This is the draft website for Programming Historian lessons under review. Do not link to these pages.

For the published site, go to https://programminghistorian.org

Contents

- Introduction, Lesson Goals, and Data

- Loading in Data about Sister Cities in Europe

- Creating Our First Graph

- Other Geoms: Histograms, Distribution Plots and Boxplots

- Advanced Manipulations Regarding the Look of Graphs

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources

Introduction, Lesson Goals, and Data

Historians now increasingly face the task of gathering and analyzing data, and plots are important in visualizing that data. Using R and the powerful package ggplot2, we can create useful and beautiful plots to give a glance into our data and make it easier to communicate our findings to the public and a broader audience.

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to do the following with the ggplot2 package:

-

Create different types of plots: bar plots, histograms, boxplots, scatterplots, etc.

-

Manipulate the aesthetic of plots, such as colors or sizes.

-

Add meaningful labels to plots.

-

Create grids of plots for data comparison.

-

Create novel plots with ggplot2 extensions.

This tutorial assumes you have a rudimentary knowledge of R. Programming Historian has lessons covering different topics, and we recommend beginning with Taryn Dewar’s R Basics with Tabular Data and Nabeel Siddiqui’s Data Wrangling and Management in R if you do not have this background.

Several data analysis methods exist, but we will concentrate on graphical representations in this tutorial. In R, we have three main possibilities for creating graphs: the plotting functions provided by the standard installation of R, the lattice package, and finally, ggplot2, created by Hadley Wickham.

ggplot2 has many advantages over the other possibilities:

-

It relies on a theoretical framework (detailed below) that assures your graphs meaningfully convey information.

-

It is relatively simple to use while remaining powerful.

-

It creates publication-ready graphs.

-

It has extensions that the community has developed to enhance its possibilities, such as the addition of new functions, graphs, and themes.

-

It can also be used to create maps (which is although not covered in this lesson).

Creating graphics is a complicated issue since we need to take into account various aspects of our data: the information we want to convey, what type of graph we want to convey that information (scatterplots, boxplots, histograms, and so on), the elements of the graph we wish to tweak (axes, transformation of variables, legends, etc.), and more. To provide a common framework, ggplot2 is based on a theoretical framework known as the grammar of graphics (hence the gg in the name ggplot2), as detailed by Leland Wilkinson. If all this sounds complicated at first, don’t panic! You only need to know a bit about the grammar to make your first graph.

The idea behind the grammar of graphics is that all plots are composed of a series of seven interrelated layers:

-

Data: The material we will use to analyze for our visualization.

-

Aesthetics: The ways that visual properties map onto so-called geoms (Geometric Objects, see below). In most cases, this determines how we want to display our data (position, color, shape, fill, size, etc.)

-

Scales: The mapping and normalization of data for visualization.

-

Geometric Objects (geoms in ggplot2 parlance): The way we want to represent our data. You can think of this as determining the type of graph you want, such as a bar graph, line graph, or histogram.

-

Statistics: Statistical calculations we may want to run our data before visualizing it.

-

Facets: The ability to categorize and divide data into multiple sub-graphs.

-

Coordinate Systems: Determines how ggplot2 positions different geoms on the plot. The most common coordinate system is the Cartesian coordinate system, but ggplot2 can also plot polar coordinates and spherical projections.

To use ggplot2, we need first to install and load it. We recommend installing the tidyverse, which includes ggplot2. The tidyverse is a collection of R packages that work together to provide a consistent and efficient workflow for data manipulation, exploration, and visualization. At the core of the tidyverse philosophy is the concept of “tidy data”, a standardized way of structuring data to make it easier to work with. In tidy data, each variable is a column, each observation is a row, and each type of observational unit is a table. This structure allows for a consistent and predictable way of working with data across different packages and functions within the tidyverse. It is brilliantly explained in the book R for Data Science. Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize and Model Data written by Hadley Wickam and others and is available online.

install.packages("tidyverse")

library("tidyverse")

Loading in Data about Sister Cities in Europe

For this tutorial, we will look at sister cities around the world. This data comes from Wikidata and consists of sister cities, which are pairs of cities located in different countries with a partnership to promote cultural and commercial ties. The modern concept of sister cities was conceived after World War II to foster friendship and understanding between different cultures and to promote trade and tourism. These partnerships can often involve student exchanges, business relationships, and cultural events.

As historians, we can leverage data on sister cities to explore new questions about international connections and their implications. By examining this data, we can investigate whether regional, cultural, economic, or religious factors influence the formation of sister-city partnerships. For instance, we can assess if geographic proximity, shared language, or similar population size play a role in the likelihood of two cities establishing a relationship. We can also explore whether historical tensions or alliances, such as those between Germany, France, and Poland, or the shared linguistic heritage of Spanish-speaking cities in the Americas, shape these partnerships.

Throughout this tutorial, we will use ggplot2 to illuminate some of these questions and others. Our approach will be largely exploratory, aiming to identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data. We hope that we can uncover new insights and generate hypotheses for further research by doing so. You can download the dataset at this link.

Loading Data with readr

Before importing data, it is important to understand how it may be formatted. Common spreadsheet applications, such as Microsoft Excel or Apple Numbers, place data in a proprietary format. While there are packages to read in Excel data, such as readxl, it is recommended to use open formats, such as .csv (comma-separated values) or .tsv (tab-separated values) whenever possible. This has the advantage of being more accessible and compatible with a wider range of software tools. Additionally, these formats are more likely to be readable in the future as they are not tied to any specific application or version.

R has built-in commands for reading in these files, but we will use the package readr from the tidyverse ecosystem. readr can read most of the common formats you will encounter. For our particular dataset, we will be reading in a .csv file. Let’s go ahead and download the dataset and place it in our project’s current working directory. We will first need to load the readr library. Next, we can use the read_csv() with the file path. Let’s go ahead and place the dataset in our project’s current working directory.

eudata<-read_csv("sistercities.csv")

Let’s take a look at our data:

eudata

# A tibble: 13,081 x 15

[etc]

As you can see, the tidyverse converts our data to a “tibble” rather than a “data frame.” Tibbles are a part of the tidyverse universe that serve the same function as data frames but make decisions on the backend about importation and how R displays the data.

R is a relatively old language, and as a result, defaults that made sense during the original implementation are less helpful now. Tibbles, unlike data frames, do not change the name of variables, convert the type of input, or create row names. You can learn more about tibbles here. If this does not make sense, don’t worry! In most cases, we can treat tibbles exactly like data frames and easily convert between the two. If you need to convert your data frame to a tibble, use the as_tibble() function with the data frame’s name as the parameter. Likewise, to convert back to a data frame, use the as.data.frame() function.

We will start by exploring the data of six EU countries: Germany, France, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, and Bulgaria (three Western European countries and three Eastern European countries). As you saw above, we have a tibble called “eudata” with six countries that contains 13081 rows with 12 variables.

The tibble contains comprehensive information about sister city relationships. For each pair of cities, we have data on the origin city (origincity) and its corresponding country (origincountry), along with its geographical coordinates (originlat and originlong) and population (originpopulation). Similarly, we have the same set of information for the destination city: the city name (destinationcity), country (destinationcountry), coordinates (destinationlat and destinationlong), and population (destinationpopulation).

In addition to the city-specific data, the tibble provides two more variables that offer insights into the nature of the sister-city relationships. The dist column indicates the distance between the two cities in kilometers, allowing us to explore the role of proximity in these partnerships. Lastly, the eu column is a categorical variable that informs us whether the destination city is located within the European Union or not, enabling us to investigate potential patterns related to the EU.

Creating Our First Graph

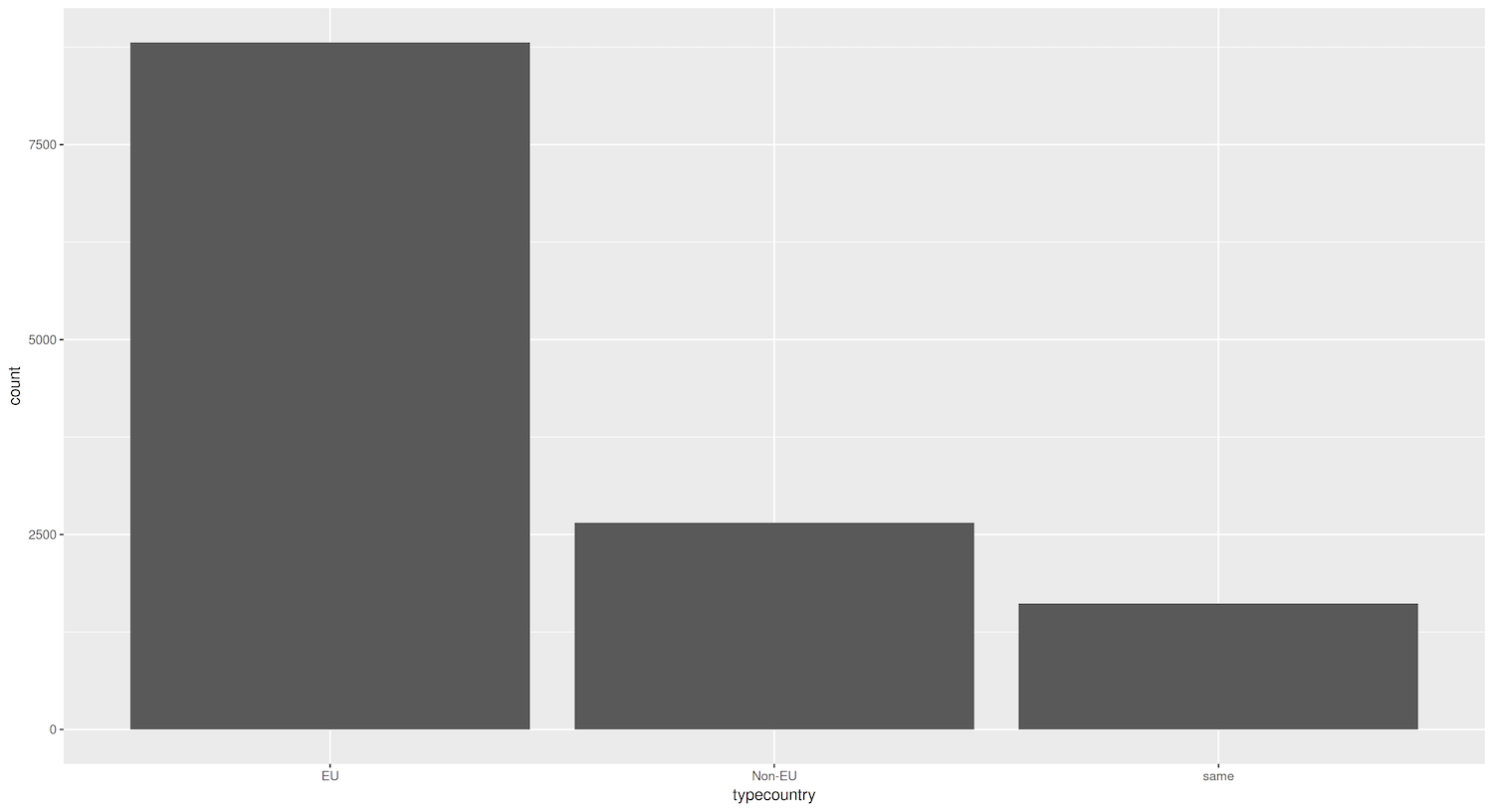

Let’s begin by exploring a specific question: Do European cities tend to form stronger sister-city relationships with cities in the same country, cities in other EU countries, or cities outside the EU? To investigate this, we can create a bar plot that visualizes the percentage of destination cities falling into these three categories.

In ggplot2, we begin with the following code:

ggplot(eudata, aes(x = typecountry)) +

geom_bar()

Figure 1. Bar graph showing the total count of destination cities that are domestic, EU, and non-EU)

The first parameter of the ggplot() function is the tibble or data frame containing the information we are exploring, while the second parameter reflects the “aesthetics” of the graph. Aesthetics, as you may recall from earlier, defines the variables in our data and how we want to map them to visual properties. These two are the basis of any plot.

The geom() (from geometries) layer tells ggplot2 the type of graph we want to produce. Since we want to create a barplot, we need the geom_bar() layer, which is done by adding the + command.

Understanding the ggplot() syntax can be tricky at first, but once it makes sense, you can see the power of the standardized grammar of graphics framework that underpins ggplot2. One way you can think of this grammar is to view the creation of plots like constructing a sentence. In our example, we told R: “Create a ggplot graph using the data in eudata and map the variable typecountry to x and add a layer called geom_bar().” This structure is straightforward except for using aes(), which means in ggplot parlance aesthetics. It is not a telling expression, but the idea is simple: we tell R to map variables in the data to visual properties (aesthetics) of geoms in the graph. Again, do not panic if you do not understand it completely. We will go into more depth later.

We now have our first plot! You may notice that ggplot2 has made some decisions on its own: background color, font size of the labels, etc. The default settings are usually sufficient, but we can customize these aspects if needed.

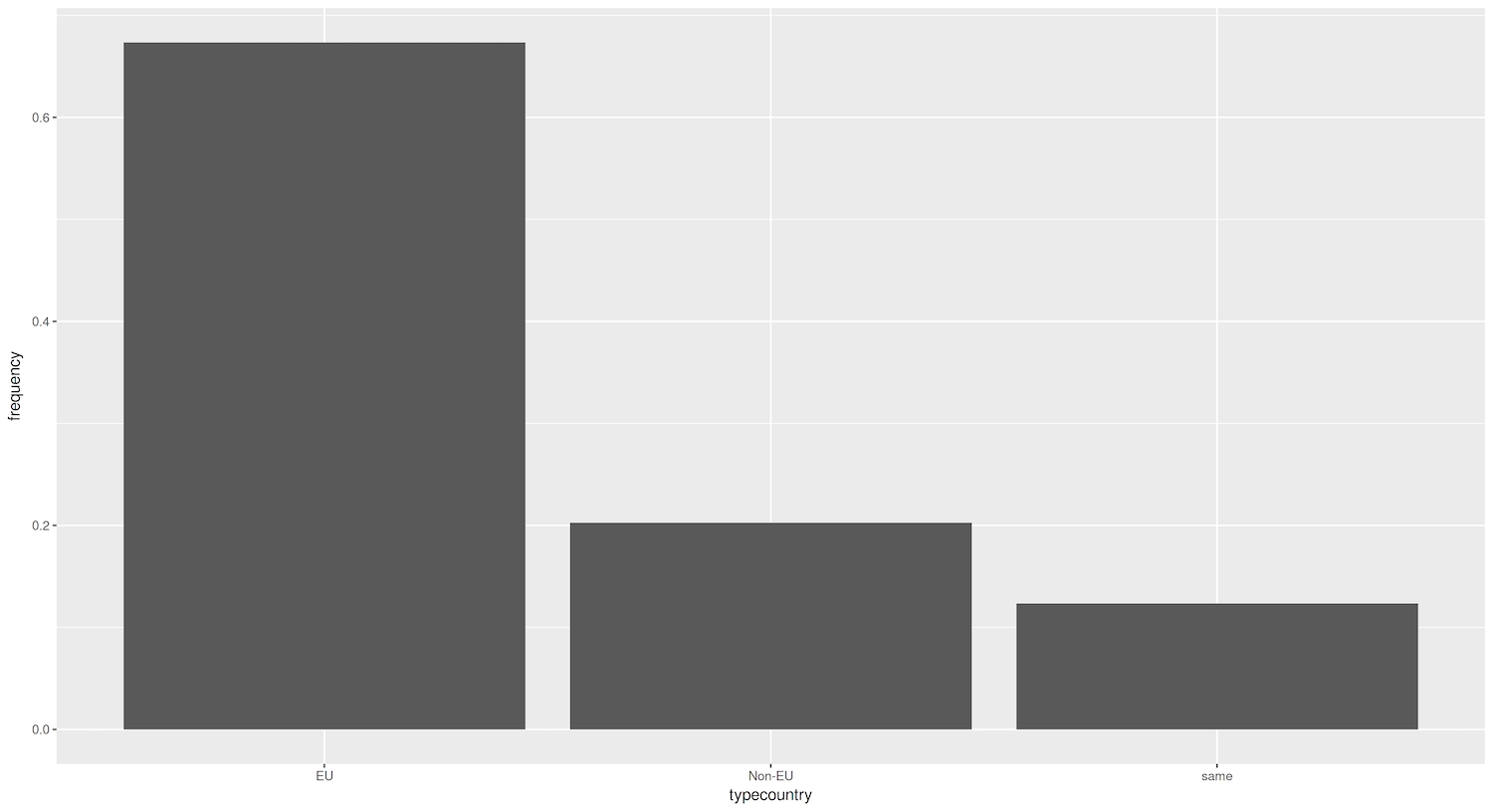

Because we work within a consistent syntax, we can easily modify our plots to look different or display different data. For instance, let’s say we want to look at percentages rather than raw counts. Using the following code, we can create a new tibble that calculates the percentage and adds a new column named perc with the percentage values (again, see the tutorial Data Wrangling and Managment in R about dplyr for details if this code does not make sense to you). Once we have done so, we only need to make a few changes :

# Aggregate the data per type of country and add a new column with percentages

eudata.perc <- eudata %>%

group_by(typecountry) %>%

summarise(total = n()) %>%

mutate(perc = total/sum(total))

ggplot(data = eudata.perc, aes(x = typecountry, y = perc)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity")

Figure 2. Bar graph showing percentage of destination cities that are domestic, EU, and non-EU

There is an important difference between the first plot and this one. In the previous plot, ggplot2 counted the number of cities in every group. In our new plot, the tibble contains the values for the bars. This information is in the column perc, so we add y = perc as a parameter of aes(), but this is not enough. The tricky part is that by default geom_bar() will use the parameter stat = "count". This means that it will count how many times a value appears. In other words, it aggregates the data for you. Since the data is already aggregated, we inform ggplot2 that we have already calculated the values in the column by using the parameter stat = "identity".

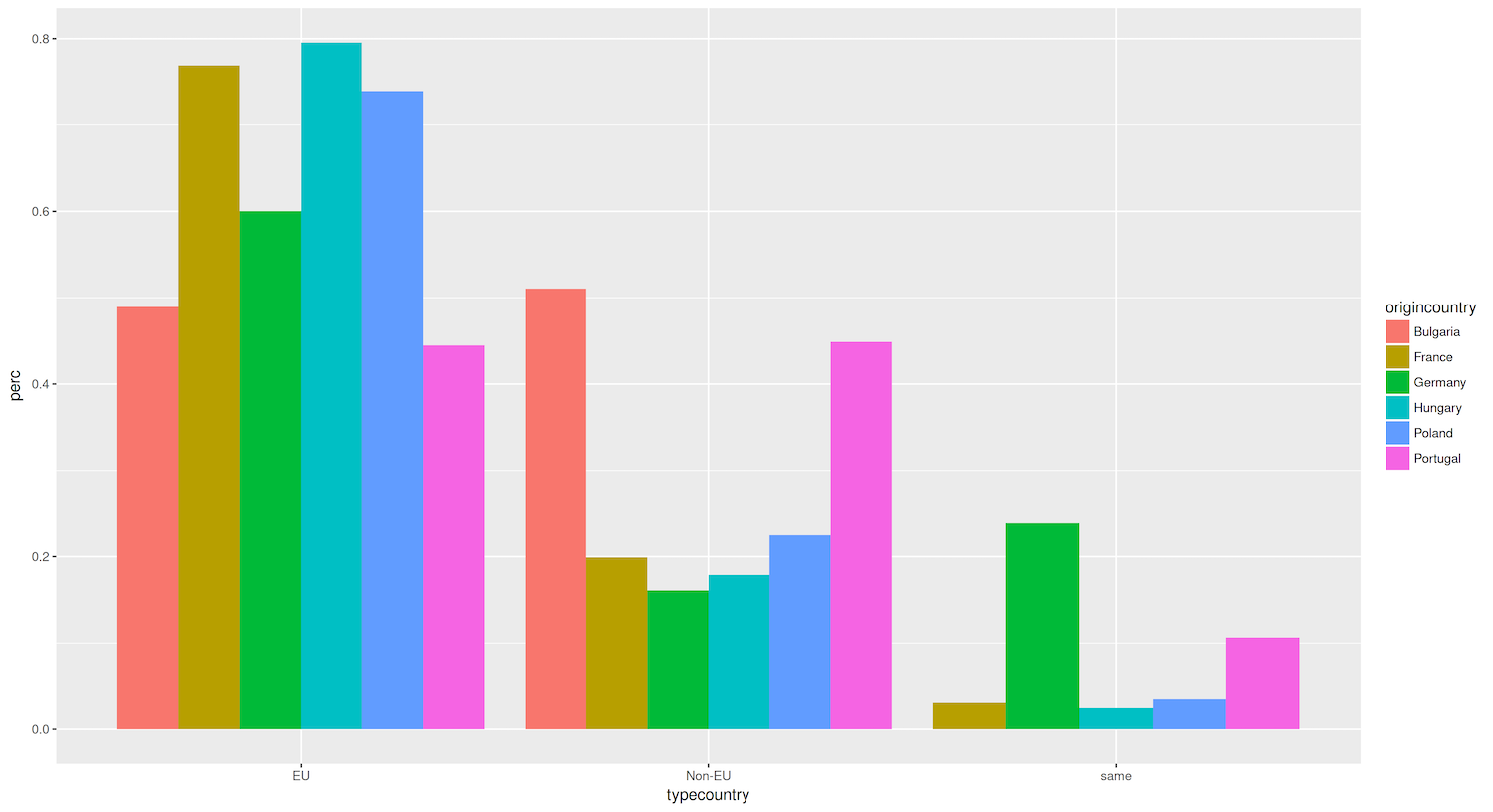

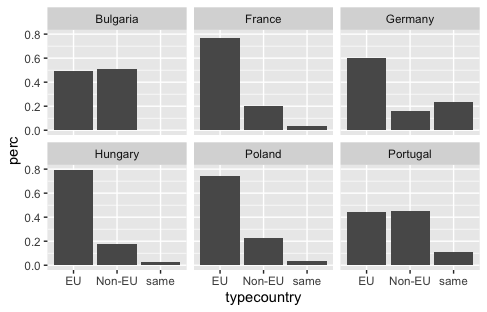

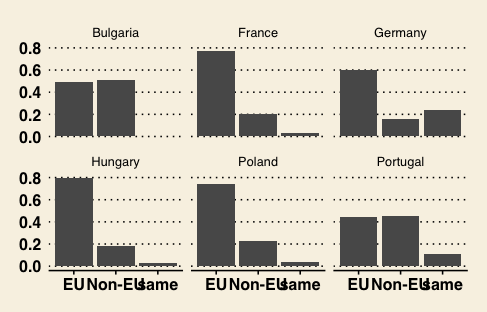

We see that most sister cities are in the EU. This could be due to geographical proximity, cultural similarities, or economic ties within the European Union. To look into this more, we can compare the data by country of origin. Once we have calculated the percentages for each country, we can visualize it in two ways. One, we can create a a bar for every country. Two, we can make a separate graph for each country (‘facetting’ in ggplot2 parlance). For now, we will stick with the first approach.

# We aggregate the data per country and type of country and add a new column with percentages

eudata.perc.country <- eudata %>%

group_by(origincountry, typecountry) %>%

summarise(total = n()) %>%

mutate(perc = total/sum(total))

ggplot(data = eudata.perc.country, aes(x = typecountry, y = perc, fill = origincountry)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", position="dodge")

Figure 3. Bar graph showing the percentage of destination cities that are domestic, EU, and non-EU with aggregated data per country and type of country.

Again, we created a new tibble that contained data aggregating per country and destination city type (EU, non-EU, etc). We mapped the origincountry column to the fill aesthetic in the ggplot() command, which defines the color range of the bars. We also added the parameter position to geom_bar() so that the bars do not get stacked (which is the default) but are instead placed side by side. Again, ggplot2 has chosen sensible defaults regarding colors and legend placement.

Now that we have visualized the data, we can analyze the patterns and draw insights from the graph. The bar plot reveals that the majority of the countries in our analysis, such as Germany, France, and Hungary, strongly prefer to establish sister city relationships with other European Union countries. Approximately 70-80% of their partnerships are with cities in the EU.

However, two countries stand out as exceptions: Bulgaria and Portugal. The proportion of sister city relationships with EU and non-EU countries is roughly equal for these countries. This suggests that Bulgaria and Portugal have a more balanced approach to forming partnerships that involve actively engaging with cities outside the European Union.

In the case of Portugal, this more global outlook might be attributed to its colonial history. Portugal’s extensive colonial past may have fostered long-lasting cultural, linguistic, and economic ties with cities in its former colonies, such as those in Brazil, Angola, and Mozambique. These historical connections could explain Portugal’s higher proportion of sister city relationships with non-EU countries than other European nations.

As for Bulgaria, further investigation is needed to uncover the factors contributing to its relatively high percentage of non-EU sister city partnerships. Possible explanations could include its geographic location at the edge of the European Union, its cultural and linguistic ties to countries in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, or its economic relationships with countries outside the EU.

While these initial observations provide a starting point for understanding the patterns of sister-city relationships, it is essential to delve deeper into each country’s historical, cultural, and political context to fully comprehend the underlying reasons for these trends.

Other Geoms: Histograms, Distribution Plots and Boxplots

We have seen the key syntax needed to operate ggplot2: adding layers and parameters to those layers. One of the most important layers is the geoms. Using this layer is straightforward in ggplot2: every plot type has a geom that can be added to ggplot(). For histograms, we have geom_histogram(), for boxplots geom_boxplot(), for violin plots geom_violin(), for dotplots geom_dotplot(), for scatterplot geom_point(), and so on. Every command has parameters that let us configure aspects of the geom(), such as size and color.

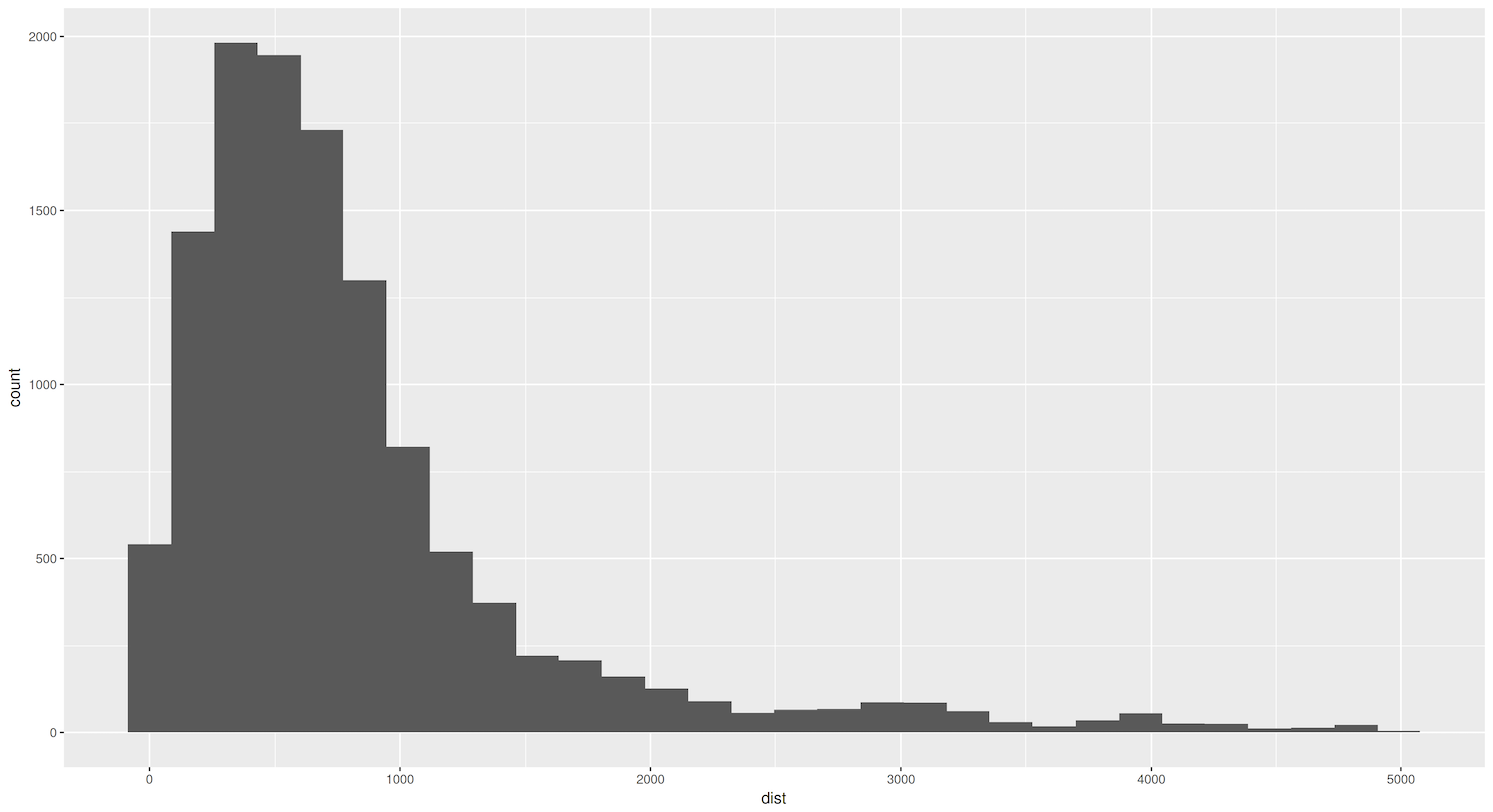

To get practice with these geoms, let’s create a histogram to visualize the distribution of the variable dist in our data, which represents the distance in kilometers between all of our sister cities.

# Filter the data and visualize it

# Load tidyverse or dplyr, otherwise filter will throw an error!

eudata.filtered <- filter(eudata, dist < 5000)

ggplot(eudata.filtered, aes(x=dist)) + geom_histogram()

Figure 4. Histogram showing distances (in log10) between sister cities.

As you see, we only needed to add the layer geom_histogram() to create a histogram. However, making a good histogram involves determining a bin size that makes sense for the data. The bin size, also known as the interval or bandwidth, refers to the width of each bar in the histogram. It determines how the data is grouped and displayed. In the example histogram we created, ggplot2 displays a warning that it has defaulted our binwidth to 30 (bins=30) and recommends picking a better value with binwidth. This suggests that the default bin size chosen by ggplot2 may not be optimal for our data, and we should consider adjusting it to create a more informative and meaningful histogram. Explore the help page of geom_histogram() to look at more configuration possibilities.

However, even with this initial graph though, we can see that the distribution of the variable dist is skewed with only a few cities far away. The skewness of the dist variable has important implications for our analysis. It suggests that while most sister cities tend to be geographically close, there are notable exceptions where cities establish partnerships with far-off counterparts. To understand why this is the case, we need further investigation. For instance, we could look into the specific characteristics of the cities involved in these long-distance partnerships, exploring the historical and contemporary contexts that have shaped these connections, and comparing them to the more common short-distance relationships.

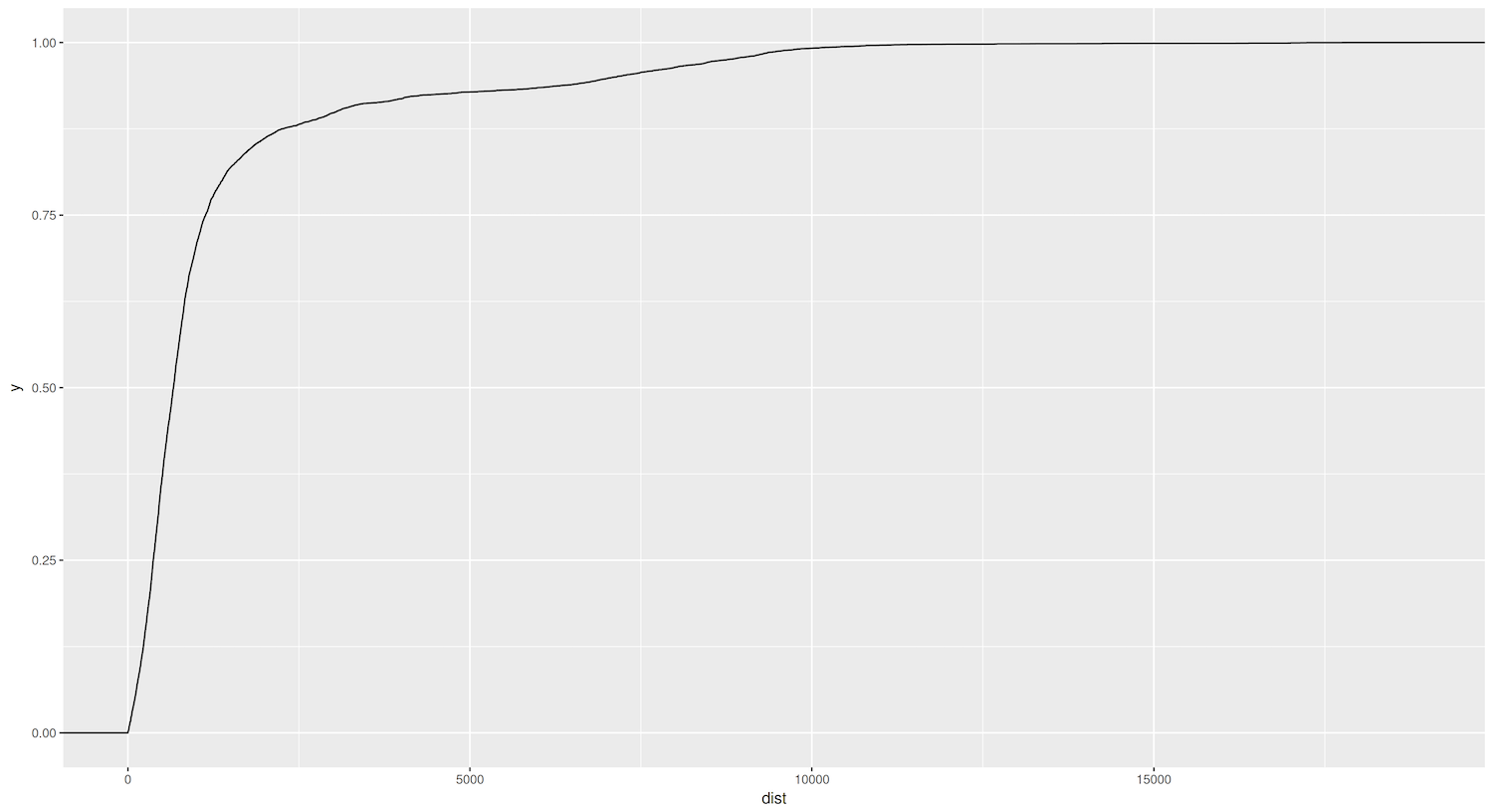

We can use a cumulative distribution function (ECDF) to gain additional insights into the distribution of the dist variable and help us better understand the skewness we observed in the histogram. This type of plot shows the proportion of data points that are less than or equal to a given value—in other words, the cumulative probability distribution of a variable. Through this, we can better understand the proportion of sister cities that fall within specific distance ranges. For example, we can easily determine the percentage of sister cities located within 1000 kilometers of each other or identify the median distance between sister cities.

The ECDF can also help us assess whether the skewness we observed in the histogram is a genuine feature of the data or a result of the chosen bin size. If the ECDF shows a similar pattern of skewness, with a steep increase on the left side and a more gradual increase on the right, it would confirm that the skewness is an inherent characteristic of the dist variable. In ggplot2, we can create an ECDF by adding the stat_ecdf() layer to our plot. Here’s an example:

ggplot(eudata.filtered, aes(x=dist)) + stat_ecdf()

Figure 5. ECDF Graph showing the distances between sister cities.

Let’s examine the ECDF plot we created using the unfiltered eudata data frame. The plot confirms our previous observation about the skewed distribution of distances between sister cities. Approximately 75% of the cities have sister-city relationships within a radius of around 1000 kilometers. This finding reinforces that geographic proximity plays a significant role in forming sister-city partnerships. Even more intriguing is that roughly 50% of the cities appear to be connected to sister cities that are no more than 500 kilometers away.

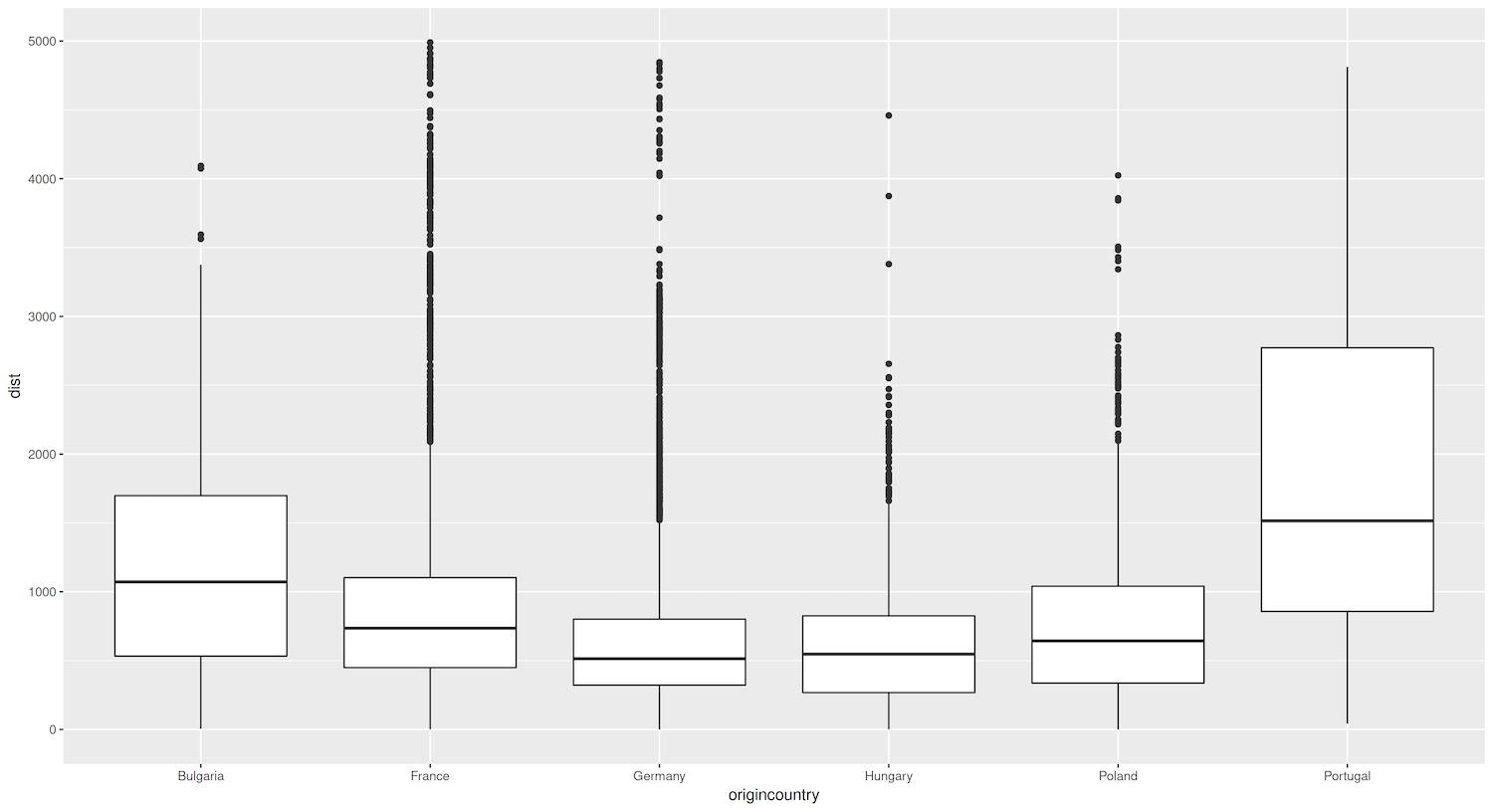

Lastly, we can create a boxplot to compare the distribution of distances between sister cities across different countries. We can then easily identify differences in the median distances, the spread of the data, and the presence of outliers for each country. For example, if we observe that the boxplot for a particular country has a higher median distance and a larger spread than other countries, it would suggest that cities in that country are more likely to form partnerships with distant cities than others. On the other hand, if a country’s boxplot shows a lower median distance and a smaller spread, it would indicate a tendency for cities in that country to establish relationships with closer cities than others.

ggplot(eudata.filtered, aes(x = origincountry, y = dist)) + geom_boxplot()

Figure 6. Boxplots showing distances (in km) between sister cities of different countries.

The boxplot comparing the distances between sister cities across different countries reveals an interesting pattern for German cities. The plot shows that German cities tend to establish sister-city relationships with cities that are geographically closer to them, as indicated by the lower median distance and smaller spread of the boxplot for Germany compared to other countries. This could reflect Germany’s position as a central and well-connected country within Europe. Germany’s geographic location and strong economic ties with its neighbors could facilitate the formation of regional partnerships and encourage cities to seek out connections within a smaller radius.

Advanced Manipulations Regarding the Look of Graphs

We played with different geoms, but we often relied on decisions ggplot2 made regarding the look of the graph. However, we often want to change this for various reasons, such as improving readability, highlighting specific aspects of the data, or adhering to specific style guidelines. ggplot2 offers a wide range of customization options to fine-tune the appearance of our plots. To see how we can do this, we will start with a simple plot and build on it step by step.

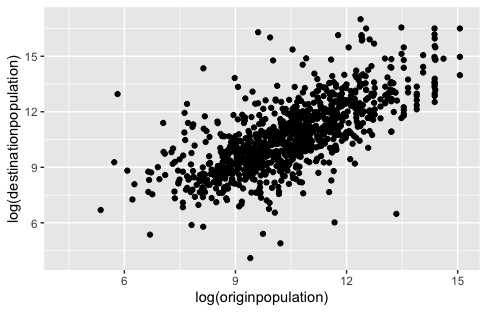

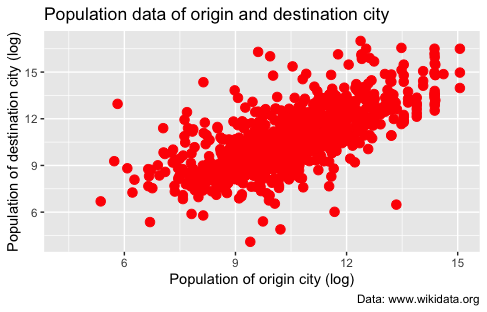

Let’s explore the relationship between the populations of sister cities. Our dataset includes information on the population of both the origin and destination cities for each sister-city pair. This raises an interesting question: Is population a related variable in sister-city relationships? In other words, do smaller cities tend to form partnerships with other small cities, while larger cities are more likely to connect with other large cities?

To investigate this question, we can create a scatterplot that visualizes the population data for the origin and destination cities. A scatterplot is a graph that uses dots or points to represent the values of two variables for each observation in a dataset. In this case, each point on the scatterplot will represent a sister city pair, with the x-coordinate indicating the population of the origin city and the y-coordinate representing the population of the destination city. By examining the pattern of points on the scatterplot, we can gain insights into the relationship between the populations of sister cities. If we observe a clear positive trend, with points clustering along a diagonal line from the bottom left to the top right of the plot, it suggests that cities with similar population sizes form sister-city relationships.

Since the data frame eudata has many points, this could lead to overplotting. Therefore, we will a random sample of 15% of the cities in our dataframe with the function sample_frac(). We also use the natural log of the population data to overcome skewness.

Since we are looking at a random selection of the data, we need to set a seed to ensure reproducibility. We can do this with the set.seed() function. Thus, if you run the code again, you will get the same random sample.

# Set seed to assure reproducibility

set.seed(123)

# We extract a random sample of 15% of the cities

eudata.sample <- sample_frac(eudata, 0.15)

# we create the plot

ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point()

Figure 7. Scatterplot displaying the relationship of the population (in log10) in the sister cities that were randomly selected.

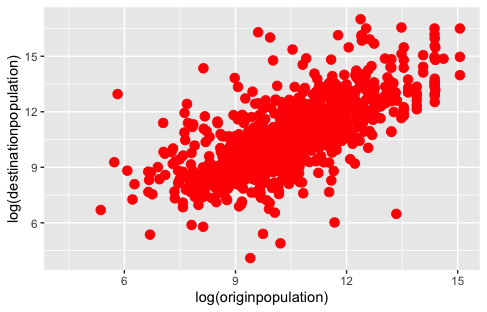

Now that we have created a basic plot, we can explore how to change its look. We will begin by changing the size and color of the points to have static values. We could also map a column, allowing them to vary based on the data.

ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point(size = 3, color = "red")

Figure 8. Changing the size and color of the points of a scatterplot.

As you can see, we passed the function geom_point() different arguments (size and color/colour). To find out other arguments that are available, you can visit the help page of geom_point() by typing ?geom_point in R or here online.

The plot looks a bit better, but many things remain to improve. For instance, we can add titles to the axes. Manipulating axes (and legends) is done by using the corresponding scales functions, which we will cover later on. But since changing the titles is a very common action, ggplot has a shorter command to achieve it: labs() (which stands for labels):

ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point(size = 3, color = "red") +

labs(title = "Population data of origin and destination city",

caption = "Data: www.wikidata.org",

x = "Population of origin city (log)",

y = "Population of destination city (log)")

Figure 9. Adding titles and caption with labs().

Now that we are happy with our graph, we can save it:

ggsave("eudata.png")

# for getting a pdf

# ggsave("eudata.pdf")

This will create a .png file with the last plot we have constructed. The function ggsave() has many parameters you can also adjust if needed (dpi, height, width, format, etc.).

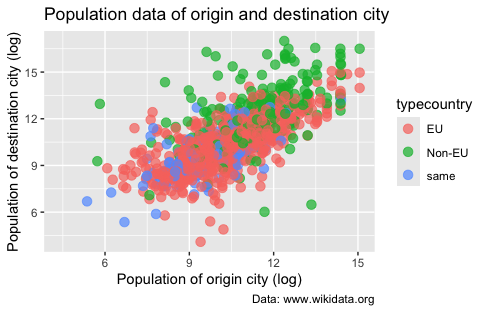

Sometimes, we may want to enhance our graph by encoding additional information using different colors or shapes. This is particularly useful when we have categorical variables in our data that we want to visualize alongside the main variables of interest. In the previous scatterplot example, we used static values for the size and color of the points. However, we can map these aesthetic properties to specific columns in our data to represent different categories.

For instance, let’s say we want to color the points in our scatterplot to distinguish between different types of sister city relationships based on the location of the destination city. Our dataset has a categorical variable called typecountry that indicates whether the destination city is in the same country as the origin city, in another EU country, or in a non-EU country. To incorporate this information into our scatterplot, we can map the typecountry variable to the color aesthetic by passing the aes() function to geom_point():

ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = 0.7, aes( color = typecountry )) +

labs(title = "Population data of origin and destination city",

caption = "Data: www.wikidata.org",

x = "Population of origin city (log)",

y = "Population of destination city (log)")

Figure 10. Using colors in scatterplots for showing different countries.

Above, we did two major manipulations to this plot. First, we modified geom_point() by adding an argument: aes(color = typecountry). Since there are too many points, we added the parameter alpha to make them transparent. Again, ggplot2 has selected sensible default colors and legends for the graph.

Scales: Colors, Legends, and Axes

It’s time to look at the scales function in ggplot2. Scales play a crucial role in determining how data values are mapped to a plot’s visual properties. They control data transformation into position, size, color, and shape aesthetics. Additionally, scales define how these aesthetics are displayed on the plot, including the range of values, the breaks or tick marks, and the labels.

In ggplot2, scales follow a naming convention that consists of three parts separated by underscores:

-

The prefix “scale”.

-

The name of the aesthetic being modified (e.g., color, shape, x, y).

-

The type of scale being applied (e.g., continuous, discrete, brewer).

For example, scale_color_continuous() is used to control the color aesthetic with a continuous scale, while scale_shape_discrete() is used to modify the shape aesthetic with a discrete scale.

One common use of scales is to change the colors of our plots. We can manually specify colors using specific color values or predefined color scales. Let’s first store our previous plot in a variable to demonstrate this. This is a convenient way to create different versions of the same plot by modifying only certain aspects.

p1 <- ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = 0.7, aes( color = typecountry )) +

labs(title = "Population data of origin and destination city",

caption = "Data: www.wikidata.org",

x = "Population of origin city (log)",

y = "Population of destination city (log)")

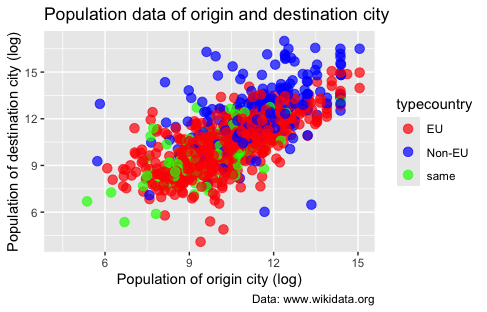

Now that we have stored the plot in the variable p1, we can easily modify the color scale. To manually specify colors, we can use the scale_color_manual() function and provide a vector of color values. In this case, we will use colors that R has already defined. We could also use hexadecimal codes for specific colors. As you see, scale_colour_manual() takes a compulsory argument (values =), namely a vector with the names of colors.

p1 + scale_colour_manual(values = c("red", "blue", "green"))

Figure 11. Using scale_colour_manual() to change the colors of the scatterplot points.

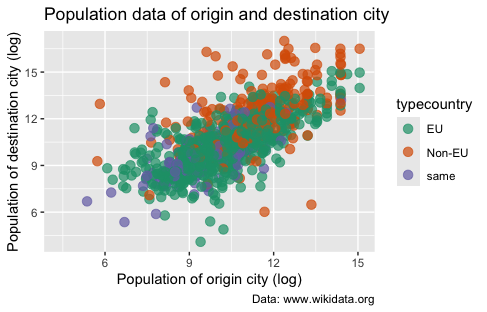

In this way, we can create graphs with our preferred colors. But, it is better to use already defined color scales when possible, such as the color brewer palettes. ggplot2 has already these palettes integrated and a specific scale for using them (scale_colour_brewer()):

p1 + scale_colour_brewer(palette = "Dark2") # you can try others such as "Set1", "Accent", etc.

Figure 12. Using scale_colour_brewer() to change the colors of the scatterplot points.

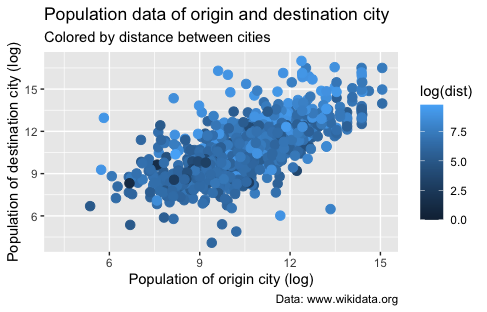

Let’s look at a slightly different example. In the last graph, we used a qualitative variable (typecountry) with different colors. But, what if we wanted to use a continuous variable? Let’s say we want to add information to our plot including the distance between the cities (we will again use the log of the distance because of skewness). We want to use the intensity of red to represent the distance:

p2 <- ggplot(data = eudata.sample,

aes(x = log(originpopulation),

y = log(destinationpopulation))) +

geom_point(size = 3, aes( color = log(dist) )) +

labs(title = "Population data of origin and destination city",

subtitle = "Colored by distance between cities",

caption = "Data: www.wikidata.org",

x = "Population of origin city (log)",

y = "Population of destination city (log)")

p2

Figure 13. Population data of origin and destination city colored by distance between cities.

As you can see, there are two problems with this graph:

- Blue is the color used instead of red, which is not what we intended.

- The scale is counterintuitive because smaller distances are represented by a darker blue, while we would expect shorter distances to be represented by lighter colors.

Using the appropriate scale function is crucial when working with different types of variables in ggplot2. It ensures that the visual representation of the data accurately reflects the nature of the variable and effectively communicates the intended information to the viewer.

In the previous example, we used a discrete color scale (scale_color_manual()) to assign distinct colors to each level of a qualitative variable. This approach works well when dealing with categorical or factor variables, where each value represents a separate category or group. By assigning a unique color to each level, we can clearly distinguish between different categories and highlight their differences or similarities. However, using a discrete color scale may not be the most appropriate choice when working with continuous variables, such as distance between cities. Continuous variables have a range of values that can take on any value within a certain interval. In such cases, using a gradient color scale is more suitable to represent the continuous nature of the data.

Gradient or continuous color scales assign colors to values based on a smooth transition between different hues or shades. This allows for a more accurate representation of the continuous variable, as the gradual color change corresponds to the change in the variable’s value. Using a gradient scale, we can visualize the distribution of values and identify patterns or trends in the data.

There are several methods for creating gradient scales in ggplot2. For our purpose, we will use the scale_colour_gradient() function. This allows us to specify the colors for the minimum and maximum values of the continuous variable, and ggplot2 automatically interpolates the colors for the intermediate values based on the chosen gradient.

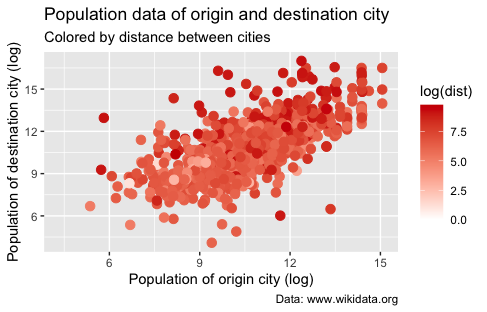

We can work with the p2 object created earlier and use the “+” operator to make modifications. We will map the dist variable, representing the distance between cities, to the color aesthetic using color = dist inside the aes() function. Next, we add the scale_colour_gradient() function to customize the color gradient. We specify low = "white" to set the color for the lowest values of the dist variable to white, and high = "red3" to set the color to a dark red for the highest values. This means that lighter shades of red will represent shorter distances, while darker shades of red will represent longer distances.

p2 + scale_colour_gradient(low = "white", high = "red3")

Figure 14. Population data of origin and destination city colored by distance between cities using scale_colour_gradient().

We can see that small cities tend to establish relationships with cities that are not so distant is an interesting finding related to the patterns we explored earlier in the article. In the previous sections, we examined the distribution of distances between sister cities using a histogram and an ECDF plot. These visualizations revealed that most sister-city relationships are characterized by relatively short distances, with a significant proportion of cities being connected to sister cities within a radius of 500 to 1000 kilometers. Consistent findings across different visualizations strengthen our confidence in the observed patterns. It highlights the importance of considering city size and distance as key variables in analyzing sister city networks.

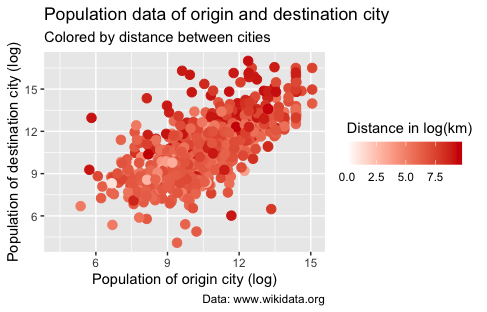

Building upon these insights, we will now focus on modifying the legend of our scatterplot. As mentioned earlier, the legend is controlled by the scales function in ggplot2. By customizing it, we can improve the interpretability and clarity of our visualization, making it easier for readers to understand the information being conveyed.

To modify the legend, we will use the guide parameter within the scale_colour_gradient() function. The guide parameter allows us to specify the appearance and behavior of the legend, such as its title, position, and orientation. In this case, we will use the guide_colorbar() function to create a color bar legend that represents the range of distances between sister cities.

p2 <- p2 + scale_colour_gradient(low = "white",

high = "red3",

guide = guide_colorbar(title = "Distance in log(km)",

direction = "horizontal",

title.position = "top"))

p2

Figure 15. Population data of origin and destination city colored by the distance between cities using scale_colour_gradient() and guide_colorbar().

In the provided code, we apply the scale_colour_gradient() function to the p2 object, which represents our scatterplot. The legend is controlled by the parameter guide. We tell ggplot2 to use a guide_colorbar() with the parameters for the title (caption, position, etc.).

Faceting a Graph

Previously, we created a plot that compared cities and their relationships with domestic cities in EU countries and non-EU countries using different colors for each country. ggplot2 allows you to split your data into different plots based on a variable. In ggplot2, this is called facetting. The simplest facetting function is facet_wrap(), but you can also look at the richer facet_grid() for more options.

Using our previous dataframe eudata.perc.country, we can facet our graphs by adding a facet_wrap() layer in the following way to get a different graph for each origin country:

ggplot(eudata.perc.country, aes(x = typecountry, y = perc)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~origincountry)

Figure 16. Facetting a graph with facet_wrap().

The formula ~origincountry tells ggplot2 to split the data based on the values of the origincountry variable and create a separate graph for each country. The resulting plot will display the bar graphs for each country in a grid layout. The tilde (~) operator is commonly used in R for formulas. In the context of facet_wrap(), however, it indicates that the variable should be used to define the faceting structure.

Themes: Changing Static Elements

Since modifying the appearance of graphs is a frequent task, ggplot2 also has themes. Themes are one of the most powerful and rich features of ggplot2, which makes it impossible to fully cover in this lesson. However, we will mention two aspects to get you started. First, ggplot2 comes with several built-in themes. The most common are theme_grey() (the default), theme_bw(), theme_dark(), and theme_void(). Second, you can easily create your own themes and use them in your plots.

Using a theme different from the default one is simple. We apply it as a new layer using the + operator:

p3 <- ggplot(eudata.perc.country, aes(x = typecountry, y = perc)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~origincountry)

p3 + theme_bw()

Figure 17. Changing static elements using themes().

Several packages add additional themes, such as ggthemes or ggtech. In these, you will find themes such as theme_excel (a theme replicating the classic charts in Excel) and theme_wsj (a theme based on the plots in The Wall Street Journal). Often, users believe that the “look” of a graph is more important than the data it represents. Consequently, they may try to make their graphs look like those in well-known publications. However, this is not always the best approach since the grammar of graphics specifies what elements of a graph are essential and how they map to data.

Thus, using themes from packages that consider this when changing features, such as through ggthemes is better. For instance, to mimic graphs created by The Wall Street Journal, we can do the following:

install.packages("ggthemes")

library(ggthemes)

p3 + theme_wsj()

Figure 18. Changing static elements using another theme (the Wall Street Journal theme).

Extending ggplot2 with Other Packages

One of the strengths of ggplot2 is the massive amount of extensions that the community has written. With them, you can create network graphs, radar charts, time series graphs, ridgeline plots, and many more.

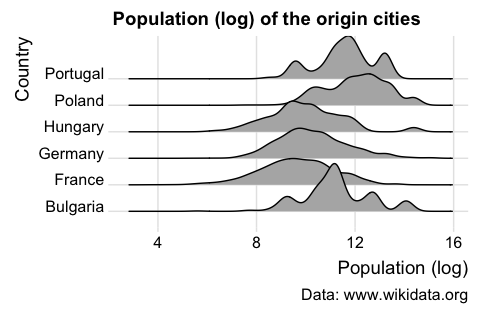

Let’s explore an example that showcases how ggplot2 can be extended using additional packages to create more advanced and visually striking plots. In this case, we will create a ridgeline plot, also known as a joy plot, designed to visualize changes in distributions over time or across different categories. Ridgeline plots are particularly effective for comparing multiple distributions in a compact and aesthetically pleasing manner, as they create the impression of a mountain range.

To create a ridgeline plot, we will leverage the capabilities of the ggridges package, which is an extension of ggplot2. This adds a new layer called geom_density_ridges() and a new theme theme_ridges(), which expands R’s plotting possibilities.

This code is simple enough (we use a log transformation due to the data’s skewness):

install.packages("ggridges")

library(ggridges)

ggplot(eudata, aes(x=log(originpopulation), y = origincountry)) +

geom_density_ridges() +

theme_ridges() +

labs(title = "Population (log) of the origin cities",

caption = "Data: www.wikidata.org",

x = "Population (log)",

y = "Country")

Figure 19. Extending ggplot2 with the package ggridges.

The graph shows that the population distributions of the origin cities vary across countries. The ridgeline plot reveals that some countries, such as Poland and Portugal, have origin cities with relatively large populations, as indicated by the peaks on the right side of their respective density curves. On the other hand, countries like Hungary and France have origin cities with smaller populations, resulting in density curves concentrated more towards the left side of the plot.

Conclusion

We have now explored the powerful capabilities of ggplot2 and its extensions for creating informative and visually appealing data visualizations. Throughout this tutorial, we have delved into various aspects of data visualization, from basic plotting techniques to advanced customization options. We have seen how ggplot2 provides a flexible and intuitive framework for creating a wide range of plots, including bar plots, histograms, box plots, scatter plots, and more, that enable us to communicate patterns, relationships, and insights effectively within our data.

Throughout this tutorial, we have worked with a dataset on sister cities, which has provided us with a rich and fascinating glimpse into the world of international municipal partnerships. By exploring this data using the tools and techniques of ggplot2, we have uncovered a range of insights and patterns that shed light on the nature and dynamics of these unique relationships. Our dataset has allowed us to investigate questions such as the geographical distribution of sister cities, the role of distance and population size in shaping these partnerships, and the prevalence of different types of relationships (domestic, EU, non-EU) across various countries. We have seen how cities tend to form partnerships with other cities that are relatively close in proximity, with a significant proportion of sister cities located within a 500-1000 km radius. We have also observed interesting variations across countries, with some exhibiting a stronger preference for domestic partnerships while others display a more balanced mix of EU and non-EU connections.

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg of ggplot2’s possibilities. With its extensive ecosystem of extensions and packages, ggplot2 offers endless opportunities for customization and adaptation to specific data visualization needs. Whether you’re working with time series data, network graphs, or geospatial information, there’s likely a ggplot2 extension that can help you create compelling and informative visualizations.

As you continue to explore and work with ggplot2, remember that effective data visualization is an iterative process that requires experimentation, refinement, and a keen understanding of your audience and communication goals. By mastering the principles and techniques covered in this tutorial, you will be well-equipped to create impactful visualizations that illuminate the stories hidden within your data.

Additional Resources

To gain a better understanding of ggplot2, We recommend you take a look at some of the following sources to gain a more thorough understanding:

-

The official Site for ggplot2.

-

Hadley Wickham’s books

ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis and R for Data Science. -

Hadley Wickham’s original paper on the grammar of graphics.

-

The original book by Leland Wilkson on the Grammar of Graphics.

-

Tutorial on r-statistics.co by Selva Prabhakaran.

-

Video by Data Science Dojo on an Introduction to Data Visualization with ggplot2.

-

UC Business Analytics R Programming Guide.

-

Official ggplot2 extensions page and accompanying gallery.

-

R Project’s overview of extending .

-

The documentation of the package provides a general overview.

-

The Cookbook for R book (based on the work R Graphics Cookbook. Practical Recipes for Visualizing Data by Winston Chang).

-

The R cheatsheet that you can find here.

-

To explore different gradient scales, see the following documentation page.