This is the draft website for Programming Historian lessons under review. Do not link to these pages.

For the published site, go to https://programminghistorian.org

Contents

- Introduction

- XML and TEI: towards a text encoding standard

- A Minimal TEI Document

- Conclusions

- Recommended Readings

Introduction

One of the central issues in the digital humanities has been working on and with texts: the digitization, automated character recognition, transcription, encoding, processing, and analysis of them. In this lesson, we will focus exclusively on the encoding of text, which is the process of structuring and categorizing your text with tags.

An example may help clarify this idea. Suppose we have a printed document that we have already digitized. We have the digital images of the pages, and, with the help optical character recognition (OCR) software, we have extracted their text. This text is often called ‘plain text’ because it has neither formatting (italics, bold, etc.) nor other semantic structuring.

Although it may seem strange, plain text is completely devoid of semantic meaning. To a computer, plain text is only a long chain of characters (including punctuation, spaces, and line breaks) in some encoding (for instance, UTF-8 or ASCII) of some alphabet (for example, Latin, Greek, or Cyrillic). We human beings are the ones who identify words (in one or more languages), lines, paragraphs, as we read. We also identify the names of people and places, the titles of books and articles, dates, quotations, epigraphs, references (internal and external), footnotes, and endnotes. But, again, the computer is completely ‘ignorant’ of the said textual structures in a plain text without processing or encoding. Recent advances (machine learning, NLP techniques, LLMs) can help infer structure and semantics with varying degrees of accuracy, but they do not understand the text in the way that we do.

Without human assistance–for example, through TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) Encoding–a computer cannot reliably interpret the meaning of plain text. That means, among other things, that we cannot make structured queries of that text (such as for people, for places, or for dates), nor can we systematically extract and process such information without first telling the computer which strings of characters correspond with which semantic structures. For example, we must tell the computer that this string is the name of a person, and this other name refers to the same person. We would also have to tell the computer that this is the name of a place, or this is a note in the margin that refers to a second person, or this paragraph belongs to this section of text. Encoding the text indicates (through tags and other sources) that certain strings of plain text have specific significance. That is the difference between plain text and semantically structured text.

There are many ways to encode a text. For example, we can wrap the names of people in asterisks: *Walt Whitman* or *Abraham Lincoln*. And we can wrap the names of places in double asterisks: **Camden**, **Brooklyn**, etc. We could also use underscores to indicate the names of books: _Leaves of Grass_ or _Memoranda During the War_. These signs serve to tag or mark up the text they contain in order to identify certain content in that text. It is easy to imagine that the possibilities of encoding are almost infinite.

In this lesson, we will learn to encode texts using a computer language specifically designed for them: TEI.

Software we will use

Any plain text editor (.txt format) you use will work for everything we do in this lesson. Notepad for Windows, for example, is perfectly suited for this. However, there are text editors that offer tools and functionalities designed to facilitate encoding with XML (Extensible Markup Language) and even with TEI. The most frequently used software is Oxygen XML Editor, available for Windows, MacOS, and Linux. However, it is not a free software, so we are not using it in this lesson.

For this lesson, we use the editor Visual Studio Code (VS Code, for short), which is free and is compatible with Windows, MacOS, and Linux.

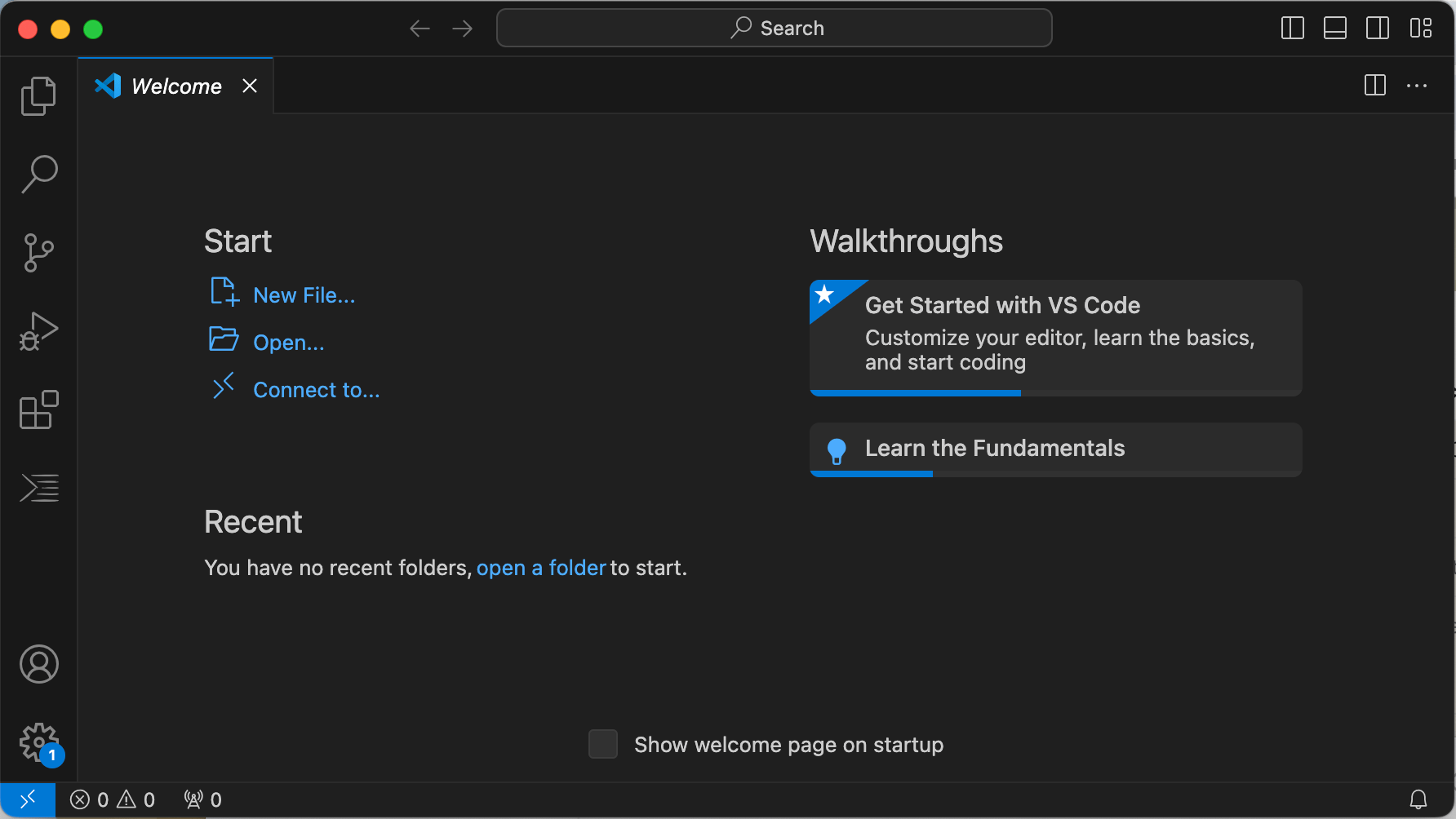

Download the most recent version of VS Code and install it on your computer. Open it and you will see a screen like this:

Figure 1. VS Code initial view.

Now we can install a VS Code extension for working more easily with XML and TEI-XML documents: Scholarly XML. You can click the Scholarly XML link to install the extension if you already have VS Code installed, or you can follow the walkthrough.

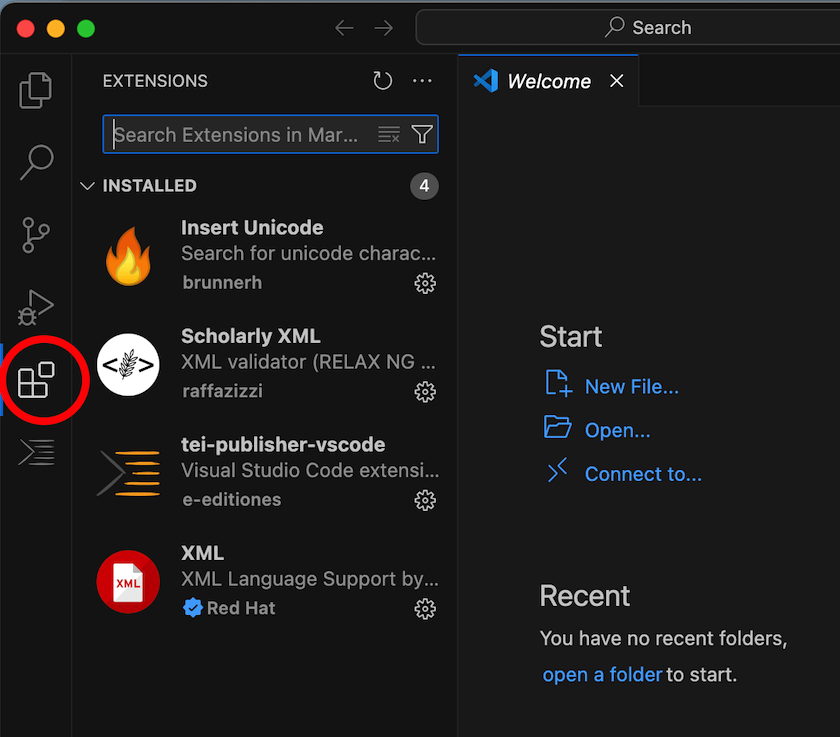

To do this, click the Extensions button in the toolbar on the left side of the window:

Figure 2. VS Code extensions.

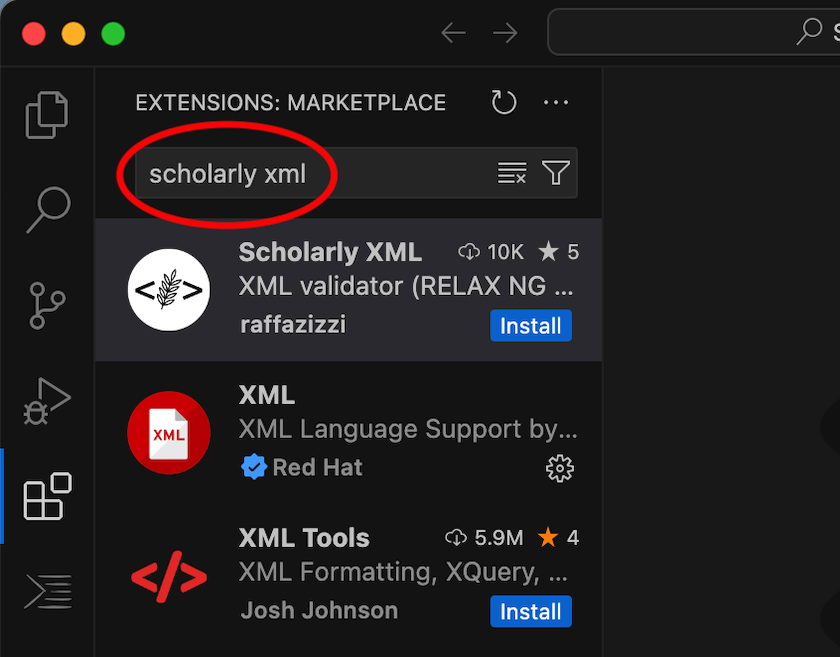

Type ‘Scholarly XML’ in the search bar.

Figure 3. Search for an extension in VS Code.

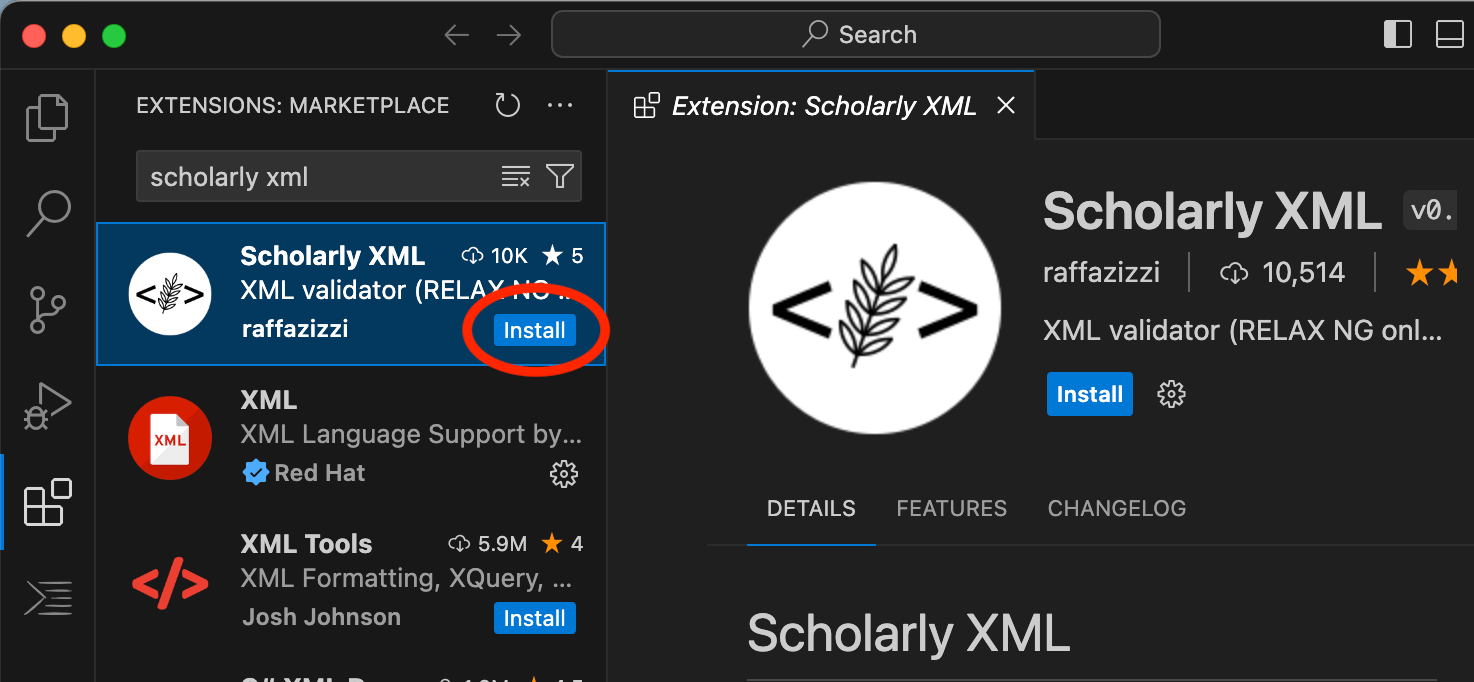

Figure 4. Install Scholarly XML in VS Code.

To learn more about Scholarly XML, you can read about it on the Visual Studio Code Marketplace or view its code repository on GitHub. For now, we will highlight several things this extension allows us to do with the code:

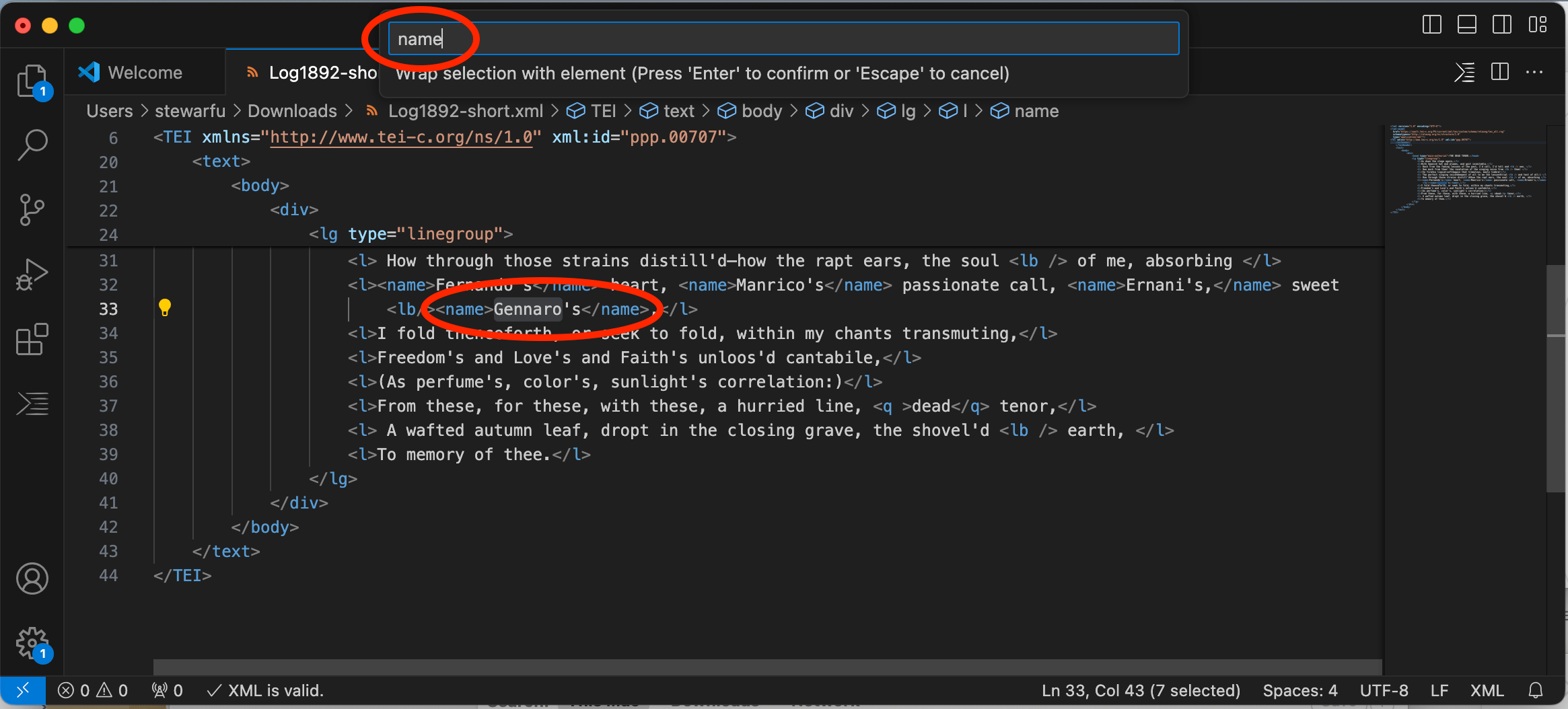

First, if you select any of the text in an XML document, you can use a keyboard shortcut to automatically enclose the text in an XML element in opening and closing tags. Well-formed XML–that is, code that is structurally sound and able to be processed–requires every XML tag to be closed. When you hit ‘ctrl+E’ (on Windows or Linux) or ‘cmd+E’ (on MacOS), VS code will open a window with the instruction Enter abbreviation (Press Enter to confirm or Escape to cancel). Next, write the name of the element and hit the enter key. The editor will then enclose the selected text between opening and closing tags. When we work with XML, automatically creating the opening and closing tags can save us a lot of time while also decreasing the likelihood of introducing typos.

Figure 5. Automatically Introduce an XML element in VS Code.

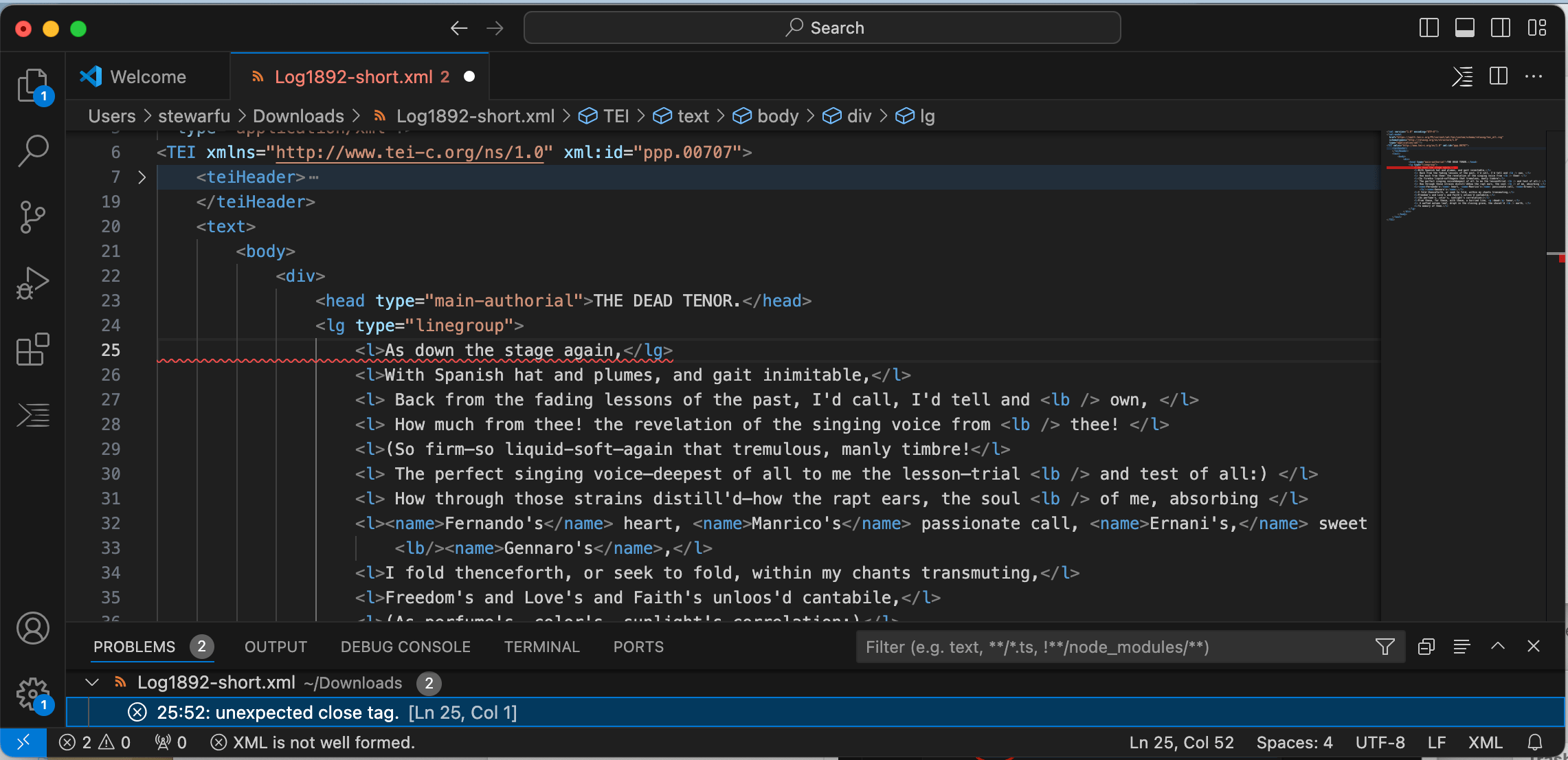

Second, we can use the extension to determine whether the document is structurally ‘well-formed’ following the syntax of XML–whether all text is inside those open and close tags and whether those tags are properly nested. The extension can also check whether the document is semantically ‘valid’ per the type of RELAX NG validation schema being used, such as the TEI schema (tei-all). We will explain the concepts of being ‘structurally well-formed’ vs ‘semantically valid’ below. The extension checks for both structural well-formedness and semantic validity automatically.

Figure 6. Automatically identify XML errors in VS Code.

To perform the second type of validation, the document must start with an XML Processing Instruction (<?xml-model>) followed by the URL of the schema you want to use, like this:

<?xml-model href="http://www.tei-c.org/release/xml/tei/custom/schema/relaxng/tei_all.rng" type="application/xml" schematypens="http://relaxng.org/ns/structure/1.0"?>

<?xml-model href="http://www.tei-c.org/release/xml/tei/custom/schema/relaxng/tei_all.rng" type="application/xml"

schematypens="http://purl.oclc.org/dsdl/schematron"?>

You can download the basic template of a TEI-XML document, with these lines included.

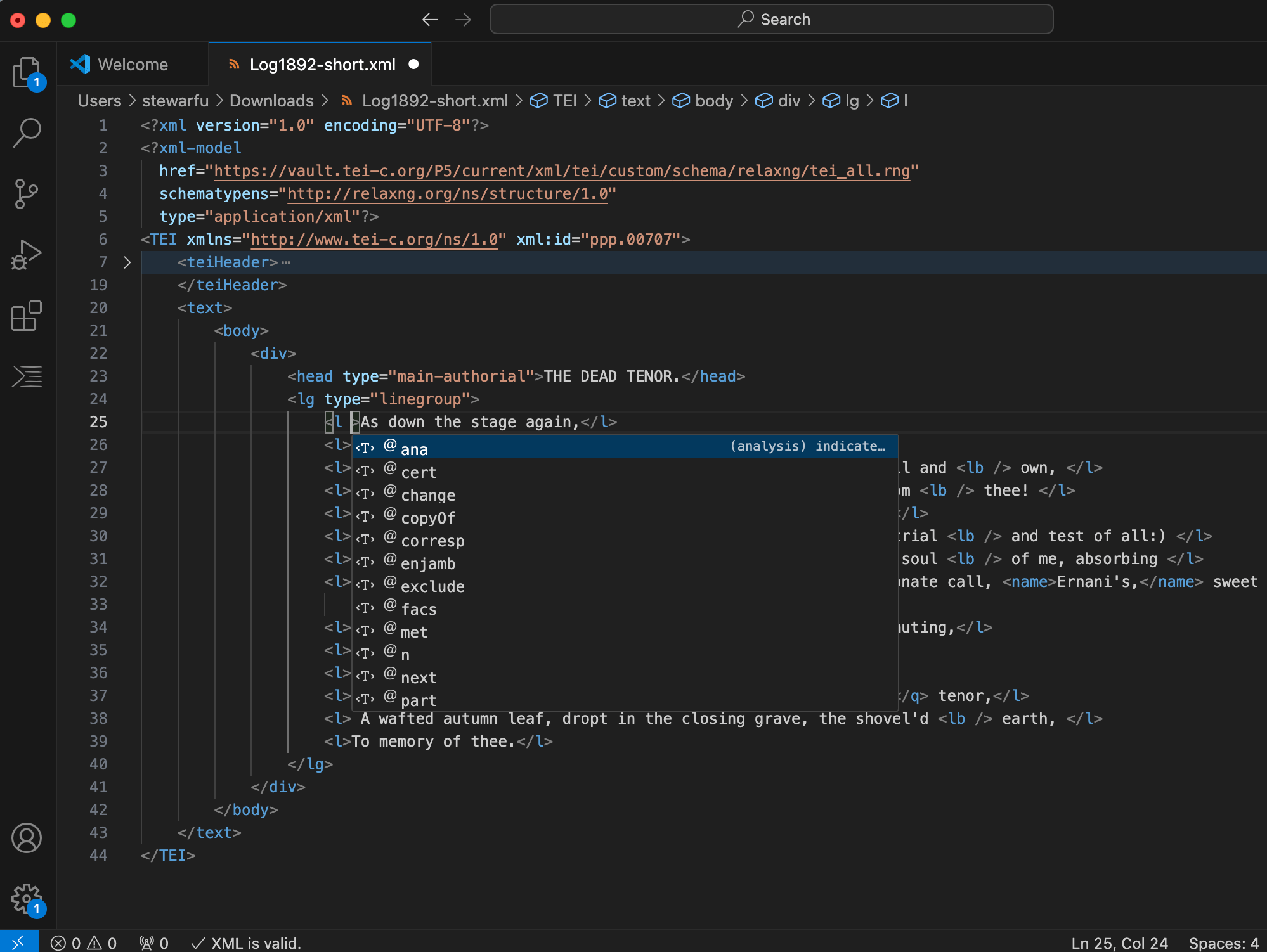

Third, the extension also offers tools to autocomplete the XML code as part of the validation for the schema RELAX NG. For example, if we introduce the element <l> (used to mark a line of poetry), we can hit the space bar after the opening <l> and VS Code will show us a list of possible attributes to select from the menu:

Figure 7. Menu of autocomplete options while encoding XML in VS Code.

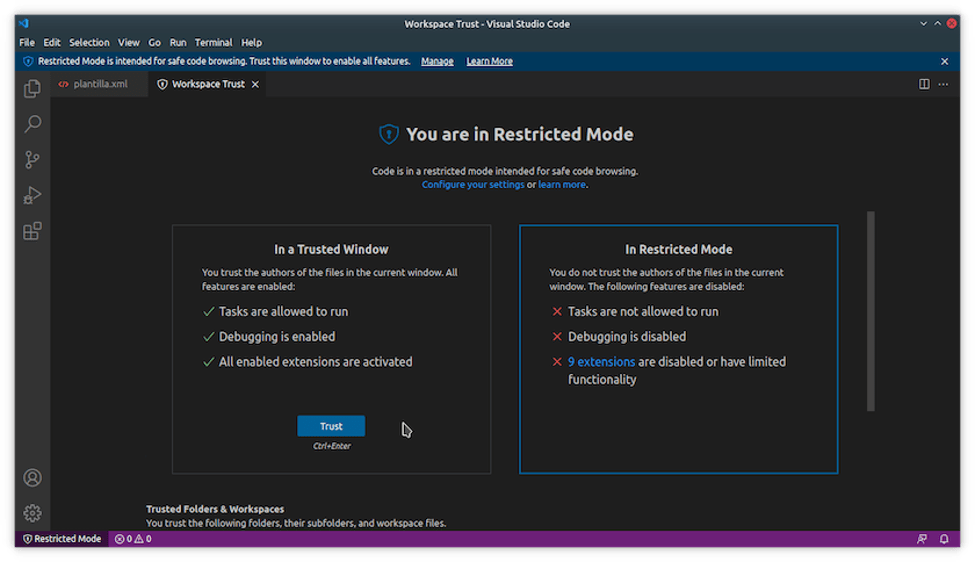

Now, in order to use Scholarly XML or other VS Code extensions, it is necessary to check that the editor isn’t in restricted mode, as it appears in this window:

Figure 8. The ‘restricted mode’ notice in VS Code.

This mode prevents extensions or document code from executing instructions that could damage our computer. Because we are working with a trusted extension, we can deactivate the restricted mode by clicking the hyperlink above that says Manage and then the button that says Trust.

Figure 9. Exit restricted mode in VS Code.

Now that we have configured our editing software, we can start to work in TEI-XML.

Visualization vs. categorization

Those who are familiar with the markup language Markdown–common today in online technical forums, as well as in GitHub, GitLab, and other code repositories–will surely recognize the use of elements like asterisks (*), underscores (_), and number signs (#) to make text appear a certain way in a browser. For example, text wrapped in single asterisks will be shown in italics, and text wrapped in double asterisks will be in bold. In fact, the text of this lesson is written in Markdown following these conventions.

However, Markdown is a procedural markup language, focused on how a text should be processed and displayed, rather than a descriptive markup language like TEI. Descriptive markup languages label pieces of text for their semantic or structural meaning rather than how they should appear on a screen. When we mark a text fragment to encode it in TEI, we do so without worrying at first how the text was originally represented or how it might eventually be represented in the future. We are only interested in the semantic or structural function that a particular bit of text may have. Therefore, we must try to precisely identify the functions or categories of text, setting aside, as much as possible, the way in which the text is shown on the page or screen.

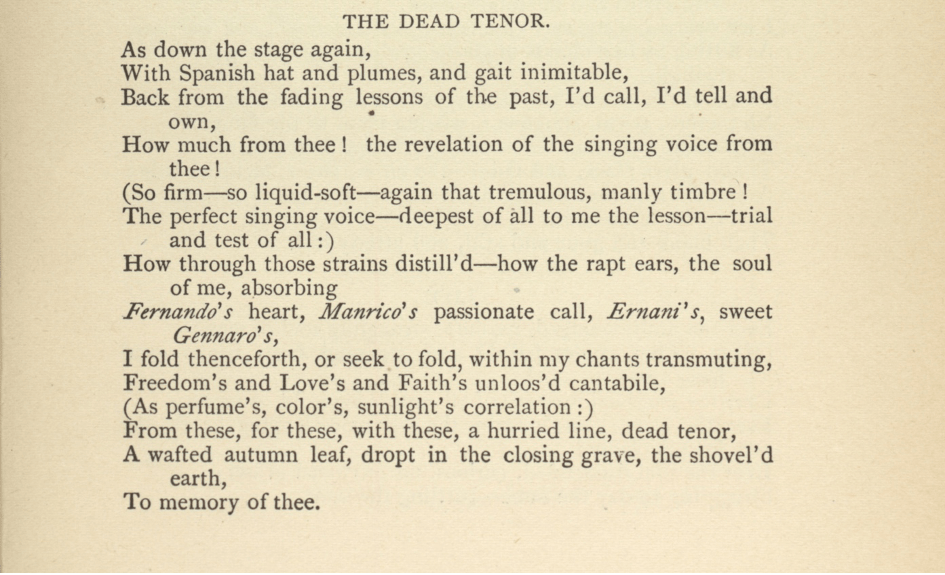

Let’s clarify this by returning to our first example. Suppose we have a digitized text where all the proper names appear in italics, such as in Whitman’s The Dead Tenor:

Figure 10. A digitized excerpt of Leaves of Grass.

As we see below, TEI allows us to encode, as part of a series of tags, the text that we want to categorize. For example, we can use the tag <name> to mark the proper names in the text, as in:

<name>Fernando</name>’s <name>Manrico</name>’s passionate call, <name>Ernani</name>’s, sweet <name>Gennaro</name>’s

Later we will see in greater detail what a tag is and how it works (or, more precisely, what an ‘element’ is and how it works) in XML and TEI. For now, we can see that the tag doesn’t tell us that the text was represented in italics (or anything else about its appearance) in the original. It only shows that the text inside the tag is part of the category of names, regardless of how it is represented. In fact, we can exhaustively encode a document with hundreds or thousands of tags, without any of them affecting the final appearance of the eventual display.

XML and TEI: towards a text encoding standard

From the beginnings of digital humanities in the 1960s, there have been many attempts at text encoding. Nearly every encoding project had its own standard, meaning the projects were incompatible and untranslatable, making collaborative work more difficult and even impossible.

To resolve this problem, about twenty years later, a convention of a large number of researchers from around the world, especially from universities in primarily English-speaking countries, established a new standard for text encoding: the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI).

TEI is one way to use the markup language XML, which is why it can sometimes be called TEI-XML (or also XML/TEI). For its part, XML (which is the abbreviation for ‘eXtensible Markup Language’) is a computing language whose purpose is to describe, using a series of markings or tags, a particular text object. XML is a markup language, differentiated from programming languages like C, Python, or Java, which describe objects, functions, or processes which must be executed by a computer. XML doesn’t provide specific tags so much as a system for how any tag should be used; it is TEI that provides the vocabulary for what tags can appear and where.

XML

In this lesson, we will not go into detail on the syntaxes and functions of XML. Therefore, we recommend you take a look at M. H. Beals’s lesson _Transforming Data for Reuse and Re-publication with XML and XSL for more information on XML, and explore the bibliography and references at the end of this lesson.

For now, all you need to know is that every document in XML must comply with two basic rules to be valid:

- It must have a single root element (containing all other elements, if any)

- Every opening tag must have a matching closing tag

Luckily, the XML code editors like VS Code (with the extension Scholarly XML) or OxygenXML allow us to easily detect this type of error.

What is TEI?

XML is a language that is so general and abstract that it is totally indifferent to its content. For example, it can describe texts as different as a Classical Greek work from the eighth century BCE and a message that a smart thermostat would send to the smartphone app that controls it.

TEI is a particular dialect of XML. It is a series of rules that determine which elements and which attributes are permitted in a document of a certain type. More precisely, TEI is a mark-up language to encode texts of all kinds. Documents are encoded in TEI so that they can be processed by a computer, so that they can be analyzed, transformed, reproduced, and stored depending on the needs and interests of the users (both the real people and the computers). That is why we can say that TEI is the heart of the digital humanities (or at least one of their hearts!). It is the standard to work computationally with a group of objects that are traditionally central to the humanities: texts. So, while XML does not care about whether the elements of a document describe text, TEI is designed exclusively to work with texts.

The types of elements and attributes that are permissible in TEI, and the relationships that exist between them, are specified in the TEI Guidelines. For example, if we want to encode a poem, we can use the TEI element <lg> (line group). The TEI guidelines determine which attributes can be used on which elements and which of those elements, at the same time, contain or can be contained by other elements. TEI determines that every element <lg> should contain at least one element <l> (verse line).

For an example, let’s examine the first verses of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

In plain text:

O captain! My captain! Our fearful trip is done

The ship has weathered every rack, the prize we sought is won;

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people are exulting

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring

We can put the following lines encoded in TEI:

<lg met=“-+|-+|-+|-+|-+|-+|-+” rhyme=”aabb”>

<l n=”1”>O captain! My captain! Our fearful trip is done</l>

<l n=”2”>The ship has weathered every rack, the prize we sought is won;</l>

<l n=”3”>The port is near, the bells I hear, the people are exulting</l>

<l n=”4”>While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring</l>

</lg>

In this case, we can put the valid attribute @rhyme on the element <lg> to encode the rhyme scheme of the passage (aabb). The attribute @met indicates the meter of the verse (iambic heptameter). Finally, the attribute @n indicates the number of the verse inside the stanza.

The difference between the plain text and the encoded version for this part of the sonnet allows us to start to see the advantages of TEI as a markup language for text. Not only does the encoded version explicitly say that the lines of text are lines of a poem, but it also identifies the rhyme scheme and meter. Once we have encoded a complete poem, or all the poems in a collection, we can, for example, use a software to perform structured queries to show us all the poems that have a certain rhyme scheme or meter. Or, we can use (or create) an application to determine how many stanzas in the poems of Leaves of Grass (if any) have imperfect meter. Or, we can compare the distinct versions of the sonnets (the ‘witnesses’ of the handwritten and printed versions), in order to compile a digital edition of them.

Now, all of this and much more is possible only by virtue of the fact that we have made explicit, thanks to TEI, the content of those sonnets. If you only had had their plain text versions, it would be technically impossible to leverage computing tools designed for editing, transforming, visualizing, analyzing, and publishing.

A Minimal TEI Document

Now, let’s examine the following minimal document of TEI:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<TEI xmlns="http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0">

<teiHeader>

<fileDesc>

<titleStmt>

<title>Title</title>

</titleStmt>

<publicationStmt>

<p>Publication information</p>

</publicationStmt>

<sourceDesc>

<p>Information about the source</p>

</sourceDesc>

</fileDesc>

</teiHeader>

<text>

<body>

<p>Some text...</p>

</body>

</text>

</TEI>

The first line is the traditional declaration for an XML document. The second line contains the first element, or ‘root’ element of the document: <TEI>. The attribute @xmlns with the value http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0 simply declares that all the ‘child’ elements and attributes in <TEI> belong to the ‘namespace’ of TEI (represented here by the URL). We will not have to worry about this later on.

The interesting thing comes later in lines 3-16, right after the ‘root’ element, which contain (respectively) the two following ‘child’ elements:

Now we will see what those elements consist of.

The <teiHeader> Element

All of the metadata in the document is encoded in the element <teiHeader>: the title; authors; where, when, and how they were published, your source, where your source was taken from, etc. It is common for people who are starting to learn TEI to overlook that information, filling those fields with generic and incomplete data. However, the information in <teiHeader> is essential to the task of encoding, because it serves to identify with total precision the encoded text.

<teiHeader> should contain at least an element called <fileDesc> (from ‘file description’), which should then contain three ‘child’ elements:

<titleStmt>(from ‘title statement’): the information about the title of the document (inside<title>); optional elements could also include data about the author(s) (inside<author>)<publicationStmt>(from ‘publication statement’): the information about how the work is published and made available (that is, the TEI document itself; not the original source). In this sense it is analogous to the information about the publisher on the copyright page of a book. It can be a descriptive paragraph (inside the generic element for a paragraph,<p>), or it can be structured in one or more of the following elements:<address>: the postal address of the person who edited or encoded the document<date>: the date the document was published<pubPlace>: the place the document was published<publisher>: the person who edited or encoded the document<ref>(or<ptr>): an external link (URL) where the document is available

<sourceDesc>(from ‘source description’): the information about the source from which the encoded text is being taken. It can be a descriptive paragraph (inside the generic element for a paragraph,<p>). It can also be structured in many ways. For example, it can use the element<bibl>and include the bibliographic reference without more structuring elements (for example,<bibl>Walt Whitman, *Leaves of Grass* Brooklyn, New York: Walt Whitman, 1855</bibl>). Or, it can contain a structured reference in<biblStruct>, which contains other relevant elements.

Suppose we want to encode Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, starting with this freely available edition on the Walt Whitman Archive. The <teiHeader> of our TEI document could look like the following:

<teiHeader>

<fileDesc>

<titleStmt>

<title>Leaves of Grass</title>

<author>Walt Whitman</author>

</titleStmt>

<publicationStmt>

<p>

Nicole Gray, Kenneth M. Price, Ed Folsom, Kelly Tetterton, Zach Bajaber, Brett Barney, and Elizabeth Lorang contributed to this encoding. Full TEI encoding available on the Whitman Archive at: (whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.00271)[whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.00271].

</p>

</publicationStmt>

<sourceDesc>

<p>

The text is from the 1855 edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The original copy used in this transcription is at the University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections & University Archives. The full text, encoding, and images are available online on the Whitman Archive at: (whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.00271)[whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.00271].

</p>

</sourceDesc>

</fileDesc>

</teiHeader>

Note that, in the

<sourceDesc>paragraph, the ampersand in “Special Collections & University >Archives” cannot be written with the ampersand character (&) in XML. Instead, it must be keyed in with its escape sequence,&.

This is the minimum information required to identify the encoded document. It tells us the title and author of the text, the person responsible for the encoding, and the source from which the text was taken.

However, it is possible–and sometimes desirable–to specify more details in the metadata of a document. For example, we can consider this other version of <teiHeader> for the same text:

<teiHeader>

<fileDesc>

<titleStmt>

<title>Leaves of Grass</title>

<author>Walt Whitman</author>

</titleStmt>

<publicationStmt>

<publisher>The Walt Whitman Archive</publisher>

<pubPlace>University of Nebraska-Lincoln</pubPlace>

<date>2022</date>

<availability>

<p>The text encoding was created and/or prepared by the Walt Whitman Archive and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Any reuse of this material should credit the Walt Whitman Archive</p>

</availability>

</publicationStmt>

<sourceDesc>

<biblStruct>

<monogr>

<author>Walt Whitman</author>

<title>Leaves of Grass</title>

<imprint>

<pubPlace>Brooklyn, NY</pubPlace>

<date>1855</date>

</imprint>

</monogr>

</biblStruct>

</sourceDesc>

</fileDesc>

</teiHeader>

The choice about how complete to make the <teiHeader> depends on the availability of the information, as well as the purposes of the encoding and the interests of the editor. Now, although the metadata in <teiHeader> in a TEI document don’t necessarily appear literally in encoded text, they are not irrelevant to the process of encoding, editing, and eventually transforming. In fact, the extent that the <teiHeader> has been correctly and completely encoded is the same extent that you can extract and transform the information contained in the document.

For example, if it is important to us to distinguish between the different editions and imprints of Leaves of Grass, the information contained in <teiHeader> about those distinct documents would be sufficient to differentiate between them automatically. In effect, we can leverage the elements <edition> and <imprint> to this end, and with the help of technology like XSLT, XPath and XQuery we can locate, extract, and process all of this information.

In conclusion, the more complete and thoroughly the metadata about the text is encoded in <teiHeader> in our TEI documents, the more control we will have about its identity and display online.

The <text> element

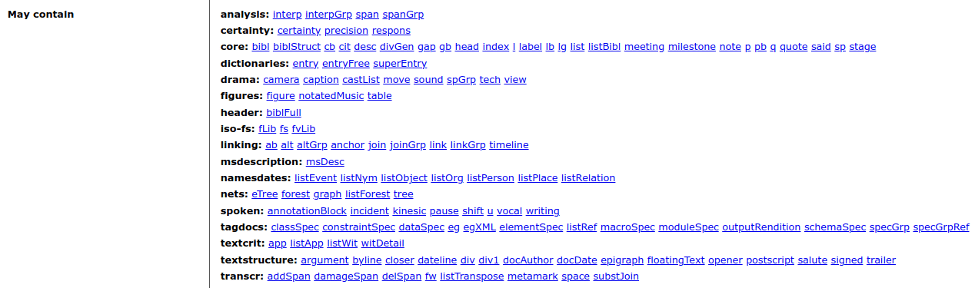

As we saw above in the minimal document, <text> is the second child of <TEI>. It contains all of the text in the document, properly speaking. According to the TEI guidelines, <text> can contain a series of elements in which the text must be structured.

Figure 11. Possible elements within <text>.

The most important of these elements is <body>, which contains the main body of the text. However, other important child elements of <text> are <front>, which contains the frontmatter of a text (introduction, prologue, etc), and <back>, which contains the backmatter (final pages, appendices, indexes, etc.).

For its part, the <body> element can contain many other elements:

Figure 12. Possible elements within <body>.

At first glance, all the possibilities may seem overwhelming. However, it is important to remember that a text is usually naturally divided into sections or parts. It is advisable, therefore, to use the element <div> for each of these sections, and to use the attribute @type or @n to distinguish different classes and their positions in the text (for example, <div n=“3” type= “subsection”>…</div>).

If our text is short and simple, we can use just one <div>. For example:

<text>

<body>

<div>

<!-- All of our text goes here -->

</div>

</body>

</text>

But if our text is more complex, we can use various <div> elements:

<text>

<body>

<div>

<!-- The text of our first section or division goes here -->

</div>

<div>

<!-- The text of our second section or division goes here -->

</div>

<!-- etc. -->

</body>

</text>

The structure of our TEI document should, at least in principle, be similar to the structure of our text object, that is the text we want to encode. Therefore, if our text object is divided in chapters, and those chapters are divided into sections or parts, and those, in turn, in paragraphs, it is recommended that we replicate the same structure in the TEI document.

For the chapters and the sections, we can use the element <div>, and for the paragraphs the element <p>. Let’s look, for example, at the following schema:

<text>

<body>

<div type="chapter" n="1">

<!-- This is the first chapter -->

<div type="section" n="1">

<!-- This is the first section -->

<p>

<!-- This is the first paragraph -->

</p>

<p>

<!-- This is the second paragraph -->

</p>

<!-- ... -->

</div>

</div>

<!-- ... -->

</body>

</text>

Although TEI allows us to exhaustively encode many of the aspects and properties of a text, sometimes we are not interested in all of them. Plus, the process of encoding can take more time than it needs to if we encode elements that we are never going to take advantage of in the eventual transformation. For example, if we want to encode the text of a printed edition, the line breaks in the paragraphs may not be relevant to our encoding.

In this case, we can ignore those breaks and can keep only the paragraph breaks, without going into greater detail. Or perhaps we feel the temptation of systematically encoding all of the dates and places (with the elements <date> and <placeName>, respectively) that appear in our text object, even though we never use them later. Encoding them is not a mistake, per se, but we may waste valuable time by doing so.

In conclusion, we can formulate the ‘golden rule’ of encoding: we encode all the elements that have a certain meaning for us, but only those elements, so that we can eventually use them for specific purposes.

Conclusions

In this first part of the lesson, we have learned:

- What it means to encode a text

- What XML and XML-TEI documents are

The second part of this lesson is not yet available in English, but is forthcoming. In the Spanish original of part 2, however, you can explore two examples of encoded texts in greater detail.

Recommended Readings

- The TEI Guidelines have the complete documentation of TEI.

- A good tutorial for XML is available at https://www.w3schools.com/xml/ and at https://www.tutorialspoint.com/xml/index.htm.

- The TEI Consortium also offers a good introduction to XML.

- The official documentation of XML is available at the W3C Consortium. There is also documentation for all of the XSL family, including XSLT.

- The Mozilla Foundation also offers good documentation about XSLT and associated technologies.

- A Programming Historian lesson about XML and the transformations of XSL is Transforming Data for Reuse and Republication with XML and XSL by M. H. Beals.