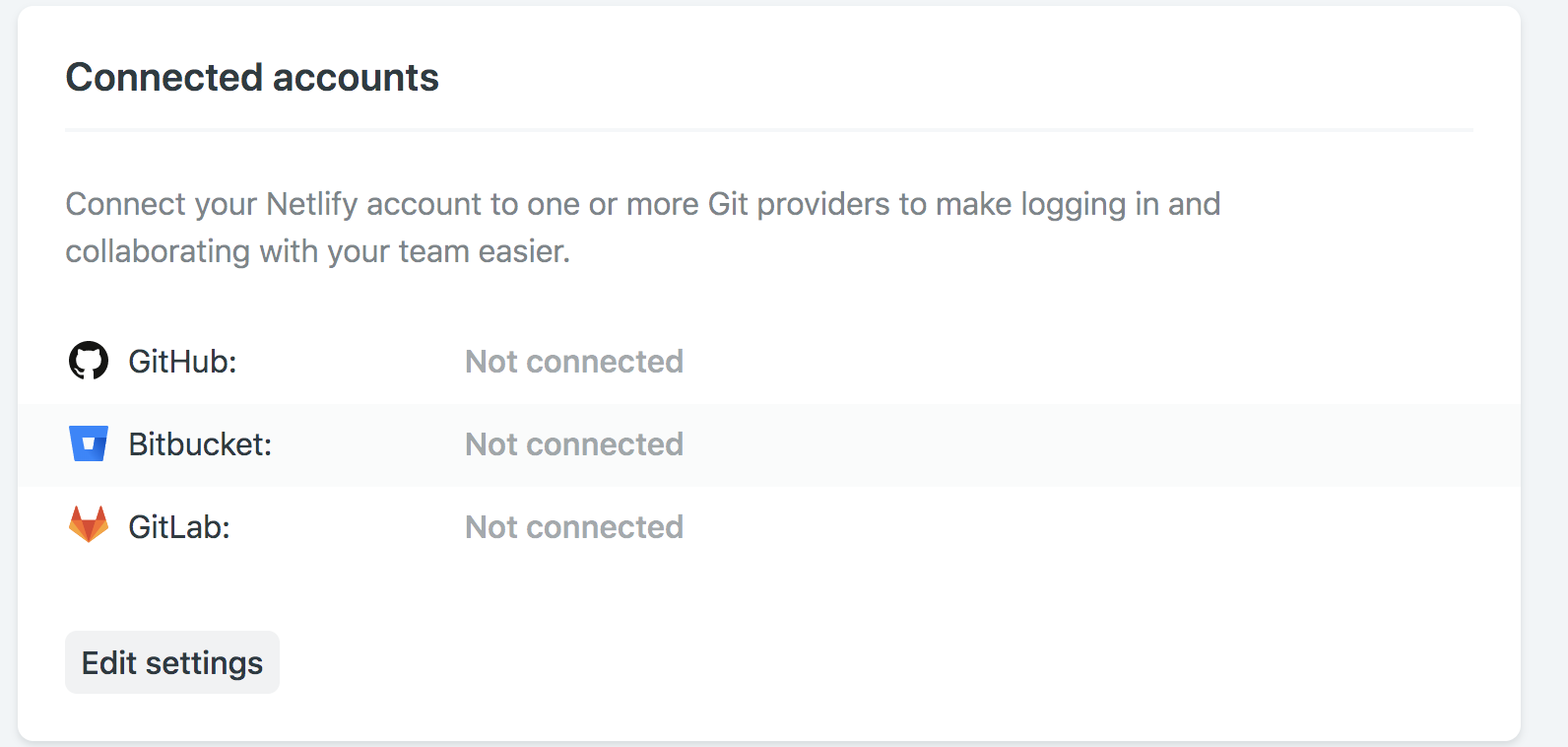

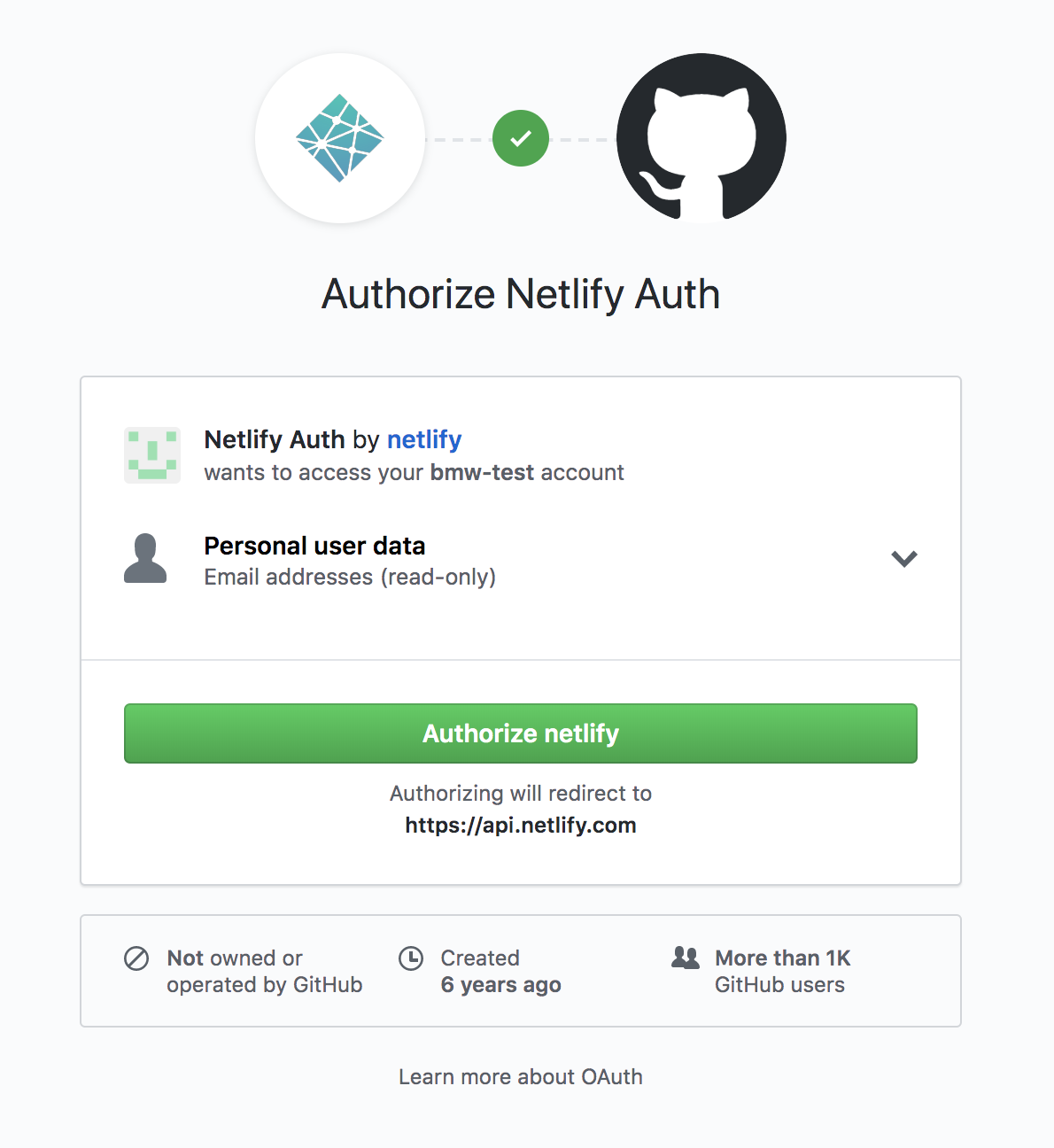

Within this interface, scroll down to the section titled “connected accounts,” click “edit settings”, and click “connect” next to GitHub. A dialog box should pop up asking you to log in for GitHub. After doing so, you’ll want to click “authorize” to allow Netlify to interact with the code that you’re publishing through GitHub.

Screenshot of authorization pop up for Netlify

After authorizing Netlify, return to the Netlify dashboard and select “New site from Git.” You’ll want to select “GitHub” on the page that it redirects you towards, and then select “Authorize” if another popup appears. The dialogue will ask whether you want to authorize Netlify for all apps or select a specific one. Either one is fine, but for the purposes of this lesson we will be specific and simply select the particular repository you created for this lesson. Select install after you’re done.

The “create a new site” Netlify window will shift slightly to offer new options. You’ll want to select your repository. Under “branch to deploy” select “gh-pages.” Netlify will automatically detect that you have a Jekyll site and fill in other settings under build command and publish directory for you.

Finally, click deploy. You should be all set now, and Netlify will be waiting for your use later in the lesson.

Set up your site for multiple authors

Out of the box Jekyll does not quite conform to some of the expectations you might have for a collaborative research environment. Given the scholarly use case imagined by this lesson, we need to customize the basic Jekyll set-up to better accommodate multiple authors working collaboratively. This section will set up your site to link a post’s author name to a page with biographical information and past posts by that author.

Note: throughout this section you can explore changes to your website by visiting https://scholarslab.github.io/CollabDemo (substituting scholarslab with whatever your GitHub username is and CollabDemo with whatever you’ve named your repository).

If you’ve done the previous lesson on Jekyll, you can use those skills in this section to edit repo files on your desktop and commit them using the GitHub Desktop app[^7]. If you’re not comfortable with this, please see the authoring and editing section later in this lesson where we explain how to create and edit files entirely on GitHub.com for collaborators who may prefer to do everything in the browser. Although that section focuses on creating and editing posts, the same steps apply for creating and editing any website files.

By default, Jekyll’s main piece of data is the post. You can tell Jekyll who the author of that post is, but, as far as Jekyll is concerned, that “author” is just a string of characters. If we want to give authors more robust identities, we’ll need to give Jekyll a sense of authors as a type of information. In Jekyll parlance, each of these distinct types of data is called a collection, and we need to do a few things to integrate them in our blogging environment. First, we’ll need to create the idea of an author collection. To do so, open _config.yml in a plain text editor and add these three lines at the end of it:

collections:

people:

output: true

Second, we’ll need to create some new authors for our site. Just as with our blog posts in their _posts folder, each author will live in its own file in its own folder. Let’s make a new folder in the repository called “_people”. Inside the _people folder, create two new files for the two authors of this lesson. We’ll title these files amanda-visconti.md and brandon-walsh.md. Next we’ll add content to each.

Inside amanda-visconti.md, add the following

---

name: Amanda Visconti

layout: author

---

Amanda Visconti is Managing Director of the Scholars' Lab at the University of Virginia Library.

Inside brandon-walsh.md, add the following:

---

name: Brandon Walsh

layout: author

---

Brandon Walsh is the Head of Student Programs in the Scholars' Lab at the University of Virginia Library.

Each author for the blog now exists as a piece of data in our Jekyll project. Note that the YAML header (the piece between three dashes at the top of each file) contains metadata about the collection. We can access these pieces of data in other parts of the project. The layout: key signals that each author’s page will draw upon the “author” layout, which doesn’t exist just yet. Let’s make it.

In the top level of your repo, create a new folder called “_layouts” and, inside it, create a new file called “author.md”. Inside author.md, insert the following content:

---

layout: default

---

<h2>{{ page.name }}</h2>

{{ content }}

This page creates the template for each individual author’s page through a mixture of items that will appear common to all author pages (like “Biography:”) and items that will be specific to particular author pages. The latter works by accessing the metadata fields for particular authors to find their name from the YAML header.

To make these pages accessible, we’ll want to create a page that lists all the site’s authors in one place. We’ll do that by making a new file called “writers.md” in the base of our repository and inserting these lines:

---

layout: page

title: Authors

---

All authors on this research project:

{% for person in site.people %}

* <a href="{{ site.baseurl }}{{ person.url }}">{{ person.name }}</a>

{% endfor %}

We’re just about done wiring things all together. Let’s make just a few more tweaks. For one, let’s edit the pages for individual authors to display a list of all the posts written by them. Open _layouts/author.md and add the following code underneath what’s already there:

<h2>Posts by {{ page.name }}:</h2>

<ul>

{% for post in site.posts %}

{% if post.author == page.name %}

<li><a href="{{ site.baseurl }}{{ post.url }}">{{ post.title }}</a></li>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

</ul>

_layouts/author.md should now look like:

---

layout: default

---

<h2>{{ page.name }}</h2>

{{ content }}

<h2>Posts by {{ page.name }}:</h2>

<ul>

{% for post in site.posts %}

{% if post.author == page.name %}

<li><a href="{{ site.baseurl }}{{ post.url }}">{{ post.title }}</a></li>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

</ul>

Now we’ll add author information to our existing posts; any future posts should include this info as well. Navigate to each existing post and add author: on its own line in the front matter, followed by the post author’s name. This name needs to be written exactly as it appears in the author bio file the site has for you (check the repo’s /_people folder/your-name.md next to its “name” YAML). If you want to change displayed name, first change the “name” field in /_people folder/their-name.md.

The YAML at the top of a post should now look like this:

---

layout: post

author: Amanda Visconti

title: "A Post about My Research"

date: 2016-11-12

---

Almost done! If you were to look at an individual post on your website, you would see that it already lists the author of the post. But if you were to try to click it, Jekyll won’t let you do so. Let’s connect that static string of characters listed on the top of each post to the author pages that we created. To do that, you’ll need to create another layout. Create a new file named post.md inside /_layouts. Inside it, add this text

---

layout: default

---

<article class="post" itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/BlogPosting">

<header class="post-header">

<h1 class="post-title" itemprop="name headline">{{ page.title | escape }}</h1>

<p class="post-meta"><time datetime="{{ page.date | date_to_xmlschema }}" itemprop="datePublished">{{ page.date | date: "%b %-d, %Y" }}</time>{% if page.author %} • <span itemprop="author" itemscope itemtype="http://schema.org/Person"><span itemprop="name">

{% for person in site.people %}

{% if person.name == page.author %}

<a href="{{ site.baseurl }}{{ person.url }}">{{ page.author }}</a>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

</span></span>{% endif %}</p>

</header>

<div class="post-content" itemprop="articleBody">

{{ content }}

</div>

</article>

That might seem like a lot, but we’ve actually only changed a few lines. By default, when you install Jekyll on your computer you are installing a lot of default files that it hides from your view but continues to use to build your site without your knowing. The result is that your repository will only show the files you actually are working with, but it can obscure what is actually going on under the hood. Minima is the default theme for Jekyll at the time of writing, which means that you’re working with a lot of files with decisions that have already been made for you by that theme. If you’re interested in seeing the default files for the minima theme, you can type bundle show minima from the command line. In this case, the lines we modified from the original theme are here:

{% for person in site.people %}

{% if person.name == page.author %}

<a href="{{ site.baseurl }}{{ person.url }}">{{ page.author }}</a>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

Before, the theme only listed the assigned author for the post. We’ve added a loop that essentially goes back to all the people on the site and, if it finds a name that matches the author of the post, it will link to that person’s author page.

Reviewer permissions

Our review process will rely on GitHub’s “pull request” (aka PR) system. Pull requests are just a way to ask that the changes you’ve made in your “branch” (copy of the website files) be “pulled” (moved) into another branch. In our case, we ask folks to make a copy of our website files, add or edit posts on that copy, then move those changes back into the default branch of the repo (which controls what visitors to your website see) once the changes are ready to integrate.

Our review adds two features to your publishing workflow. First, we’re adding the ability to run “checks”: a feature for your pull requests that can alert you to bugs in your new code or (as we’ll show in this lesson) give you a preview of what your changes will look like before they’re moved to the public website. Second, we’re adding the opportunity for review by making it easy to ping one of your collaborators to look over your changes, before moving them to the website. You can require this review if you or your collaborators are concerned about accidentally breaking the site or want everyone in your research team to sign off on writing about shared work, or you can make review optional, if folks only want to use it when desiring feedback on their writing before it goes public. Besides ensuring that that your content reaches your audience in the ways you intend, a workflow like this also helps to make the shared blog more truly collaborative by encouraging collective ownership over the material.

Caveat: This sets up a workflow involving pull requests that will ensure collaborative reviewing of your work before making it part of the official record. But it is still possible for a collaborator to accidentally push changes directly to the master branch and affect the main site by bypassing this process. In order to restrict who can push to a particular branch, you would need to follow GitHub’s instructions to create a GitHub “organization” (a team container which multiple repositories can live inside; e.g. Scholars’ Lab GitHub organization containing all the lab’s repos). You would then need to make this repository a part of a GitHub organization.

Our instructions assume:

- You created the repo, and thus automatically have the “admin” permission setting associated with your GitHub account.

- You are one of the site authors most comfortable with running the site, and therefore don’t need someone else to approve your changes before merging them.

- One or more other people will also blog on your site, and you want to prevent these collaborators from pushing content to the public site without your checking over and approving their changes (at least until they are more comfortable with the workflow).

Even if you’re the only person authoring on your site, using branches and pull requests as discussed in this lesson can help you keep different chunks of work that are proceeding at different paces separate (e.g. if you start implementing a new homepage layout, but then want to publish a new blog post while the new homepage layout is all messed up and in-progress, putting these two sets of work in separate branches lets you publish the post with the old layout). Also, using branches lets you run Netlify (also discussed below) to see how your changes look before making them public, without needing to be comfortable with using the command line to run a local version of the site. Admin permissions mean that you won’t need to wait for someone else to review your pull request before merging it (i.e. making it appear on the live website), although you can always request and wait for review if you’re interested in feedback.

Don’t forget to substitute https://github.com/your-username/your-repo-name for https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo in these instructions. To set up your site for our review process:

Each person besides you who will write on the site should create a user account on GitHub.com, if they don’t already have one. They’ll need to share their username with you (or someone else with admin permission).

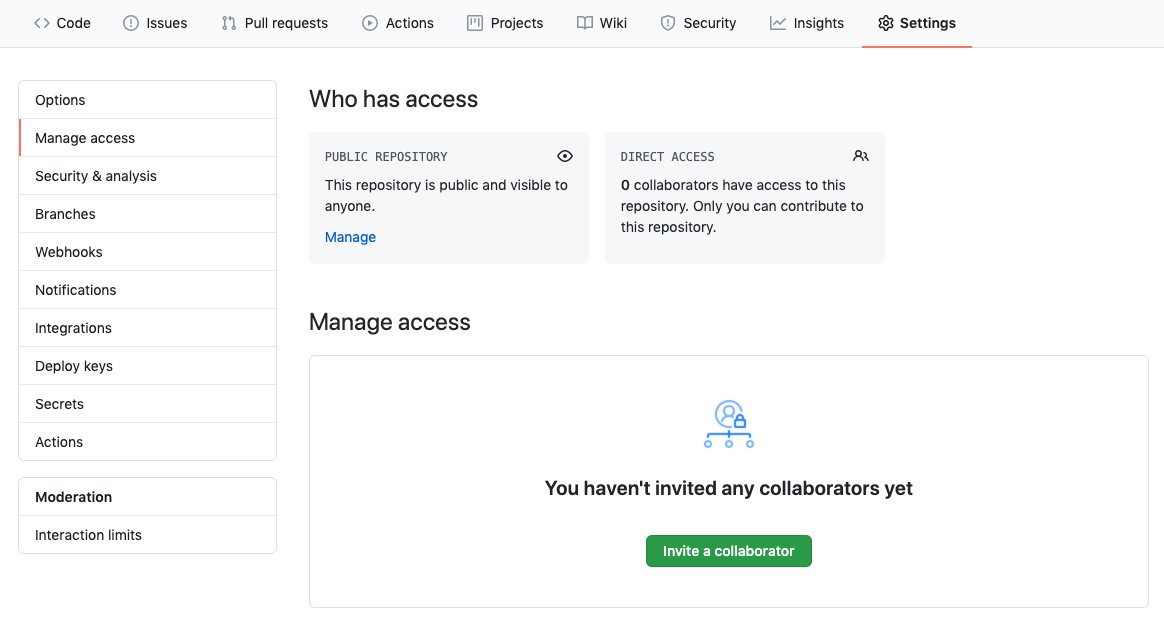

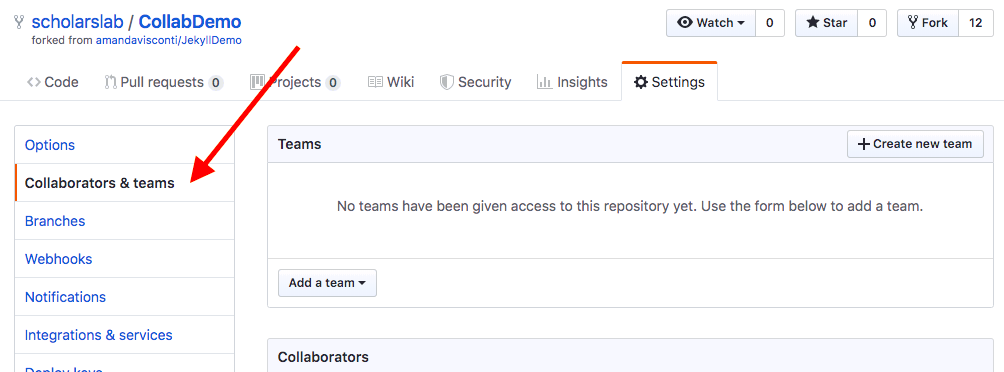

Your repo page (e.g. https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo) has horizontal row of links just below the name of the repo. Click on the “settings” link, then click on “Collaborators & teams” (possibly displaying just as “Collaborators”) in the lefthand menu.

Screenshot of the settings tab in the horizontal row of links just below the name of the repo

Screenshot of Collaborators & Teams link in the settings page lefthand menu

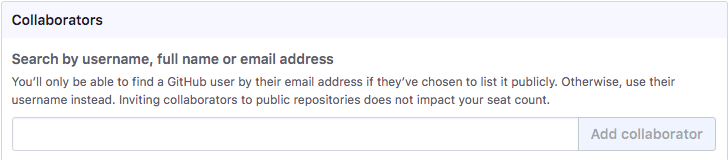

You’ll see a section for “teams”, followed by a section for “collaborators”. Inside the “collaborators” section, use the “Search by username, full name or email address” field to find the GitHub username(s) of folks who will share the blog, then click the “add collaborator” button to give them access to doing things with the repo.

Screenshot of the field where you grant collaborators access to the repo

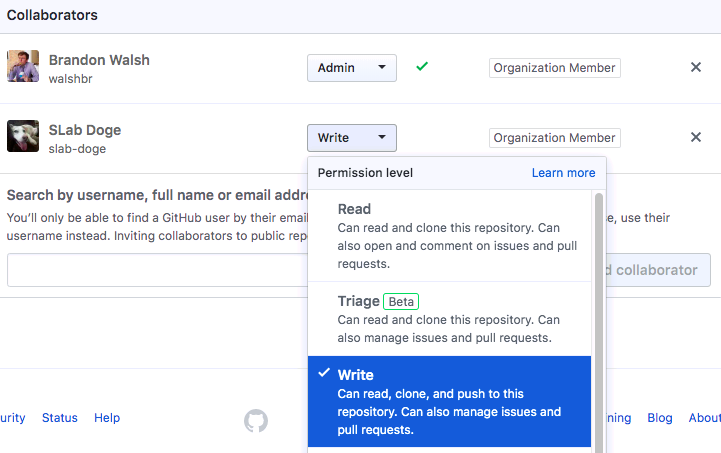

The collaborator(s) you’ve added will now be listed in the “collaborators” section. There will be a dropdown menu to the right of each username.

In our case study, we want new bloggers to need to follow our review process before they can publish to the public website; we need to give them a non-admin role to make that happen, so we use this dropdown to change each of these folks’ permissions to “write”.

To give someone full access to the repo (the same access you have, including the ability to move changes to the public website without review or notification of others) you would make sure that dropdown says “admin”.

In the screenshot below, you can see we’ve granted Jekyll Power User Brandon Walsh the “admin” role, but our demo account SLab Doge the “writer” role (she’s a good dog, but we don’t trust her to not break the site!).

Screenshot showing how to grant collaborators different levels of access to your site

Click on “Integrations & services” in the upper-lefthand menu. Under “Installed GitHub Apps”, Netlify should be listed; click on the “configure” button to the right of Netlify.

Scroll down to the “Repository access” section. Either one of these options is fine: the radio button next to “All repositories” is selected; or if you have other repositories you’re not sure you want Netlify to run on, select the radio button next to “Only select repositories”. For the latter choice, your repository should appear in the list immediately below; if it does not, use the “Select repositories” dropdown menu to add your /CollabDemo repo. Click the green “save” button.

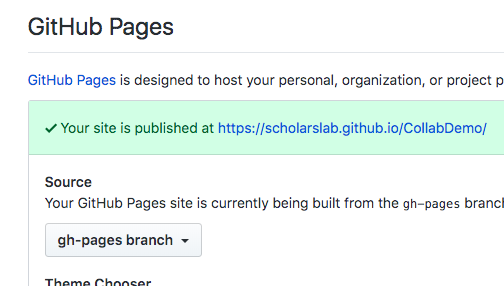

Now we’re going to verify the name of the default branch that GitHub Pages publishes as your website. This should be “gh-pages” based on how we had you set up your repository for Netlify, but we’ll show you how to check.

Click on “Options” in the upper-lefthand menu, and scroll down to the “GitHub Pages” section to look at what the dropdown under “Source” says; what you see should look similar to the screenshot below, but might contain a different branch name in the dropdown. Remember whatever branch name is listed here for use in the next step.

Screenshot showing how to check the name of the repo branch that publishes to GitHub Pages

In the upper-lefthand menu, click on “Branches”. Scroll past the “Default branch” section to the “Branch protection rules” section. Click the “add rule” button on the far right of “Branch protection rules”.

Under “Branch name pattern”, type the name of your repo branch that’s being published by GitHub Pages as a website. If you’re following this lesson closely, this should be “gh-pages”.

Scroll down to the “Rule settings” section and check the checkbox next to “Require pull request reviews before merging”. More information will appear just below this text.

In the dropdown, choose “1”, which will make the dropdown display “Required approving reviews: 1”.

This means that when folks without the “admin” role are ready to publish something, one other person on your team needs to press a button to allow that to happen (with the idea being they’ll first look over the new post to give feedback and/or fix things such as broken Markdown formatting).

Check the checkbox next to “Dismiss stale pull request approvals when new commits are pushed”.

If someone asks for their blog post to be reviewed, but then makes some changes to that post before the reviewer has a chance to look at it, this means the reviewer will be pointed to look at just the latest version of the post up for review.

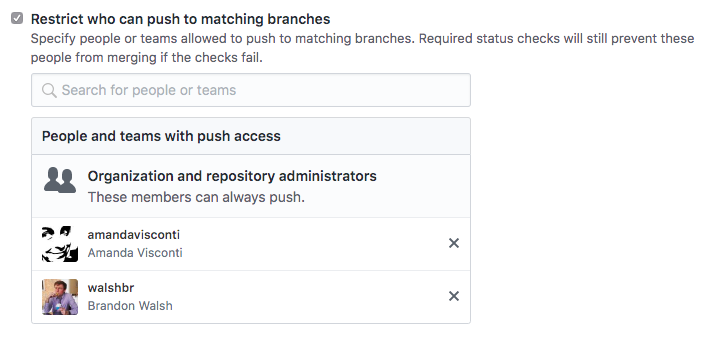

An additional option, “Restrict who can push to matching branches”, will only be available to place a checkmark by if you’ve created an organization this repo lives inside, as discussed in the third paragraph of this “review permissions” section.

Checking this rule limits who is allowed to move changes such as new blog posts to the branch that publishes your website. In our setup, folks with the “admin” role can already move changes to your public website without needing someone else to approve these first; “admin” folks are also the people who are allowed to approve other authors’ posts (i.e. make them appear on the public website). You can add collaborator usernames using this field if/when those folks are comfortable with being able to push content to the public website without someone else’s approval.

“Admin” folks and others you add here can still make use of the review system we’ll describe later in this lesson; they just have the additional option of not waiting for a collaborator to approve their changes, if they’re confident they understand how to update the website. Even folks who always want feedback on a new blog post may appreciate being able to forgo the approval process when making other small, simple changes to the website, such as updating an author’s name.

In the screenshot below, you can see Brandon and Amanda both override the restriction on who can push to the public website, but SLab Doge cannot (and thus does not appear in this list of usernames):

Screenshot showing how to restrict some collaborators to following the review process

Click the green “Save changes” button at the bottom-left of the page.

You’ll want the site to let folks know if someone on your team requests a reviewer. Each reviewer can receive these notifications by visiting https://github.com/settings/profile and clicking on “notifications” in the lefthand menu. Scroll down to the “email notifications” section, make sure the email where you want to receive notifications is entered correctly, and tick the checkbox next to “Pull Request reviews”.

Your site setup is now complete! Next we’ll cover authoring and editing on your website, including how the review process we just set up works.

Authoring and Editing

In our workflow, there are two parts to authoring on or editing your website:

1. Create a new “branch” and create/edit your post/page there. A branch is a copy of the website’s files, where you can create new posts or change existing pages without these changes showing up on the public website until you’re ready for them to be seen. Working in a branch also allows multiple people to be working on different posts (or changes to the site; GitHub doesn’t differentiate in how it handles your writing a post vs. coding a new technical functionality) at the same time. A repo can (and often does) have multiple branches at any one time.

2. “Merge” (move) your work back to the repo’s default branch, which makes your work show up on the website. The default branch is the copy of the website files from which we’ve told GitHub Pages to build our website. “Merging” means moving any changes/additions you’ve made in your new branch to another branch (in our case, back to the gh-pages branch from which the site runs).

If you forget what any of these technical terms mean, visit our glossary for a reminder.

The previous Jekyll lesson had a section on how to create and edit posts and pages, so we suggest reviewing that lesson for a general introduction to blogging in Jekyll[^8]. In what follows, we describe the changes to those instructions that will be required for your site to function better as a collaborative blog. The key differences from the last lesson are:

- the use of branches

- authoring and editing on the GitHub.com website (i.e. in your browser) rather than locally (in your computer’s file system)

- several changes to post front matter

- rather than committing directly to your website’s default repo branch, we’ll show you a different method for review and publishing

Create a branch

Our workflow has authors create a new branch before starting new work such as drafting a blog post, editing an existing webpage, or other code changes.

Visit the main page for your website’s “repo” (repository). We’ll use our demo repo, https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo, as our example. A repo is like a folder of code, and this repo in particular is the place on GitHub.com where we store all the files that make up the CollabDemo website (https://scholarslab.github.io/CollabDemo/).

When you create a new repo, it will start with a single, “default” branch, meaning the repo is the same thing as the default branch. We create branches (copies of the default branch code) so you can make changes to the website (draft a new blog post, edit a page, play with the site’s visual design…) without affecting how the live website looks (your changes won’t appear where the world could hypothetically see them, until you’re ready!) and without conflicting with other folks’ simultaneous work on the site. To state this another way: the “default” branch is the code producing the website you see, and any other branches you create are spaces where you can draft and tinker without affecting what the public sees on your website.

As discussed above, the default branch you’re in here should be called gh-pages. When you visit https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo, you’ll see the default branch of that repo is also named “gh-pages”. This branch contains the code powering the site publicly visible at https://scholarslab.github.io/CollabDemo].

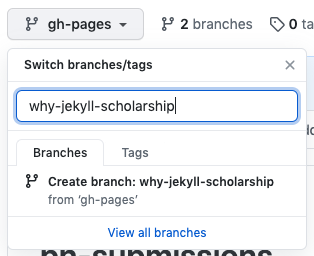

In the mid-left of your browser window, click on the grey “Branch: 🔽” button.

A dropdown appears. In the empty text field (it says “Find or create a branch…” in light grey text in the text field’s background), write a very short descriptive name for your new branch. In our example, we’re creating a blog post about using Jekyll to support scholarly blogging, so we’ve named our branch “why-jekyll-blogging”:

Screenshot showing how to create and name new branch

If your branch name has spaces in it, these will be replaced by hyphens. It’s best to keep these names short (1-4 words, easy to see without the text getting cut off by the dropdown menu’s width) and descriptive (so folks have an idea what the work happening in the branch is, and you can remember if you drop the work and come back to it later on). You wouldn’t want to name your branch “new-post” because other folks might also be working on new posts in other branches, and your branch name might confuse them. It doesn’t matter too much what you name your branch, as long as you can recognize the branch name when you see it.

When you’re creating a branch, please substitute your chosen branch name where we use why-jekyll-scholarhip in this lesson (remember to also change GitHub.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo to match your own username and repo name).

Once you’ve finished typing your new branch name in the field, you’ll see a blue rectangle just below with the words “Create branch: why-jekyll-scholarship”. Click anywhere on that blue rectangle.

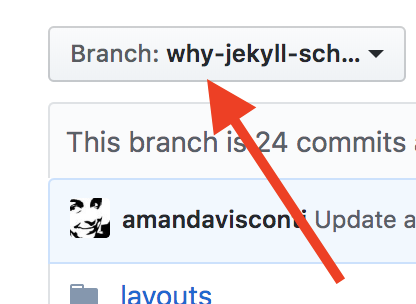

When you create a new branch, GitHub automatically moves you there so that any changes you make affect the new branch, rather than the default branch. You can tell what branch you’re working in by looking at the branch dropdown to verify that we’re now in the branch why-jekyll-scholarship. This is that same grey button in the mid-left of the page we clicked before, when we created a new branch. In the screenshot below, you can see that our branch has changed from gh-pages to why-jekyll-scholarship:

Screenshot showing we’ve switched into our new branch

You can also look at the address bar; the URL will have switched from https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo to https://github.com/scholarslab/CollabDemo/tree/why-jekyll-scholarship.

Now you are on a new branch (a parallel universe of sorts!) where you can work without affecting the repo that determines what’s on your website (e.g. you won’t see half-written blog posts appear on your site).

Authoring and editing on GitHub.com

The previous Jekyll lesson covers how to use Markdown and YAML to write a post or alter a page’s content and front matter, so we won’t duplicate that here. We will cover several changes from that lesson: how to create, commit, and edit a post on GitHub.com (rather than locally); changes to post front matter to support a collaborative website; and ways to check how your post appears from GitHub.com (i.e. when you’re not running your website locally).

Create a new post

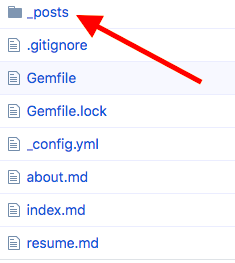

You should still be in the branch you created to contain your in-progress work.

In the repo’s list of files, click on the “_posts” link to move into where the site’s posts are stored.

Screenshot of the posts folder you should navigate into

Click on the “Create new file” button in the mid-upper righthand of the page.

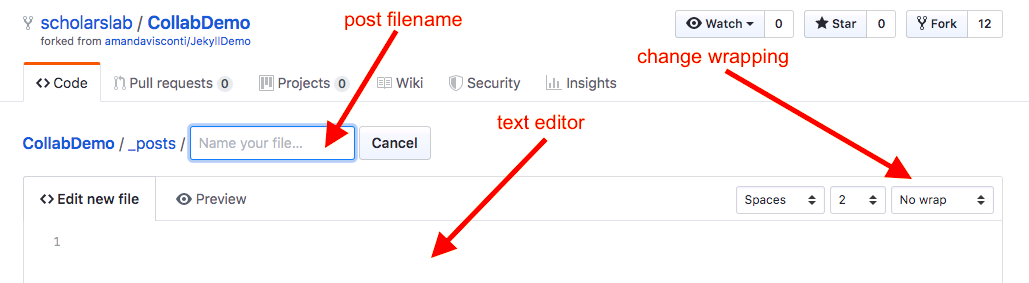

Screenshot of the new post being created in GitHub’s text editor

You are now in a text editor where you can create your post.

You should fill in the “Name your file” field with a filename matching the following format:

- the publication date you wanted associated with the post (formatted as

YYYY-MM-DD) connected by a hyphen to - a “slug” for the post (short descriptive phrase; as with branch naming, it’s best to keep the slug text fairly short and use important keywords in it, and you must use hyphens instead of spaces)

- followed by

.mdor.markdown(both are acceptable as the markdown file ending)

For example, one of our example posts’ filenames is 2016-02-29-a-post-about-my-research.md. If it were an actual post with content, it could have a more descriptive filename like 2016-02-29-daily-digital-humanities-personal-research-practices.md.

Screenshot of the text editor page

Use the text editor to enter your front matter. Note that this post metadata will be different from how it looked in the previous Jekyll lesson; see below for what should change.

Note you can click on the “No wrap” dropdown in the upper-right to select “Soft wrap”, which will make your writing experience more pleasant by wrapping text to continue to the next line when it reaches the right margin, instead of extending right forever until you hit return/move to a new line.

Type some text into the text field (e.g. a sentence) so that you can test out the next steps.

Committing, AKA saving your work

GitHub is very forgiving; the whole magic of using git to store and track changes in many versions of text (e.g. code) over time is that you can always roll things back to how they were. The system for reviewing and merging writing described in this lesson makes it so folks not comfortable with GitHub can’t delete other folks’ work or break the website. And even if you could, using git versioning means we can easily roll back any changes you make to how the site previously looked/functioned.

The one way GitHub is not forgiving is that you can lose text you’re currently drafting in the GitHub.com text editor, if your tab/browser/computer closes/restarts when you’ve added new text to the file, but not committed it yet.

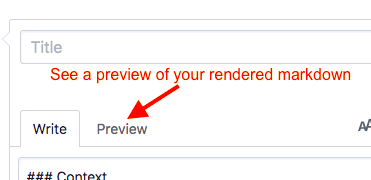

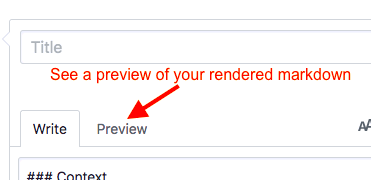

Commit (aka save) about as often as you’d save a word document. Or, draft your text elsewhere (e.g. in a GoogleDoc), then paste the final text into the GitHub text editor just when you’re ready to publish it. You can always switch to the “Preview changes” tab to see how your writing formatting looks (especially helpful if you’re new to using Markdown formatting):

Screenshot of where the text editor’s preview button is found

Where the previous lesson had you use the GitHub Desktop app to commit and merge, we’ll instead use the GitHub.com interface. This lets authors unfamiliar or uncomfortable with the command line or running a site locally instead do everything from GitHub.com.

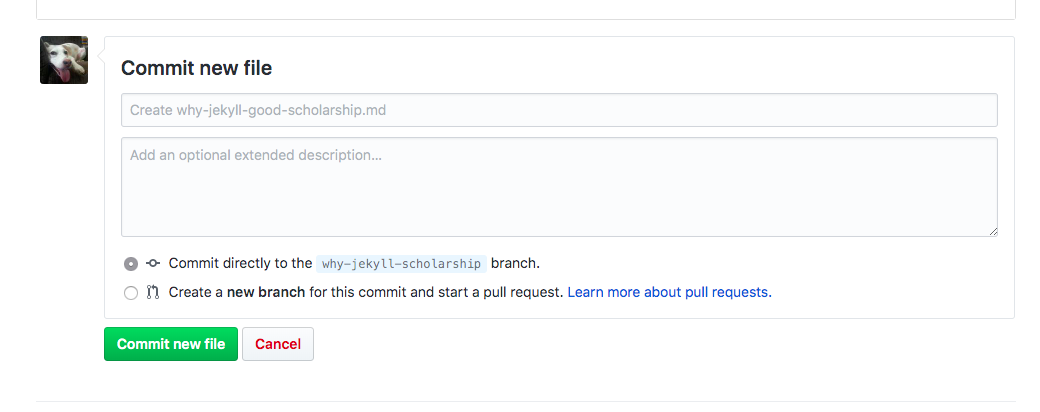

To commit (aka save) your work, scroll down to the bottom of the text editor page.

The commit area is under the text editor area

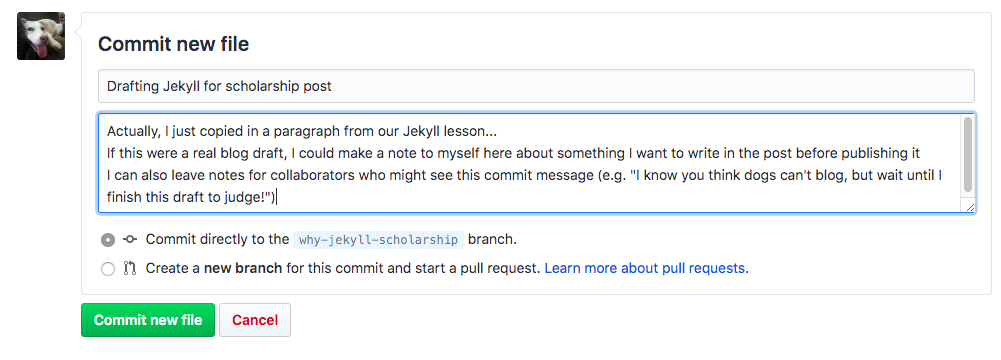

The first text field is a place to write a short description to remind you and inform others about what changes you made to the code (in our case, to your new blog post).

The field will make you stop typing if you attempt to go over the character limit. If you’re writing or editing a new blog post, you can opt to write nothing in this field; that accepts the grey default text already in the field (“Create why-jekyll-good-scholarship.md” in the screenshot) as your commit message. If you’re making changes to the site other than blogging, it’s probably good to update this field to a short description of what your code changes/accomplishes (e.g. “Fixed missing author link”).

The larger text box (“Add an optional extended description…”) gives you more space to explain what the code you’re committing (saving) does.

If you were making changes to the website’s code that others needed to understand, adding text here to explain your changes would be useful, but you can ignore it when you’re authoring a new blog post. When changing code or editing existing webpages, writing a longer description in this area helps your team easily see who made what changes. These messages will be part of the public record of the repo on GitHub, so don’t write anything you wouldn’t want seen publicly.

Screenshot of example commit message

Leave the radio buttons as-is (i.e. “Commit directly to the [your branch name] branch.” should be selected.

Click the green “Commit new file” button to finish saving your work.

Adjustments to front matter

You’ll need to make four changes to how the previous lesson directed you to write the front matter of a blog post:

- Add the “author” field (e.g. “author: Amanda Visconti”)

- Remove the hour, minute, and second info from the “date” YAML (we don’t find this useful to track and it cause timezone weirdness to happen when publishing)

- Remove the “categories” YAML field as these lessons don’t cover using it

- The post filename does not need to contain a date (e.g. “why-jekyll-good-scholarship.md”)

Our front matter should look like:

---

layout: post

author: Amanda Visconti

title: "A Post about My Research"

date: 2016-11-12

---

Author should contain the post author’s name, exactly as written in the author bio file the site has for you (check the repo’s /_people folder/your-name.md next to its “name” YAML). To change how the site display’s an author’s name next to their posts, first change the “name” field in /_people folder/their-name.md.

Date should contain the date the post is to be listed as written, using the YYYY-MM-DD format, e.g. 2018-10-17. Note that the year comes first; hyphens separate the year, month, and day. This date field will affect the URL and metadata for our post and show when it was written. In our current setup, though, the field does not have anything to do when the post actually goes live on our website. This publication happens when the site itself builds, so a post might live on your computer for days before being released to the world, or you might retroactively publish a post dated in the past if you so choose.

Make a habit of putting quotation marks around your title; this keeps the site from breaking when your title includes unexpected characters like colons.

Edit existing content

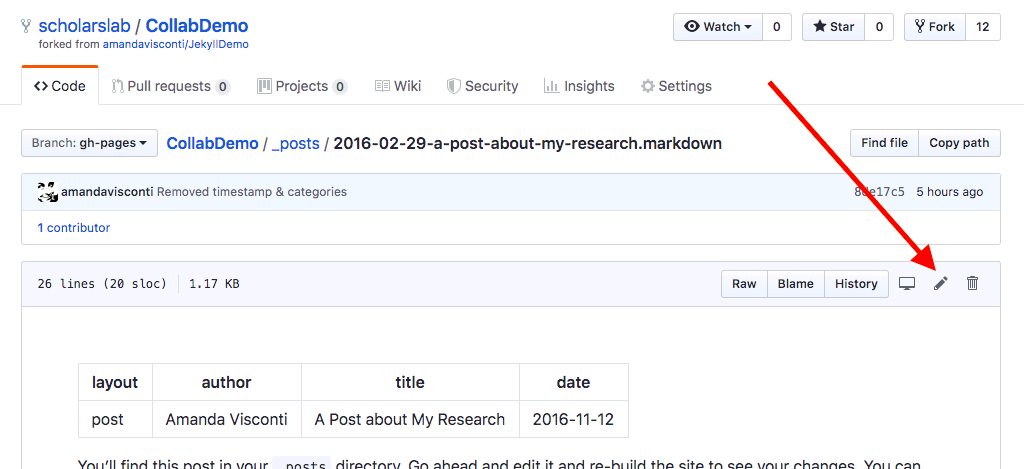

To continue to edit your blog post after commiting, locate the post file (in the /_posts folder) and click on its link. Then, click on the small pencil icon to the righthand middle of the page (if you hover your cursor over the icon, you’ll see the words “edit this file” appear). This brings you to a text editor, after which you follow the same steps to save your changes as you did when creating a new file.

Screenshot of where to find the edit icon

Checking how your post appears

Although this isn’t the same as seeing what your post will look like when published to your website, you can either:

- look at the GitHub repo version of your post to see whether your Markdown formatting looks right (click on the post file link inside the _posts folder and scroll down to see your post)

- use the “preview post” option, or

Screenshot of how to preview a post

To see what your post looks like on the final website (i.e. incorporating any special design or functionality), you’ll either need to refer to the previous Jekyll lesson to learn to run your site locally, or wait until you’re ready to publish. (The Netlify tool we installed during setup lets you see what your webpage will look like when you’re moving your page to the live site, but not when you’re still drafting.)

Reviewing and Publishing

When you’re ready to publish your work, you’ll initiate a “pull request” and have your content “merged” into the public website by a reviewer, as described below.

Create a pull request

Our very first step was creating a new branch to do this work in, so that our work happens separately from other changes folks might want to make to the site at the same time. Now you’ve committed some change to our code: either creating a new post or page file, or editing an existing one. In this final step, we’ll incorporate your work back into the default branch, so your changes show up on our live website.

Some terminology:

- Merging: Taking two sets of code (that already have some shared code/text between them, e.g. our default branch and the duplicated then altered branch we created), and combining these into one set of updated code.

- Our workflow for posts and pages is pretty straightforward: we duplicated the default branch of our website code, made some changes to the code in a separate branch, and now we’re going to move your changes into the default branch.

- For repos where multiple people are changing the code at any time, sometimes working from branches of the code duplicated when the repo was in different states of progress, this is a much more complicated process.

- Pull request, aka PR: Asking that the changes you’ve made in your branch be “pulled” (moved) into the default branch.

- Our repo’s pull request process runs a “check” or “test” on your code: Netlify lets you take a peek at how your changes will look on the website, before we actually publish those changes for the world to see.

- Review: For our repo, making a pull request notifies other SLab folks that someone’s making a change to our website, allowing the opportunity for feedback on your work.

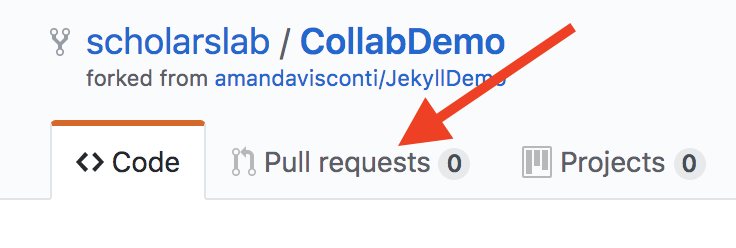

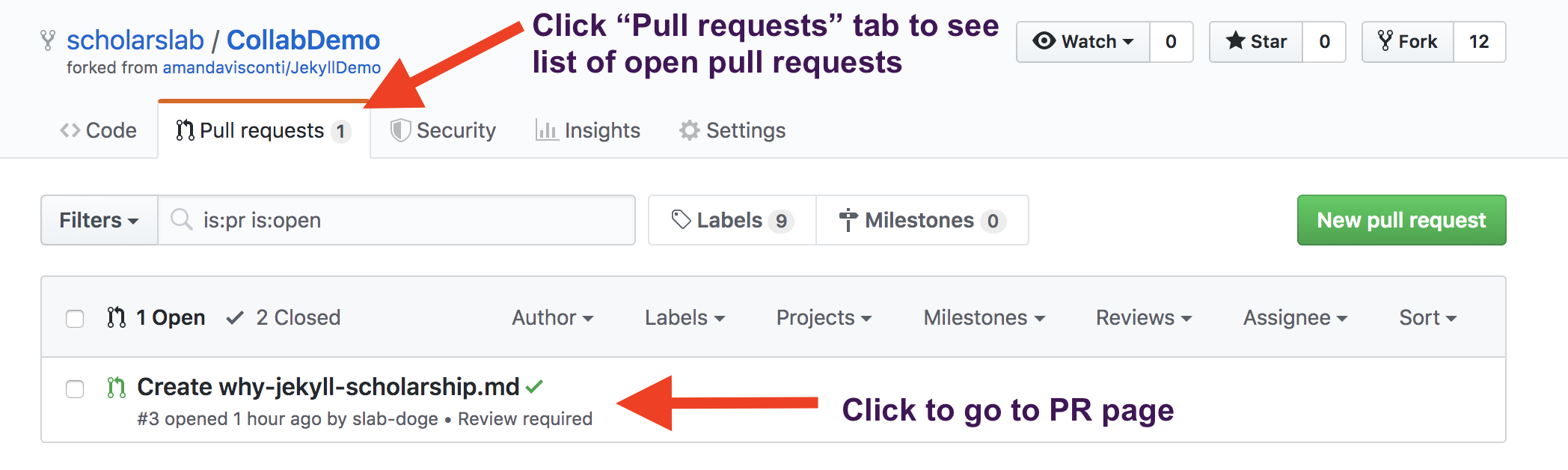

Click the “Pull requests” tab in the upper-left of your screen.

Any pull requests that are in-progress (undergoing or awaiting review) will also be listed here.

Screenshot of the pull requests tab

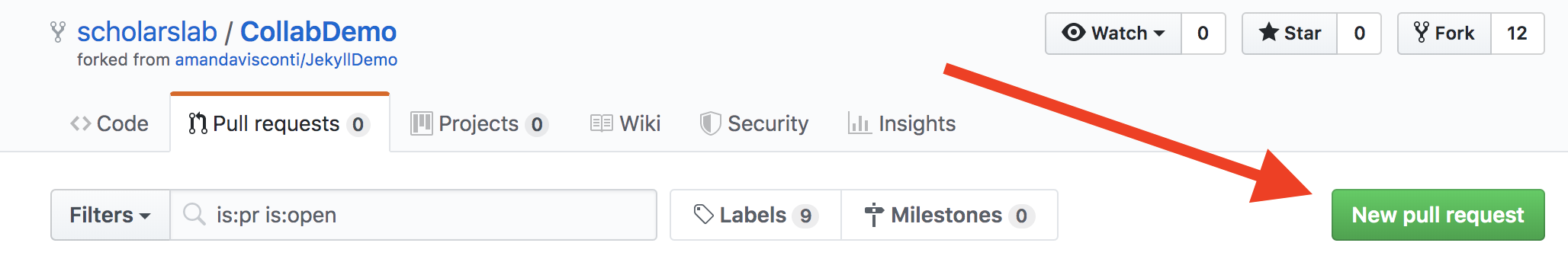

Click on the green “New pull request” button on the page’s upper-right.

Screenshot of the ‘New pull request’ button

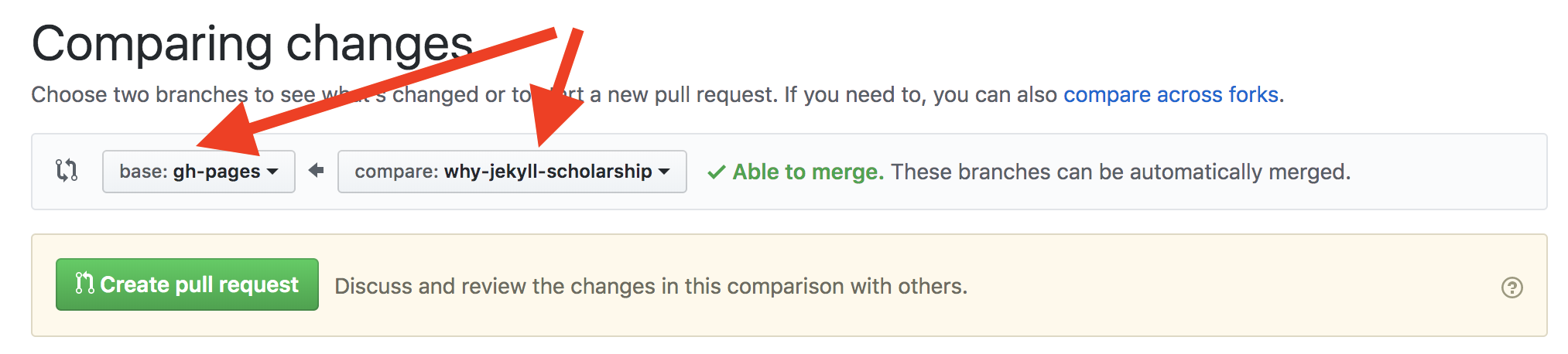

You’re now on the “comparing changes” page, where you can tell GitHub you want to look at the differences between the code in your branch and the code running the website.

The page displays dropdown fields to indicate the branch against which you’re comparing your own work. In most cases, this will also be the branch you plan to eventually merge your new work into.

Screenshot showing interface indicating we’re comparing our work branch with the website branch

Check that the correct branches are selected.

“Base” should contain the branch that runs your website (see the steps above on verifying which is your default branch if you’re not sure) where you want to move your post, and “compare” should contain the branch where you created your post (or made other changes to the website). In our example, “gh-pages” is the default branch that our website runs off, and “why-jekyll-scholarship” is the branch containing a new blog post.

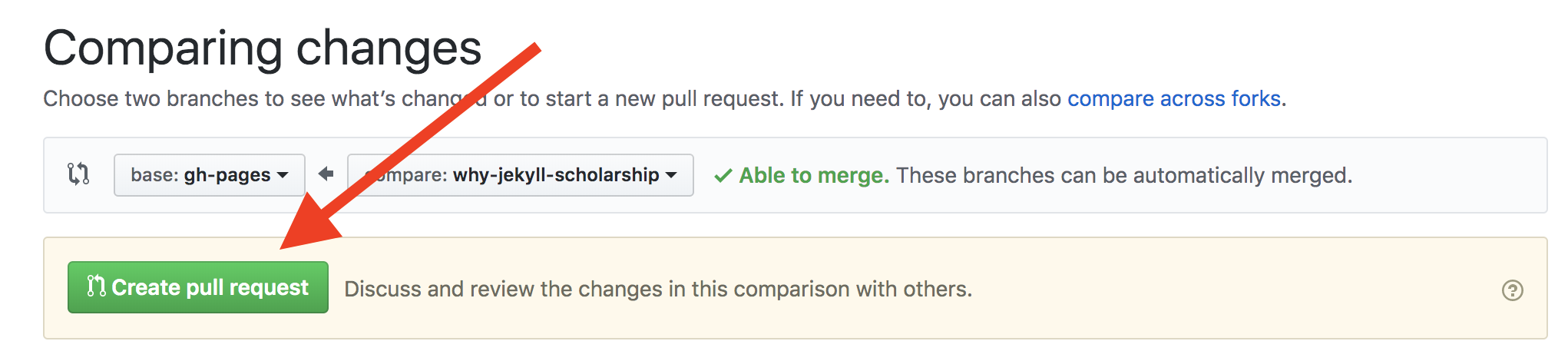

Click on the green “Create new pull request” button on the left.

Screenshot of the button for creating a new pull request

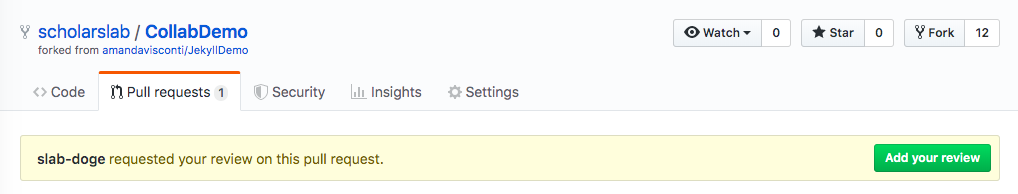

There’s a section labeled “Reviewers” under the righthand menu; click on the word “reviewers” to see a dropdown menu of folks associated with your repo who you could ask to review your work (added using the reviewer permissions steps). You’ll want to tag someone to review your work who has administrative permissions on your repository. This will notify the site authors who are comfortable with Jekyll (i.e. folks with “admin” privileges) that you’re making a change (e.g. adding a blog post) to the website.

If you’re not an admin, your work is now done: you’re just waiting for someone with admin privileges to briefly review your changes, using the steps in “Merging as an admin” below to check for anything that might break part of the site (highly unlikely with a blog post, more likely with changes to other repo code). Then, they’ll push your content to the live website. If you’d like a glimpse of what the website will look like when your changes are merged, the next section (“Merging as an admin”) will show you how to use Netlify to do this.

Merging as an admin

If you’re the one setting up your GitHub and Jekyll combination, you already have admin permissions for your repository. If not, you’ll need to contact the owner of the repository to give you access using steps 1-4 in the Reviewer Permissions section before being able to follow the steps below to merge collaborators’ changes.

Administrator permissions mean that you don’t need to wait for someone else to review your pull request before merging it (i.e. making it appear on the live website); you have the option of following this step below to skip review. If you wish, you can always request and wait for a review if you have any concerns about your code or wish for feedback on a post before publication. The following instructions cover how to review and merge a collaborator’s changes.

After someone has used the steps above to create a pull request:

If you hear a PR needs review via a GitHub email notification, that email will contain a link to the PR page. If someone doesn’t provide a link but tells you they have a PR needing review, you can find the PR page by clicking the “Pull requests” tab in the horizontal menu across the top of the repository, and then click on the PR you want to review in the list that appears:

Screenshot of locating the list of open PRs

On a PR page, you’ll see any comments the PR author left to describe the work you’ll be reviewing, followed by a list of any commits that author made while working on their branch.

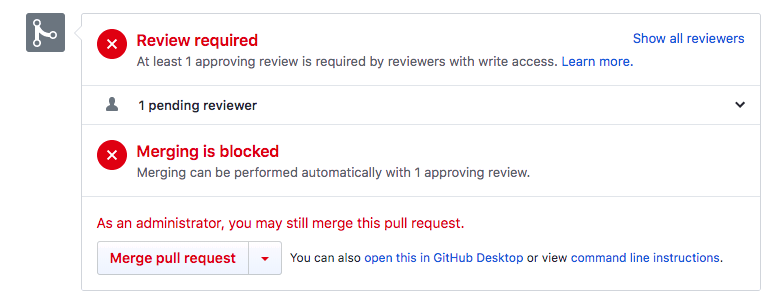

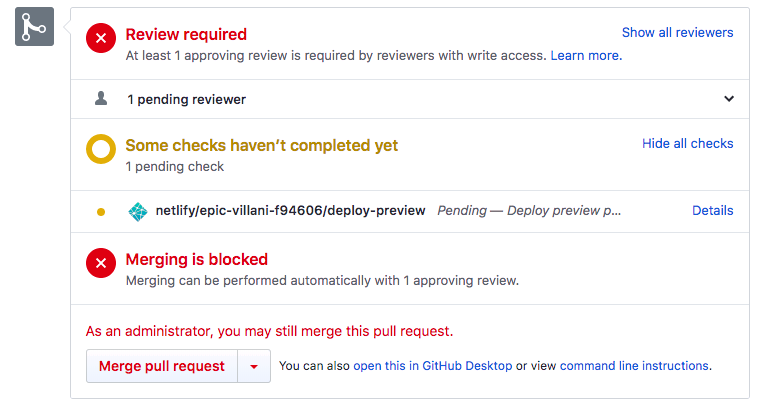

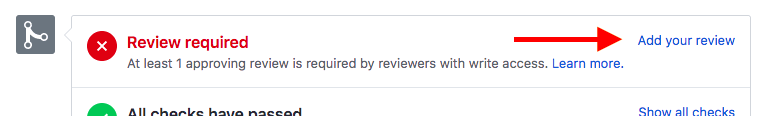

Scroll down until you see the “Review required” section and to see the status of the Netlify checks. You’ll need to wait until these checks have completed running.

If the PR was just created, it may take up to 30 seconds for the checks to appear, so if you just see something like the screenshot below, wait a moment:

Screenshot of the PR before the checks start running

When the checks start running, you’ll see a yellow circle next to the message “Some checks haven’t completed yet”.

Screenshot of the PR when the checks start running

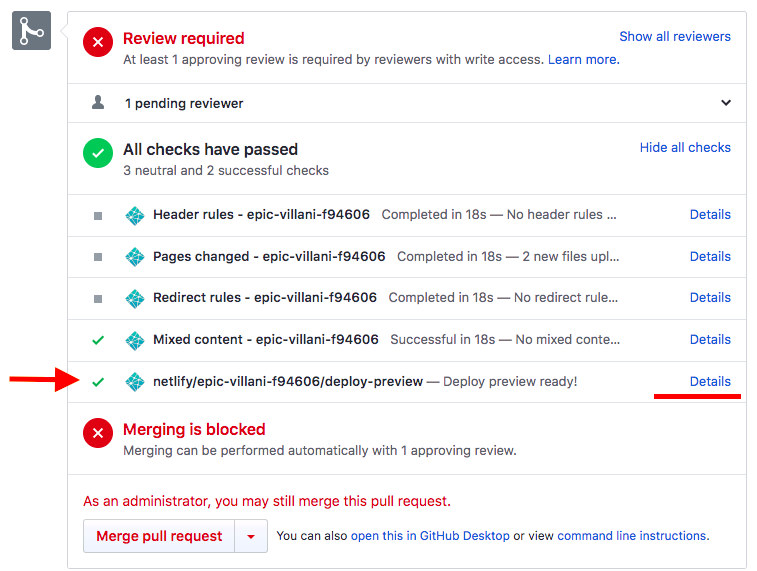

When the checks have finished running, you’ll see a green circle with a white checkmark inside it next to the words “All checks have passed”, followed by a bullet list (if you don’t see a bullet list, click on the “show all checks” link to the right).

Find the list item that says “netlify/” followed by some gibberish and then by “Deploy preview ready!” Right-click on the link to its right that says “Details” to open a new tab, which will show you what your site will look like after you merge the PR’s changes.

Screenshot of how to view the Netlify preview

Three possible next steps, depending on how the preview looks and how your review of the post goes:

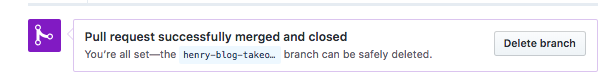

Option #1: If the preview looks good to you, you can click on the “Merge pull request” button in the bottom left of the section. Click the checkbox next to the “Use your administrator privileges to merge this pull request” message that appears, then click the “Confirm merge” button, followed by the “delete branch” button that will appear to the right. (Getting rid of branches once we’re done with them helps us keep the repo clean, as we may have multiple branches open at one time that are seeing active work.)

Screenshot showing deleting branch after PR

Option #2: If the preview doesn’t look right to you, you can leave a review in two ways.

If the PR author added your username to the list of requested reviewers (using the “reviewers” option at the upper-right of the page), you can scroll to the top of the page to see a yellow rectangle stating “[username] requested your review on this pull request”. Click on the green “add your review” button to the right of this message.

Screenshot showing to add a requested review

If the PR author did not add your username to the list of requested reviewers, you can still leave a review by looking at the top of the “review required” section and clicking the “add your review” link in the section’s upper-right.

Screenshot showing to add a review

A popup will appear where you can leave a comment; choose one of the three radio buttons to let the author know whether they need to make changes before re-submitting for review. Click the green “submit review” button in the lower-left of the popup.

Option #3: If you or the author want to edit the post further before publishing it, visit the post and edit it using the editing steps discussed above. The PR page’s list of commits will update to contain any subsequent commits, and will re-run the Netlify checks after each of these commits. You can follow the process above once you’re satisfied with your changes.

You’ve successfully merged your changes! You’ll need to wait from 1-10 minutes to see your work appear on the updated live website.

Drawbacks and Limitations

This lesson has been deliberately scoped down to be bare bones: it introduces how to develop a publication workflow and setups for structuring a collaborative writing environment via Jekyll, but leaves the environment itself fairly sparse. Robust content manage systems often contain a number of features to facilitate a collaborative blogging ecosystem. Think about all the things you might take for granted when browsing a community blog:

- posts are tagged with particular keywords

- these tags allow you to easily browse all posts sharing common content

- posts can be sorted and searched by date or author

While all of these features can be implemented in something like Jekyll, each one requires work. As you layer more and more complicated data structures and features onto a Jekyll website, you further raise the technical burden for contributions from your team. In most cases, anyone seriously considering developing a blogging ecosystem should shift the conversation from “what features could we have” to “what are the features we absolutely cannot live without”. If the list grows too long, a static-site generator may not be the best option for your project.

On the other hand, remember that the ease of adding plugins and themes to CMSs like WordPress comes with its own costs, such as required monthly or weekly code updates and dealing with database security weaknesses and comment spam. The more a CMS magically offloads work from you, the less you and your teammates may understand about what’s under the hood of your project, and the more work the sys admin supporting your website has to take on.

A number of Jekyll websites share their underlying code on public GitHub repos (e.g. [https://github.com/scholarslab/scholarslab.org]), which you can peruse to learn more. Jekyll has friendly information on its various features; for example, if you are interested in creating categories for your posts, Jekyll’s documentation shows how. Should you want to explore similar features, Jekyll offers an example of developing further data structures in their documentation for collections. Although the Scholars’ Lab can’t guide you through adding the same features you can see on our ScholarsLab.org website, you can compare the site with the code in its repo to teach yourself how to make similar changes on your website.

Moving an existing website to Jekyll

Content management systems like WordPress[^9] have been designed to accommodate a broad variety of use cases. As there are numerous potential implementations for something like a WordPress blog, so too is it difficult to find a one-size-fits-all method for migrating away from them and into something like Jekyll. A thorough guide on how to migrate your own content from WordPress to Jekyll is out of scope for this lesson. But we can offer guidance about how to get started, point you towards resources, and offer some points to consider. Jekyll offers its own WordPress importer, for example, and Ben Balter has developed a WordPress plugin specifically for exporting data from WordPress into Jekyll. Depending on your particular approach, the process might look slightly different as to specific actions, but can be conceptually separated into a few steps.

Export your data from WordPress

When you upload content to a WordPress site, your data gets stored in a database behind the scenes. The first step to transferring a project from WordPress to another format is to get that data back out, but it can be easier said than done. As interfaces are likely to change in the future, we refer you to WordPress’s own documentation on the exact steps to separate your own content from its CMS. WordPress exports your data in a series of XML files that contain both the content and metadata (information like author, publication date, and tags) for the elements of your site. Note, however, that while these XML files might reference the images and media uploads for a website, the uploaded files themselves must be exported separately.

Programmatically migrate the exported data to a format appropriate to a new platform

The results of an export like the one described above are not likely to be immediately usable for web presentation. These XML files require further processing to turn them into the stripped down Markdown files expected by something like Jekyll. When the Scholars’ Lab migrated from WordPress to Jekyll, we used Exitwp, a Python script developed by Thomas Frössman, to facilitate the process. The script will accept a folder of XML files and produce a series of markdown files ready for Jekyll use, but, as most WordPress sites adopt specific database configurations, it was necessary to heavily modify the script for our own particular situation. Our advice is to try an export script, examine the results, and iterate. Some facility with programming might be required, a need that will likely increase depending on how complicated your WordPress setup is.

Manually correct the results to ensure accurate, clean work.

Regardless of the method you select for exporting, your content will need a lot of manual cleanup. Programmatic exporters like these will catch a majority of necessary conversions, but there will inevitably be a vast array of things needing individual clean up. WordPress shortcodes, for example, are unlikely to be readily converted into meaningful syntax for Jekyll, and even basic Markdown syntax errors will likely need to be glossed. This can be quite onerous at scale. We recommend using a robust plain text editor like Atom or Sublime Text to aid in the process. Editors like these offer color highlighting and previews for Markdown syntax, and will allow you at a glance to notice broad issues such as whole sections of a document appearing in bold.

Migrating a site from one platform to another is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process. If you are committed to migrating, take care that you do so in an organized manner. Ensure that you have done all that you can with an exporting tool before beginning to manually clean, lest you lose time correcting syntax that will be lost with the next, fresh export. For the manual cleaning phase of the process, use project management software (e.g. Trello and GitHub’s project boards are popular, free options) to track progress, facilitate collaboration if you are working in a team, and log new issues as they inevitably arise. And develop a roll-out plan that accounts for inevitable ongoing work, after the migration is finalized.

Help

Workflow recap

For folks who’ve read the longer explanations above already and just want a checklist, you can bookmark this section:

- Create new branch & switch into that branch

- Create new file or edit existing file

- Pull request when you’re ready for your work to be published

- Add reviewers

- Pass all checks

- Administrator merges pull request

- Delete the branch you just merged

- Wait several minutes to see your work on the live site

Cheatsheets

- Glossary of frequently used terms (pull, merge, branch, etc.)

- Overview of what various files in your website folder do

- Scholars’ Lab cheatsheet on basic Markdown formatting, limited to the most frequently used formatting for our needs

Troubleshooting

If you run into an issue, try reading Jekyll ‘s troubleshooting page. Besides search engines, the StackExchange site is a good place to find questions and answers from people who have run into the same problem as you in the past (and, hopefully, recorded how they solved it). You might also join the Digital Humanities Slack (anyone can join, even if you have no DH experience) and ask questions in the #DHanswers channel.

Advanced learning

Check out the following links for documentation, inspiration, and further reading about Jekyll:

Introductions to Jekyll and static sites

- Amanda Visconti, “Introducing Static Sites for Digital Humanities Projects (why & what are Jekyll, GitHub, etc.?)”

- Building a static website with Jekyll and GitHub Pages

- Alex Gil, “How (and Why) to Generate a Static Website Using Jekyll, Part 1”

- Eduardo Bouças, “An Introduction to Static Site Generators”

Deeper understanding of Jekyll and GitHub Pages

- Official Jekyll Documentation

- Jekyll “unofficially” links to two Windows + Jekyll resources: http://jekyll-windows.juthilo.com/ and https://davidburela.wordpress.com/2015/11/28/easily-install-jekyll-on-windows-with-3-command-prompt-entries-and-chocolatey/

- https://help.github.com/articles/using-jekyll-with-pages/

- Jekyll Style Guide

- Using a custom domain with GitHub Pages hosting You can purchase a domain (e.g. my-own-domain.com; $10-20/year and upwards) and switch your website to using that instead of username.github.io/repo-name but still use GitHub Pages’ free hosting.

Theming (aka visual appearance)

- Mozilla’s CSS first steps module

- The World Wide Web Consortium’s list of CSS learning articles and tutorials

- Tom Johnson, Getting started with the Documentation Theme for Jekyll: a usable theme, but also useful for cutting and pasting various neat tricks

- Jekyll documentation on themes including several theme directories

- Explore themes that are hosted on GitHub repos (e.g. this one, as many of these use a Readme file to walk you through how the theme works and how to customize it

Migrating to Jekyll

- Jekyll’s documentation on migrating existing websites

- Ben Balter’s WordPress plugin for exporting data from WordPress into Jekyll

- WordPress’s documentation on the exact steps to separate your own content from its CMS

- Exitwp, a Python script developed by Thomas Frössman that Scholars’ Lab used to migrate our blog from WordPress to Jekyll

Tools

- Robust plain text editor options: Atom, Sublime Text, Prose content editor (built on Jekyll)

- Project management options: Trello, GitHub’s project boards

Case study links

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the advice and collaboration of this lesson’s editor, Jessica Parr, as well as our reviewers Jesse Sadler and M. Willis Monroe.

The bulk of this lesson’s text was adapted from internal, context-specific documentation. That original text was co-authored by Scholars’ Lab staff, especially Amanda Visconti, Ronda Grizzle, Brandon Walsh, Laura Miller, and Beth Mitchell, and improved via testing and feedback from numerous Scholars’ Lab staff and students. The authors list for this lesson includes “Scholars’ Lab Community” to acknowledge the contributions of these collaborators to leading to this lesson.

Footnotes

[^5] See Natasha Roth Rowland’s post on ethical reasons you may decide to not use GitHub (or GitLab, or other technology).

[^6]: Usually, if you want to build something on the code of an existing repo you fork that repo. For this lesson, we decided working from a fork would be too confusing because 1) opening a pull request defaults to comparing changes between two repos rather than two branches, and 2) when actually building your own site (rather than the demo copy created in this lesson) you won’t be dealing with forks.

[^7]: If making these changes locally produces gem dependency or version errors you can’t easily solve, switching to making these changes via the GitHub.com interface will let you proceed with the lesson instead.

[^8]: If you’d really like all instructions in one place, you might wish to fork and customize Scholars’ Lab’s documentation for staff and student blogging on our ScholarsLab.org site. This offers all steps and definitions in one place. The downside is it has a number of details particular to our specific setup that you’d need to change to fit your circumstances.

[^9]: This particular lesson and case study will focus on exporting from WordPress, but Jekyll offers official documentation on how to migrate from a variety of platforms.

-

Technically, once you commit something (regardless of what branch you’re working on), what you’ve written is publicly visible to anyone who thinks to visit our repo, switch to your particular branch, and look at your commits, or to web crawlers (e.g. powering search engines or preserving popular websites). Your work won’t appear on your website until you’ve merged it back into the default branch, though. If you’d like to prevent others from seeing your in-progress and finished code in your repo, you can visit your repo’s settings to change it from a “public” to “private” repo. When this lesson was written, repos with 3 or fewer collaborators can be made private for free, but you must pay to make repos private if you work with more collaborators. ↩

-

See “Ten Hot Topics Around Scholarly Publishing” by Johnathan P. Tennant, et al. ↩

-

See Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy and Generous Thinking: A Generous Approach to Saving the University, both by Kathleen Fitzpatrick; and Open: The Philosophies and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science, edited by Rajiv S. Jhangiani and Robert Biswas-Diener. The Debates in Digital Humanities series has several contributions that began life as blog posts. ↩

-

Technically, we started off serving ScholarsLab.org from GitHub Pages, but we now use a script that updates the site on our own university servers, whenever we make changes to the default branch on GitHub. Hosting your site on a different server than GitHub Pages is an option that gives you more control over your site, including the ability to run some types of code that GitHub Pages won’t allow. As The Programming Historian emphasizes use of free resources such as GitHub Pages, in this lesson we do not cover hosting your site on servers you run yourself or pay a company to run. ↩