This is the draft website for Programming Historian lessons under review. Do not link to these pages.

For the published site, go to https://programminghistorian.org

Contents

- Introduction

- Data Collection

- Set Up your Coding Environment

- Data Preparation

- Modeling

- Visualization and Analysis

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Introduction

YouTube is the most popular web-based video sharing platform in the world, with billions of users viewing and uploading videos each month. This lesson will introduce readers to the way the comments written by users in response to viewing YouTube videos can be a valuable resource for researchers who are interested in analyzing discourse on the internet. This lesson is aimed at those who have a intermediate familiarity with the R programming language and experience conducting computational textual analysis.

In this lesson, you will learn how to download YouTube video comments and analyze the textual data using the natural language processing algorithm, Wordfish. Designed for scaling textual data using unsupervised machine learning, Wordfish brings into relief the salient dimensions of latent meaning within a corpus. Since Wordfish is useful for measuring ideological polarity in a set of documents, for this lesson’s sample dataset, we’ve collected comments submitted by viewers of Black Lives Matter videos posted in 2020 to YouTube by right- and left-leaning news sources in the United States as ranked by allsides.com.

This lesson will guide you through three key phases of 1) data collection, 2) data preparation (cleaning and modeling), and 3) data analysis (including generating visualizations).

First, this lesson overviews the preparatory steps for gathering data, including considering ethical issues related to downloading and analyzing YouTube data, as well as learning the basics of installing R and RStudio, and using the open-source YouTube Data Tools software. The Data Collection section then explains how to access and query YouTube’s Application Programming Interface (API) with the user-friendly YouTube Data Tools to download video metadata and comments. Readers will learn how to use YouTube Data Tools to search for and download video comments as tabular data (.csv file) for further manual or computational analysis with and beyond R.

Secondly, this lesson introduces how to use R to pre-process and clean YouTube comment data, as well as associated video metadata. YouTube user comments are ‘noisy’, often containing unusual content, like numbers, emojis, and URLs, which can negatively impact accurate text analyses.

Thirdly, this lesson will teach you how to model YouTube comment data with the Wordfish algorithm, using Ken Benoit’s quanteda R package. The Modeling and Visualization sections demonstrate how to analyze and interpret the comment data in R using Wordfish.

YouTube and Scholarly Research

While YouTube has often been associated with entertainment, it is also a virtual space where significant debates – explicit and implicit – about the significance of current events play out between politically and socially diverse YouTube viewers. The multimedia platform houses a wealth of culturally-relevant data that researchers and academics have only begun to explore.

Built into YouTube’s structure as a video sharing platform is a discussion space for extensive user comments and conversation. While YouTube comments often take the form of short responses to the video and to other comments, their content and purpose can vary widely. These comments frequently reveal ideological leanings, elicited by the commenter’s reaction to viewing a specific video, or by seeing another viewer’s comment in response to a video.

Scholarship on YouTube’s political dimensions has explored the complicated problem of untangling the effect of videos on viewer beliefs and perspectives. For example, qualitative sociological studies of YouTube users have explored whether users were radicalized through use of the platform.1 Other studies tackle its effects on political beliefs and engagement.2 While causation can be difficult to measure, YouTube video comments represent a unique corpus of textual discourse useful for wide-ranging research on how viewers receive and perceive politically charged messages from moving image media.

Youtube videos, including their titles and related metadata, incite a reaction in viewers, where discussions and replies play out often for tens of thousands of comments. These comments can frame subsequent viewers’ encounters with the video content, influencing their thoughts, and prompting them to share their interpretations in a reply or new comment, even years after a video has been posted. This means that while the dialogue between comments may represent an immediate back-and-forth between individuals, it can also involve extended hiatus and reactivation of discussion between a different group of participants. For this reason, some researchers focus specifically on conversational interplay in YouTube comments.3

For the purposes of this lesson, we’ll analyze a sample dataset to find broad discursive patterns and features, exploring ideologically salient topics rather than the minutaie of individual interactions across time. Readers might consider additionally exploring the temporal dimensions of their own corpus when building upon the methodologies presented in this lesson.4

Figure 1. Screenshot of YouTube website featuring video about debates over defunding the police in the United States

Learning Outcomes

This lesson explains how to use the R programming language to analyze YouTube video comments and related video metadata. To acquire the YouTube comment data, academic researchers have the option to access the YouTube API directly through the YouTube Researcher Program. For this lesson, you will learn how to use a web-based, API-querying tool,YouTube Data Tools, that does not require the creation of a researcher account.

This lesson will show how to use the YouTube Data Tool to download video comments and metadata, and then how to code in R to sort and clean the comment data, before analyzing with R the videos’ comment data for underlying meanings and ideological bent. Textual data collected with YouTube Data Tools can be further analyzed manually or computationally in many additional ways.

For analyzing and visualizing YouTube comment data, this lesson will teach you how to use the R programming language with Wordfish. A text analysis algorithm frequently employed by political scientists, Wordfish can demonstrate one compelling example of how YouTube comment data can be analyzed computationally to understand underlying discursive trends. For research purposes, Wordfish is well-suited to identifying, for example, political actors’ latent positions from texts that they produce, such as political speeches. When Wordfish analysis has been performed on documents whose primary dimension relates to political issues with clear binary oppositions, scholars have successfully shown the results to reflect the Left-Right scale of political ideology.5

Data Collection

Ethical Considerations for Social Media Analysis

Before we begin, it is important to consider the many ethical issues that arise in projects that collect and analyze social media data, as D’Ignazio and Klein argue in Data Feminism. Researchers should consider ethical questions at the start of their research.

One issue to consider is whether public social media data should be used for research without content creators’ permission. A user who comments on a number of related videos may not have understood that their patterns of communication would become the subject of scrutiny by political scientist and evidence in public debates over the effects of social media. While general recommendations can be difficult to make for social media research, to address the issue of privacy, for this lesson, we chose to anonymize user information when downloading comments, as described in the Downloading Comments and Metadata section.

How does researching a group of users with whom the researcher is less culturally familiar risk causing unintentional harm? Who speaks for communities being researched online? There are no clear answers to these challenging questions, but researchers should consider carefully their own cultural context and limitations in interpreting discourse from other cultures and contexts. Incorporate ethical thinking into the development of your research and code is essential to creating impactful public scholarship: not everything that could be mined, analyzed, published, and visualized from YouTube should be.

There are a variety of resources that can help researchers think through such ethical issues. The University of California at Berkeley hosted a conference on ethical and legal topics in June 2020, recorded in the open access book Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining. Review also the LLTDM website, as well as the Association of Internet Researcher’s Ethics page and Annette Markham’s Impact Model for Ethics: Notes from a Talk.

Video Selection

The most direct way to select videos for research is to visit the YouTube website, search for videos that are of interest, and capture a list of video IDs. Video IDs are the set of alphanumeric characters that appear in the video’s URL, immediately after watch?v=.

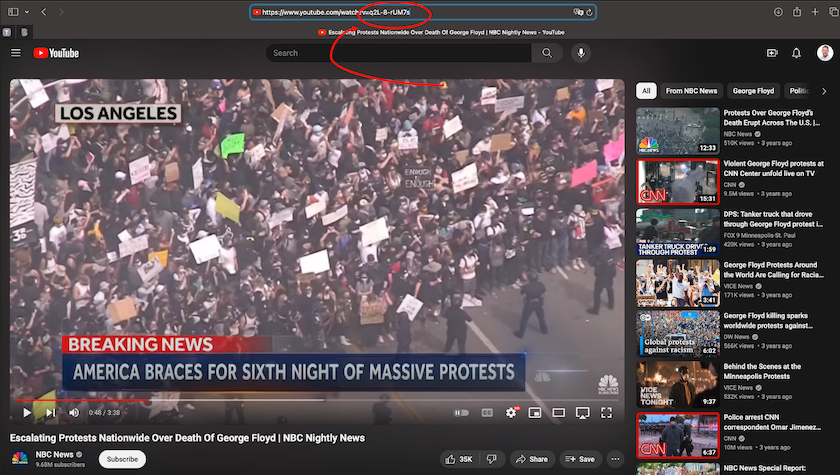

For example, see the video ID circled in red in the illustration below: q2l-8-rUM7s. These IDs are constant and do not change over time.

Figure 2. Screenshot of YouTube video with video ID in browser link circled in red

For this lesson, we gathered comment data by searching YouTube for ‘black lives matter george floyd’. We selected a total of six videos from politically polarized news sources (as ranked by allsides.com in 2020), from the left-leaning (arguably centrist) New York Times, Vox, and NBC News, and the right-leaning Daily Mail, Fox News, and the Daily Wire. Choosing multiple videos is often the best approach for the exploratory stages of research, because while YouTube makes available a wide range of metadata about each video (number of likes, title, description, tags and more), the YouTube API may not consistently return comprehensive comment data for every video searched.

For following along with this lesson, you may prefer to simply download the sample dataset and focus on the analysis stage. In this case, you can skip the next two sections and go directly to Setting Up your Coding Environment. This sample dataset was gathered using YouTube Data Tools; you can download it yourself using the same video IDs for YouTube Data Tools, but please note the data would likely differ based on the time you capture the data. In addition, user information was pseudonymized in this lesson’s sample dataset.

Curating Data for WordFish

When gathering YouTube comment data for building a Wordfish model, some considerations around the size and shape of the corpus should be taken into consideration. Curating a dataset of YouTube comments for Wordfish requires finding videos with a sufficient amount of data (enough comments, but also enough words per comment) to conduct predictive modeling. Before building the corpus, you also need to select the video comments to include in the analysis based on relevant metadata, like the video’s designated YouTube channel.

Wordfish modeling is typically performed on corpora with dozens or hundreds of documents, each usually containing hundreds or thousands of words. YouTube comments tend to be very short in length, but popular videos will often be accompanied by thousands of comments, more than enough to make up for their brevity. Ensuring the videos you select contain a substantial number of comments (~2000+) will minimize the skew that outlier comments can introduce. For the same reason, comments with less than ten words are also worth removing from the corpus.

For politically salient topics, an ideal dataset will include a similar number of videos from creators representing opposing political perspectives, and the video sources representing each side of the political spectrum should contribute a similar number of comments to the total corpus.

Querying YouTube’s API

We recommend using YouTube Data Tools to query YouTube’s API. YouTube Data Tools is developed by Bernhard Rieder, Associate Professor in Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam, and supported by the Dutch Platform Digitale Infrastructuur Social Science and Humanities. Rieder maintains and regularly updates the tool to ensure its continuing compatibility with YouTube’s API (for additional info, see the YouTube Data Tools Github repository. We’ve found YouTube Data Tools to be the best open-source and user-friendly tool available for acquiring YouTube data, because it uses pre-set credentials to access YouTube’s APIv3, saving you from registering your own Google account and keeping up to date on the newest API changes.

With YouTube Data Tools, you can use video IDs to pull video metadata and comments. You can also download other files, such as network diagrams of users, videos, and recommended videos. YouTube Data Tools outputs a neatly organized .csv spreadsheet of the downloaded comments alongside metadata about the exact time the comment was made, user information, and information about replies. Using this spreadsheet, a simple sort on the replyCount column can extract threaded conversations in order to focus on dialogue. The comments alone could also be concatenated into one large text file for topic modeling or other corpus analytics.

An alternative to YouTube Data Tools is to obtain YouTube API authorization credentials from Google so that you can query the API directly. This is a multi-step and somewhat complicated process, because the workflow can change each time Google issues updates. If you wish to query the API in R, you can try the tuber package and register for a Google developer account. While a developer account allows you to incorporate YouTube functionality into your own website or app, it can also be used simply to search and download YouTube content (see YouTube’s API reference page for more information). If you wish to participate in YouTube’s researcher program, there is a separate application process.

Downloading Comments and Metadata

Equipped with the video IDs for the videos you selected in the Video Selection phase, navigate to the Video Comments tab on the YouTube Data Tools site.

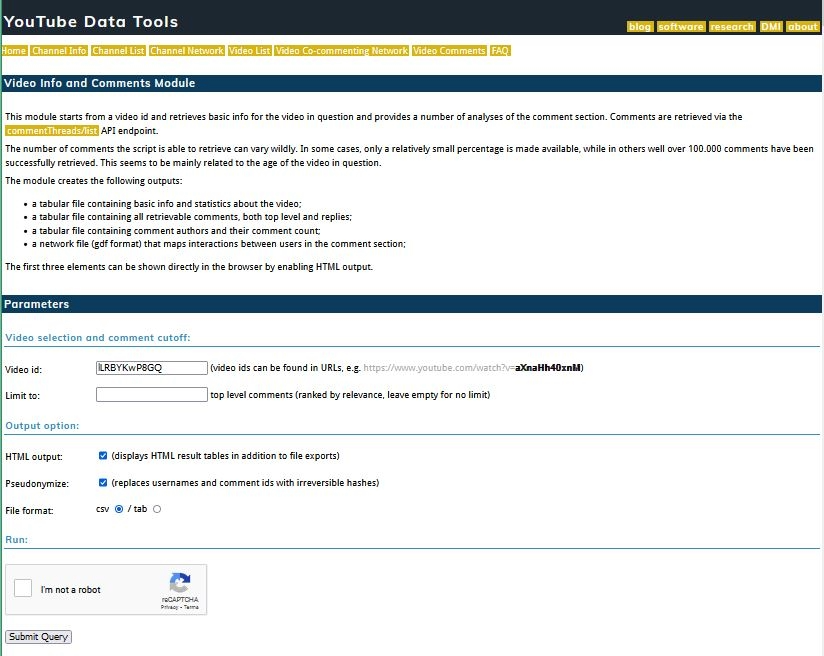

Figure 3. Screenshot of YouTube Data Tools webpage for downloading video comments

Enter the first video ID in the Video id field. You can only download comment data pertaining to one video id at a time.

For the Limit to field, we have left it blank, and would recommend doing so.

You have three choices to make about how your data output will be formatted.

First, for the HTML output parameter, check off the box if you’d like to generate HTML tables of your results in addition to file exports. This parameter gives you a preview of what you are downloading, which can be useful to monitor the downloading process.

Second, check off Pseudonymize to add irreversible hashes to the comment usernames and ID numbers, rendering them anonymous for the purposes of privacy mentioned in the Ethical Considerations section.

Thirdly, select .csv in the File Format parameter.

Finally, press Submit.

Repeat this process for each video. More details on this process can be found in Bernhard Reider’s instructional video.

YouTube Data Tools Output

Downloading data from the “Video Comments” tab on YouTube Data Tools will generate four files. Each automatically generated filename contains key pieces of information: the video ID, the download date, and a description of the file content.

Figure 4. The four files generated by YouTube Data Tools

The video ID follows immediately after the phrase “videoinfo.” In the image above, the video ID is highlighted in light blue. The download date (the date the files were generated and downloaded), immediately follows the video ID. We’ve highlighted it green in the above image.

The video ID and download date in the filename is particularly important to retain because new YouTube comments may continue to be uploaded after your data was initially collected. If you intend to publish findings related to the data you download, you will likely need to disclose your dates of collection.

Finally, you can discern what each file contains by looking at the end of the filename.

For each video ID you enter, YouTube Data Tools will download four files: 1) The first file, entitled “authors,” is a .csv file containing comment contributor names and their comment count for the selected video. 2) The second file, entitled “basicinfo,” is a .csv file containing basic metadata and statistics about the video. 3) The third file, entitled “commentnetwork” is a .gdf network file that maps interactions between users in the comment section and can be opened in software like Gephi (https://gephi.org/) 4) The fourth file, entitled “comments,” is a .csv file containing all retrievable comments, both top level and replies

Save the four files associated with each video into their own folder, using the corresponding video ID as the folder’s name. (As mentioned above, you won’t need all four files for this lesson, but they contain additional information that might be useful for further research.)

Next, create a master directory titled ytdt_data and save each of these folders inside. You will be using the ytdt_data folder in the code below.

Set Up your Coding Environment

Install R and RStudio

Once you have collected your data (or downloaded the sample dataset directly from this lesson’s /assets folder on the Programming Historian Github repository), the next step to text mining YouTube comment data is to prepare the R programming workspace. R is an open-source coding language with more available statistical algorithms than many proprietary softwares.

This lesson was written for R version 4.3.2 (but should work with newer versions). You can download R from the Comprehensive R Archive Network. Make sure you select the installer corresponding to your computer’s operating system – if needed, you can refer to Taryn Dewar’s lesson R Basics with Tabular Data, which covers how to install R and become familiar with it.

RStudio Desktop is the recommended integrated development environment for writing and running R scripts. The free version is more than sufficient. You can download and install RStudio from rstudio.com - again, make sure you select the installer appropriate to your computer’s operating system.6

The code used in this script includes packages and libraries from standard R as well as from the Tidyverse. Basic Text Processing in R by Taylor Arnold and Lauren Tilton provides an excellent overview of the knowledge of R required for text analysis. To learn more about Tidyverse, there are many great sources online, including A Tidyverse Cookbook by Garrett Grolemund.

The R script for this lesson and the sample data are available to download. The rest of this lesson will walk through the steps needed to create an R script from scratch, writing out each step of the same code we have made available for download. This lesson and the code can easily be adapted to alternative datasets downloaded through YouTube Data Tools.

Install R Environment and Libraries

To begin from scratch, you’ll create a new R script and install a series of packages.

Before installing the packages to clean and process the YouTube comments, we first install the renv package to set up a virtual enviroment for controlling versioning and dependencies, making R projects more reproducible. Because programming libraries are periodically updated, there is a risk that your code may no longer function as intended when a new package version is released. The renv package helps prevent this from happening by storing information about the versions of the packages used in a coding project along with the code. This is particularly useful when it’s necessary to use an older version of a package, as is currently the case for this lesson with the quanteda.textmodels package'. More details on renv and it's usefulness can be found in this [blogpost by Jan Bronicki](https://medium.com/codecurrent/revolutionize-your-r-projects-why-renv-might-be-the-solution-you-didnt-know-you-needed-ecf63464e02d) and the [renv` Github page](https://rstudio.github.io/renv/articles/renv.html).

To begin, we install and then initialize renv. Initializing renv directs RStudio to save the precise versions of the other packages you install. We have found that version 0.9.6 of quanteda.textmodels, the package we use to run the Wordfish model described later in the tutorial, performs best, so you use the renv::install function to install it here.

install.packages("renv")

renv::init()

renv::install("quanteda.textmodels@0.9.6")

You should double check the package versions and install specific versions using renv::install as illustrated above with the quanteda.textmodels package.

To install the necessary packages in R, run the following code:

install.packages(c("tidyverse", "quanteda", "quanteda.textmodels", "quanteda.textplots", "stringi"))

Note that if the code you run for this lesson runs into bugs, you should double check the package versions and install specific versions. We developed the code using the following versions of the necessary libraries:

tidyverse 2.0.0(containing necessary packagesggplot2,purrr,dplyr, as well aslubridate 1.9.3)quanteda 3.3.1quanteda.texmodels 0.9.6quanteda.textplots 0.94.3stringi 1.8.3

To load the packages necessary for data cleaning and wrangling into your R coding environment, run the following code:

library(tidyverse); library(lubridate); library(ggplot2); library(purrr); library(stringi); library(stringr)

Note that additional packages will be loaded into your working environment later in this lesson as necessary.7

Data Preparation

Now you can begin to explore the data you’ve downloaded. To read in a .csv of previously-downloaded comments and metadata, you can use the code supplied below. Just make sure your ytdt_data folder is in your R working environment.

The following code iteratively reads in all of the comment data from the comments.csv files in the ytdt_data folder, using the read_csv function from the tidyverse package.

comment_files <- list.files(path = "ytdt_data/",

recursive = TRUE,

pattern = "\\comments.csv$",

full.names = TRUE)

comment_files

all_comments <- read_csv(comment_files, id = "videoId", col_select = c(

commentId = id,

authorName,

commentText = text),

show_col_types = FALSE) %>%

suppressWarnings()

all_comments$videoId <- str_extract(

all_comments$videoId, "(?<=ytdt_data\\/).+(?=\\/videoinfo)"

)

all_comments

Next, read in the metadata from the basicinfo.csv files.

video_files <- list.files(path = "ytdt_data/",

recursive = TRUE,

pattern = "basicinfo\\.csv$",

full.names = TRUE)

video_files

Then pivot this data so it is organized by row rather than column:

all_videos <- read_csv(video_files, col_names = FALSE, id = "videoId", show_col_types = FALSE) %>%

mutate(videoId = str_extract(videoId, "(?<=ytdt_data\\/).+(?=\\/videoinfo)")) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = X1, values_from = X2) %>%

select(videoId, videoChannelTitle = channelTitle, videoTitle = title, commentCount)

Finally, run the following code to join the video metadata and comment text to create a single .csv:

all_data <- inner_join(all_comments, all_videos)

To see the number of comments per channel, use the count function as follows:

count(all_data, sort(videoChannelTitle))

Alternatively to downloading and integrating YouTube comment data, you could use any other corpus as the input data for this lesson’s analysis stages. However, you’ll first need to ensure your corpus is formatted the same way as described in this section by reordering and re-naming metadata as applicable.

Data Labeling

Now that you’ve imported and sorted your YouTube comment dataset, the next step is to classify the videos manually by adding a partisan indicator. Our case study project investigates comment discourse across left- and right-leaning video channels, so this partisan indicator allows us to later visualize and compare which video comments positioned on the ideological scale originated from the political affiliation of each video’s creator.

The code for creating an indicator is straightforward. Simply create a new column and then specify which video channels should be associated with each indicator value:

all_data$partisan <- all_data$videoChannelTitle

all_data <- all_data |>

mutate(partisan = as.factor(case_when(

partisan %in% c("Ben Shapiro", "New York Post", "Fox News", "DailyWire+") ~ "right",

partisan == "NBC News" ~ "left",

TRUE ~ partisan))

)

glimpse(all_data)

If you are using your own data, consider whether an indicator could be useful to help you visualize differences between groups of videos - such as videos from specific channels, or other logical groupings of videos based on theme or perspective.

Pre-processing

Now that the data is labeled, you are ready to pre-process and clean the comment data you’ve collected to make it suitable for text analysis with Wordfish.

As noted above, due to the unique properties of YouTube comments (such as rare words, slang, multiple languages, special characters, and emojis), some initial data cleaning is necessary to ensure that each comment contains enough meaningful text data for Wordfish scaling. Comments with little or no usable text data need to be removed, because they will cause substantial skew in a Wordfish model: the model relies on scores given to words within semantically meaningful prose, and comments with fewer than 10 words are less likely to contain such meaning. This can impact the significance of results, and may cause the scaling process to fail entirely.

If you are using an alternative analytical model, you may choose to retain emojis, links, numbers, mentions, or other details.

Remove Stopwords and Punctuation

The first pre-processing step is to remove stopwords, which are common words that provide little to no semantically meaningful information about your research question. As Emil Hvitfeldt and Julia Silge explain, whether commonly excluded words would provide meaningful information to your project depends upon your analytical task. For this reason, researchers should think carefully about which words to remove from their dataset.

During exploratory modeling, we found that the words ‘bronstein’, ‘derrick’ and ‘camry’ were outliers in our specific dataset, appearing at the lower left and right ends of the Wordfish distribution (which indicates those words are extremely rare in the overall corpus). When interpreting the horizontal scale created by the model, the most meaningful words to analyze are often the relatively common and highly polarizing words on each side of the distribution. Rare outlier words can often be a distraction; for this reason, you may wish to remove these outliers from the visualization.

The following code creates a custom stopword list that adds researcher-defined stopwords to the standard stopword list supplied in the quanteda computational text analysis package. To customize a stopwords list, simply replace the words in the code-chunk below with your own. As you conduct preliminary Wordfish modeling and exploratory analysis, if you come across obvious outlier words, we recommend you add these to your stopwords list.

library(quanteda)

my_stopwords <- c(stopwords("en"), "brostein", "derrick", "camry")

all_data$text <- all_data$commentText %>%

str_to_lower() %>%

str_remove_all(str_c("\\b", my_stopwords, "\\b", collapse = "|"))

Using the stringr package from the tidyverse, and the base R stringi library, the following code further cleans the text data. This additional pre-processing step takes a second swipe at removing any remaining numeric digits, punctuation, emojis, links, mentions, as well as comments with fewer than 10 total words. In addition, the following code removes duplicate comments and places the cleaned data into a column titled uniqueWords:

all_data$text <- all_data$text %>%

str_remove_all("[:punct:]||'|[$]") %>%

str_remove_all("[@][\\w_-]+|[#][\\w_-]+|http\\S+\\s*|<a href|<U[+][:alnum:]+>|[:digit:]*|<U+FFFD>")

all_data <- all_data %>% unique()

print(paste(nrow(all_data), "comments remaining"))

all_data$uniqueWords <- sapply(str_split(all_data$text, " "), function(x) paste(unique(x), collapse = " "))

all_data$uniqueWords <- sapply(str_split(all_data$text, " "), function(x) paste(unique(x), collapse = " "))

all_data <- all_data %>% mutate(

numbWords = str_count(all_data$uniqueWords, boundary("word"))) %>% filter(

numbWords >= 10)

print(paste(nrow(all_data), "comments remaining"))

Note you can also perform this step using the quanteda R package. We recommend stringr and stringi, especially if you want to export cleaned data to a user-readable format to perform other analyses beyond the Wordfish modeling demonstrated in the second half of this lesson. For further guidance on using the quanteda package, we recommend the University of Virginia Library’s useful overview of its functionalities, A Beginner’s Guide to Text Analysis with quanteda.

To export your cleaned data for preservation, curation, or other forms of analysis, use the write_csv function in R as follows:

write.csv(all_data, "cleaned_all_data.csv")

Now that the comment data is reduced to the essentials, you can transform the dataset into a format suited to Wordfish analysis.

Modeling

A wide range of text mining and machine learning algorithms are increasingly available for scholars looking to create models and visualizations of big data. Many of these algorithms have already been described in tutorials by Programming Historian - see, for example, word frequency analysis and topic modeling. The text mining algorithm we use in this lesson is called Wordfish. For information on the machine learning algorithm itself and to view Wordfish’s base code, see the Wordfish website and the Wordfish Github repository.

Developed by and for political scientists, Wordfish models textual data along a single-dimensional axis. It was created as a method for extracting the ideological leaning of documents expected to contain latent ideological and political perspectives (e.g., party manifestos, politician speeches). For example, Wordfish can be a useful tool for identifying whether United States representative floor speeches were made by Democrats or Republicans, as well as for measuring the extremity of the partisan leaning conveyed in those speeches.

Interpreting Wordfish

A Wordfish model uncovers two kinds of information, without the need for any prior pre-coding of documents or ‘supervision’.

First, Wordfish differentiates documents along a single dimensional scale. To do so, the model collects comments that are similar to each other from each end of the salient dimension, based on the kinds and frequencies of words appearing in the corpus. Documents on opposite ends of this scale, in particular types of discursive contexts, may be characterized by the inclusion of different sets of unique words, indicating a focus on different kinds of concepts.

Although Wordfish was initially developed by political scientists for researching political ideology, there is nothing inherently political about the dimension that it reveals: Wordfish can be used to extract latent dimensionality (based on broad differences in word usage) within any kind of corpus. There are many underlying factors that can drive the latent scaling dimension identified by a Wordfish model. If content is strongly motivated by the author’s political ideology, this dimension can separate texts from authors on opposing sides of a political issue. Wordfish brings into relief broad differences in content, based on the kinds of words used by each speaker. The substantive interpretation of this latent dimension depends entirely on what happens to be the most salient content in any given corpus.

Second, Wordfish develops a scale to describe the polarization of words within a corpus, and arranges those words along an analogous dimension to the document scale. Although the document scale is often the desired output of a Wordfish model, the placement of words along this scale is usually more informative than document scaling for understanding the overall meaning of the scale.

Scaling documents is less inherently meaningful without additional information. Metadata about the source of documents (in this lesson’s case, the partisanship of the video source) can be very helpful for determining whether the greatest differences exist within a given data source, or between data sources. For example, you might be able to see that comments from certain videos with shared perspectives are clustered together.

Document Feature Matrices (DFM)

Wordfish uses a Document Feature Matrix (DFM) to make its predictions about the placements of documents along this uni-dimensional scale.

A DFM is a tidy, structured format that stores data about the frequency of different words used in each document of a corpus. The ‘quanteda’ documentation includes guidelines on creating DFMs. Structured as a two-dimensional matrix with each document assigned a row, each column in a DFM designates textual ‘features’ (the words used across the vocabulary of the entire corpus). The cells in this matrix indicate whether a given feature appears in each document or not.

The DFM approach is similar to the tried and true text mining method known as topic modeling: both Wordish and topic modeling are machine learning algorithms that use predictive modeling to identify prevalent themes and perspectives in a corpus. Furthermore, both Wordfish and topic modeling involve ‘unsupervised’ methods: they don’t rely on the user pre-coding some portion of the data before modeling. Instead, these two algorithms both look at differences between documents, identifying natural groupings along a dimensional scale by comparing the frequencies of the same words between different documents. Both models identify and weigh more heavily words whose frequency varies most between documents, relying on these word patterns to cluster documents along the scale through an iterative process. When a Wordfish model is initialized, all of the parameters it measures are a ‘first best guess’ at the latent scaling of documents and words. Depending on the quality of the text data, these models refine their initial predictions, gradually closing in on more statistically robust and insightful model structures.

Another important similarity between Wordfish and topic modeling is that both treat any given document as a ‘bag of words’. The algorithms only look at word frequency, while ignoring word order: it doesn’t matter where words occur in any given document, just which words occur in that document, and with what frequency. Bag-of-words modeling can be problematic for longer texts where different sections of content (paragraphs, pages, chapters) might convey different types of meaning depending on their context. But YouTube video comments, and social media posts generally, tend to be short and frequently pertain to a single idea, so the bag-of-words approach is unlikely to miss as much information as would be lost for longer, more complex documents like essays or novels.

The key difference between Wordfish scaling and topic modeling, however, are the specific statistical approaches taken, and their most useful outputs. Whereas topic models can generate any number of topics in a corpus, Wordfish always scales on a single dimension and is thus limitied to two ‘topics,’ or a single topic as seen from two sides of a debate.

Create a Corpus in R

The Wordfish algorithm was initially distributed as a stand-alone R package (still available on the Wordfish website), but is now available in the quanteda package. The quanteda Wordfish package enables seamless wrangling of YouTube comment data into a useful format to build the Wordfish model. For documentation, visit Quanteda’s docs and tutorials page.

To run the Wordfish model in quanteda, you must create three types of text data objects: a corpus, tokens, and a DFM. For more detail on how these objects work together, see quanteda’s quick start page.

The corpus contains all of the documents that can be analyzed (in our case, each comment represents one document), as well as some metatdata describing the documents’ attributes. In our case, this metadata includes the video channel title with which the comment was associated, as well as the partisanship indicator added earlier in the Data Labeling section.

In quanteda, the tokens are a list of character vectors linked back to the document from which they originated. This form allows the text to be further cleaned and pre-processed. Tokens can be stemmed or lemmatized, and additional stopwords can be removed. You already pre-processed the corpus in the Pre-processing section, but the approach offered by quanteda works slightly differently, so you might wish to test which works best for you and your data; there’s no harm in using both cleaning methods.

Note that when running the code to build your corpus, the processing may take a few minutes, or even longer. If it does, that’s a good sign! It means your data is optimal for Wordfish modeling, and the model you produce will likely be insightful and accurate.

Select Comments

To initiate the steps leading to creating the Wordfish model itself, first select the specific columns that you would like to include in your model. The following code selects the comment text (the uniqueWords column), as well as the video channel title, the partisan indicator, and the unique commentId automatically generated by YouTube.

wfAll <- select(all_data, commentId, uniqueWords, videoChannelTitle, partisan, numbWords)

Build Corpus Object

Execute the following code to build your corpus:

options(width = 110)

corp_all <- corpus(wfAll, docid_field = "commentId", text_field = "uniqueWords")

summary(docvars(corp_all))

Data Transformation

Next, you will tokenize in order to create the DFM. You can use quanteda’s token function to remove any remaining punctuation, symbols, numbers, URLs, and separators. After this pre-preoccessing step, you’ll create a DFM and feed it into the Wordfish model.

toks_all <- tokens(corp_all,

remove_punct = TRUE,

remove_symbols = TRUE,

remove_numbers = TRUE,

remove_url = TRUE,

remove_separators = TRUE)

dfmat_all <- dfm(toks_all)

print(paste("you created", "a dfm with", ndoc(dfmat_all), "documents and", nfeat(dfmat_all), "features"))

Data Optimization

Now, we will optimize the corpus to focus on meaningful words only. The following code removes words with fewer than four characters, as well as rare words (those that appear in less than 1% of documents, or that comprise less than .001% of the total corpus).

dfmat_all <- dfm_keep(dfmat_all, min_nchar = 4)

dfmat_all <- dfm_trim(dfmat_all, min_docfreq = 0.01, min_termfreq = 0.0001, termfreq_type = "prop")

print(dfmat_all)

You may want to adjust these values to optimize the model for your own data. Consult the quanteda documentation on dfm_trim for additional optimization options.

Verification

After optimizing the corpus, it is helpful to manually review the 25 most frequently occurring words to get a sense of the comments’ overall meaning. If you notice words among the top 25 that have limited semantic meaning, consider adding them to your custom stopwords list, and running the code again.

The following lines of code print the 25 most frequent words for manual review:

topWords <- topfeatures(dfmat_all, 25, decreasing = TRUE) %>% names() %>% sort()

topWords

After fine-tuning the most 25 frequent words in the corpus, you can move onto creating the Wordfish model.

Build Wordfish Model

To create a Wordfish model based on the corpus of unique comments you have assembled, run the following code:

library(quanteda.textmodels)

tmod_wf_all <- textmodel_wordfish(dfmat_all, dispersion = "poisson", sparse = TRUE, residual_floor = 0.5, dir=c(2,1))

summary(tmod_wf_all)

Some computers may take a while to process the data when building the Wordfish model, depending on the number of documents in your corpus, and the number of times the model iterates. Remember: at this point, more iterations are a good sign, so be patient.

Visualization and Analysis

Now that the model is built, you can visualize its output. Wordfish models are well-suited for two distinct kinds of visualizations: a ‘document-level’ visualization and a ‘word level’ visualization, both of which are scaled along horizontal and vertical axes.

Slapin and Proksch (2008) first proposed the Wordfish model as an advancement over previous text-scaling methodologies.8 They use Wordfish to estimate the ideological positions of German political parties around the turn of the century.

The Wordfish model assigns two parameters to each word used in the corpus studied (beta and psi), and a similar two to each document (alpha and theta). The convention is to assign ideological polarity along the horizontal axis using the variables beta (for features) and theta (for documents). The vertical axis reflects a ‘fixed effect’ - psi (for features) and alpha (for documents). In ‘word level’ visualizations, the fixed effect psi is each word’s relative frequency, used to show dispersion across the corpus object. In ‘document level’ visualizations, the fixed effect alpha is a value representing the relative length of each document.

Very rare words and very short comments (documents) contain relatively little useful information, and their inclusion can be detrimental to the overall model. The preprocessing steps we share eliminate very short comments. However, you will likely see, and can confidently eliminate, additional highly infrequent words (those with very negative psi values) following initial model results.

Unique Words

The code in the this section will create ‘word level’ visualizations. To produce custom visualizations, we draw from Wordfish’s underlying statistics and use ggplot2 to make the plots. You can use Quanteda’s textplot_scale1d() function, setting the margin parameter to ‘features’. This function plays well with ggplot2, so you can use the ggplot2 ‘+’ to add components to the base plot. This lesson uses the labs() component to create a label for the plot.

Run the following code to produce a plot of all the unique comment words found within the corpus:

library(quanteda.textplots)

wf_feature_plot <- textplot_scale1d(tmod_wf_all, margin = "features") +

labs(title = "Wordfish Model Visualization - Feature Scaling")

wf_feature_plot

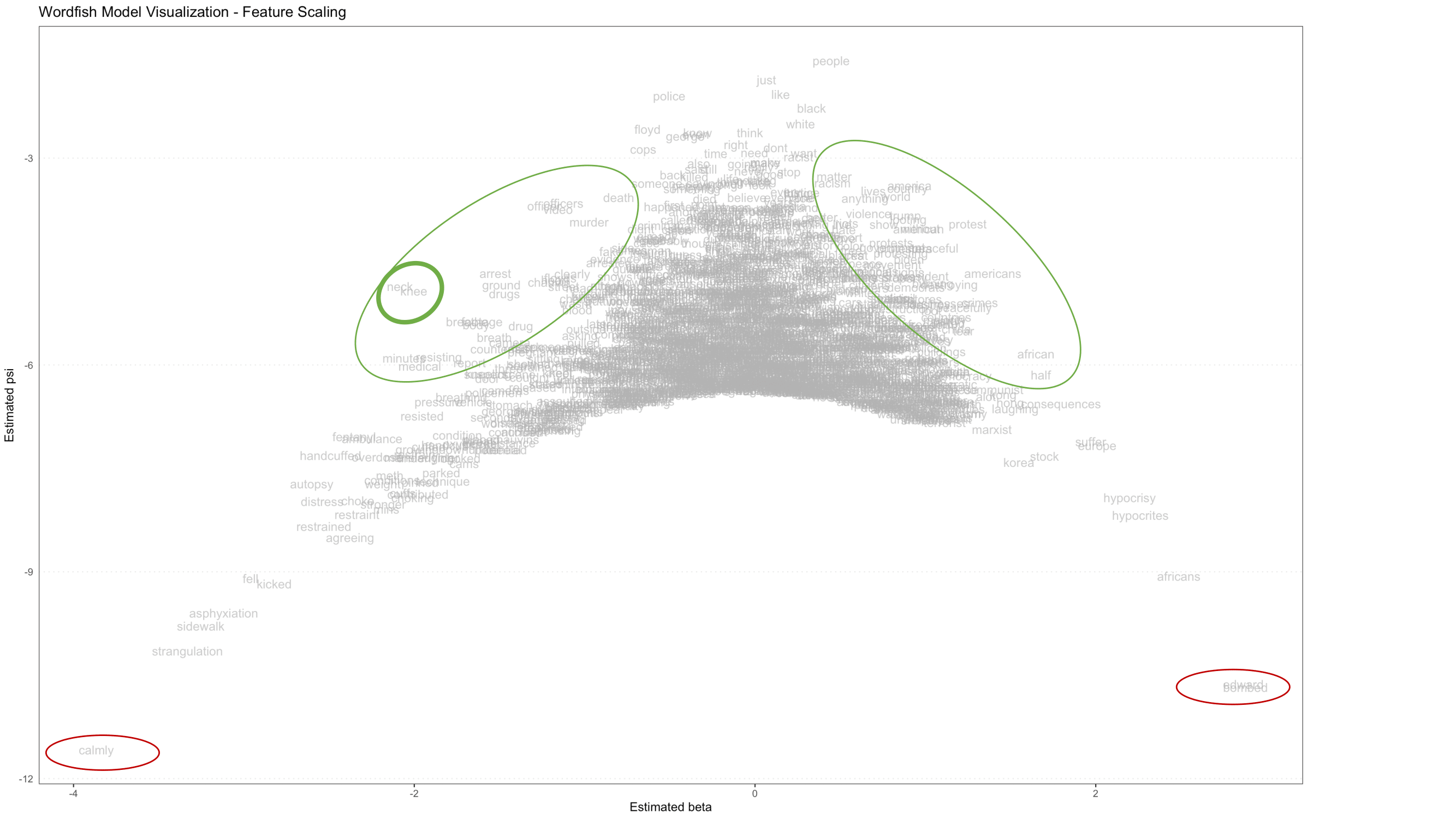

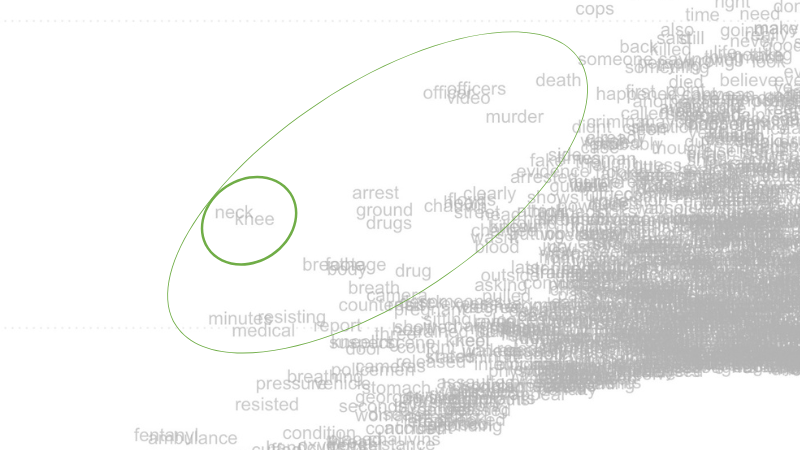

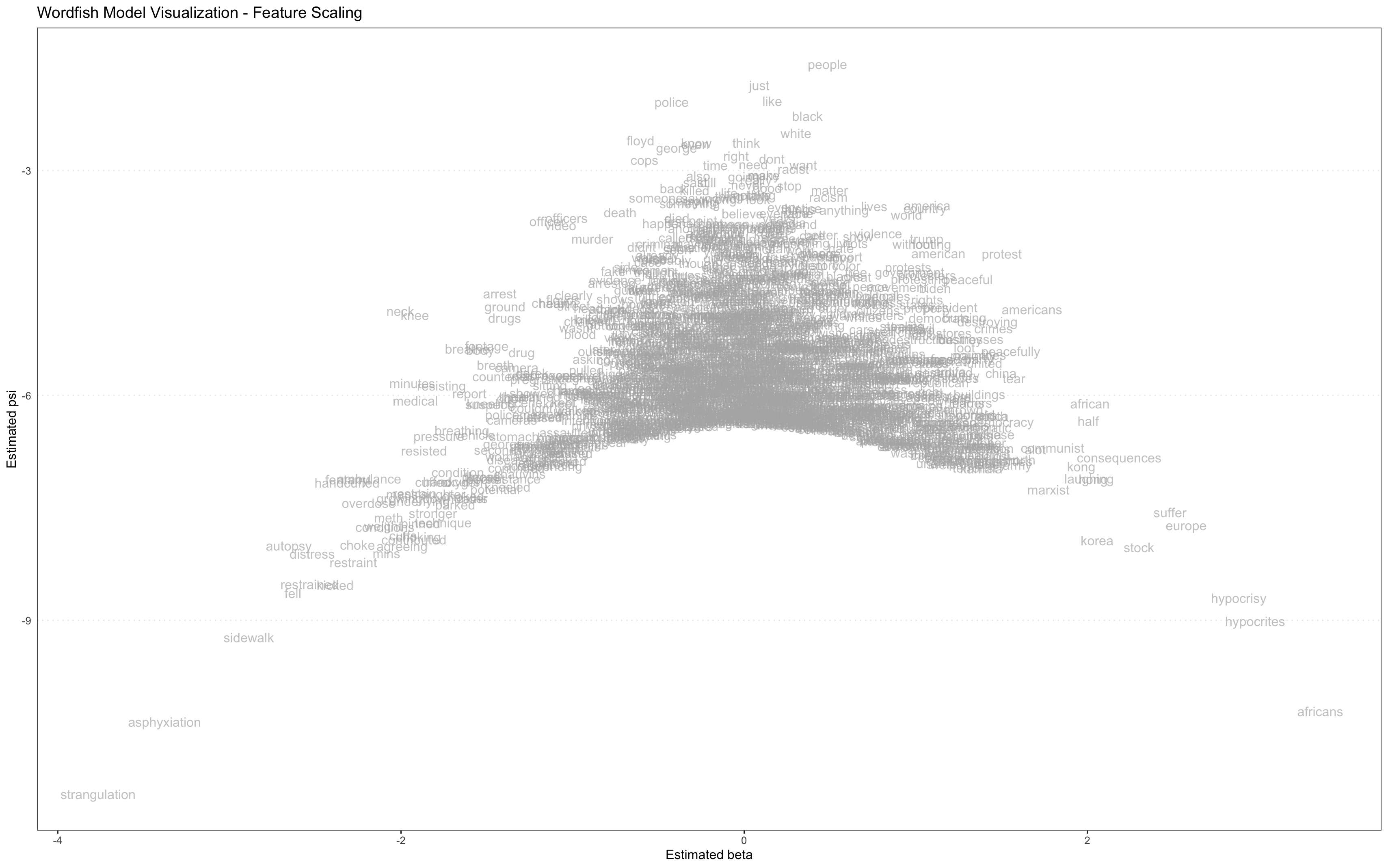

Figure 5. Visualization of Wordfish model showing relative placement of features (words) with significant words circled in green, and outliers circled in red

Figure 5 is a Wordfish model visualization of the feature scaling components, which shows every word found in the YouTube comment corpus. The position of each feature on this visualization is determined by two model outputs, beta and psi. The horizontal axis (beta) represents how extreme the scaling of each feature is: features far to the left and far right very strongly drive the placement of comments on the document left-right scale (which we’ll discover in the Analyzing the Visualization section below), while centrally located features have minimal impact. The vertical axis (psi) represents a fixed effect for each feature, describing how common that feature is: more common features appear at the top of the model, while rarer ones appear at the bottom. The model makes beta and psi interact in such a way that the scaling impact of common features is reduced (they are pulled to the top center) and the scaling impact of rare features is enhanced (they are pushed to the bottom horizontal extremes).

The features which are of intermediate frequency (appearing in approximate the middle of the vertical axis), and are highly polarizing (appearing further to the left or right than other features appearing with similar frequency), should most strongly guide the user’s interpretation of the model scale. The red circles in the far bottom corners of the visualization indicate features that are extremely rare, and likely don’t contribute much meaning to the model. These features can usually be safely removed, which will put more visual emphasis on more central - and therefore meaningful - portions of the model.

Note how the word distribution is roughly symmetrical, with most words grouped in the middle, and additional words projected out along the sloping sides of the inverted parabola (these words are indicated by the large green ovals drawn midway down the sloping sides). These conspicuously displayed words are the strongest indicators of what each pole of the scaled dimension (along the horizontal axis) represents.

On the left, knee and neck are displayed almost on top of each other (see the smaller, heavier weighted green circle in Figure 6 below). This indicates that those two words occur at the same frequency, and that both words are strongly and equally predictive of a document being placed on the left side of the scaling dimension. Given the subject matter of this dataset, this is an expected - if stark - result.

Figure 6. Close-up of left-hand portion of Wordfish feature-level visualization, displaying incident-related words that frequently co-occur, like ‘neck’ and ‘knee’.

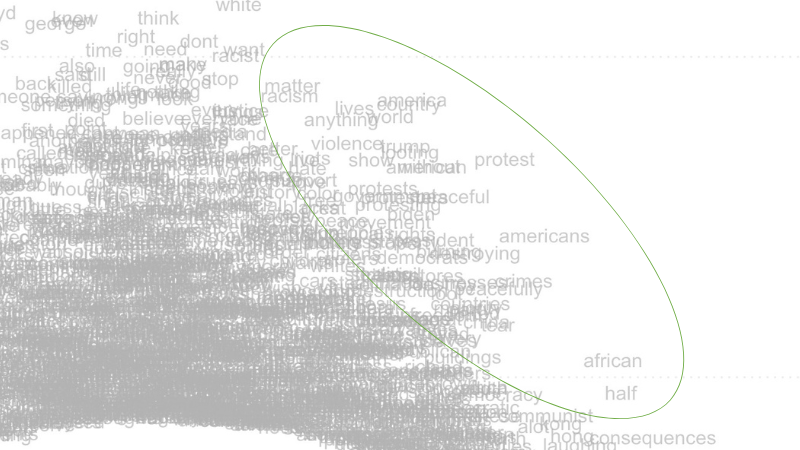

Along the right slope, note words like americans, protest, african and, a little deeper in the field of text, violence (see Figure 7 below). These words are predictive of a document being placed on the right pole of the scaling axis.

Figure 7. Close-up of right-hand portion of Wordfish feature-level visualization, displaying words that discuss the broader social context around George Floyd’s muder.

Words displayed on the left side of this data visualization refer more directly to the event of George Floyd’s murder itself, and may have been a stronger focal point for commenters identifying with the political left in the United States, which in 2020 was actively protesting police brutality and racism. Words on the right refer more broadly to social forces, violence, consequences, and other international concerns. These may be more indicative of commenters approaching the issue from the political right - although we caution the researcher against reading too much into any single finding without replicating their study and performing additional in-depth research.

Removing Outliers

While the first visualization produced out of this particular YouTube comment dataset is pretty legible, some of the words at the bottom side corners of the visualization (indicated by red ovals) are largely irrelevant to the analysis. We already removed even more extreme outlier words from our dataset earlier, in the Remove Stopwords and Punctuation section. Even after cleaning your dataset, it is common for the process of Wordfish modeling to dredge up additional outlier words that you may wish to remove from the visualization.

While the inclusion of these outliers words have little effect on the overall model’s structure, they distract from visualizing the more important words (especially like those enclosed by the green ovals in Figure 3). Unless the researcher has good reason to believe outlier words are meaningful to their analysis, it is better to remove these points and maximize focus on more densely populated parts of the visualization.

Below, we provide code to remove additional outlier words (for our data, those circled in red in Figure 3). After removing the outlier words, this chunk of code re-runs the Wordfish model and produces a new word-level visualization:

more_stopwords <- c("edward", "bombed", "calmly")

dfmat_all <- dfm_remove(dfmat_all, pattern = more_stopwords)

tmod_wf_all <- textmodel_wordfish(dfmat_all, dispersion = "poisson", sparse = TRUE, residual_floor = 0.5, dir=c(2,1))

summary(tmod_wf_all)

wf_feature_plot_more_stopwords <- textplot_scale1d(tmod_wf_all, margin = "features") +

labs(title = "Wordfish Model Visualization - Feature Scaling")

wf_feature_plot_more_stopwords

Figure 8. Visualization of Wordfish model showing relative placement of features (words) with outliers removed

For this lesson, we removed three additional stopwords, so that the center part of the visualization is of greater interest. Again, it is the words that project off the sloping sides of a balanced Wordfish visualization that are the most descriptive of the primary dimension. Those very far down on the vertical axis may be polarizing, but they are also very rare, and therefore are unlikely to be as explanatory of that dimension.

You can export this visualization as a .jpeg image file by running the following line of code:

ggsave("Wordfish Model Visualization - Feature Scaling.jpg", plot=wf_feature_plot_more_stopwords)

Note that the image quality from ggsave isn’t always ideal. You may have better results using the zoom button in RStudio to zoom in on your visualizations, and then manually saving them as .jpeg image files by right clicking on the pop-up window, or by taking a screenshot.

Analyzing the Visualization

Visualizing partisanship can be a useful means for discourse analysis of a corpus’s political polarity based on the most salient, opposing ideological stances.

The second method of visualization presented in this lesson displays data at the document level. This visualization highlights opposing sides of the corpus’ salient topic by coloring each document’s unique plot point, arrayed along the horizontal scale.

To create this color coded visualization, run the following code:

wf_comment_df <- tibble(

theta = tmod_wf_all[["theta"]],

alpha = tmod_wf_all[["alpha"]],

partisan = as.factor(tmod_wf_all[["x"]]@docvars$partisan)

)

wf_comment_plot <- ggplot(wf_comment_df) + geom_point(aes(x = theta, y = alpha, color = partisan), shape = 1) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("blue", "red")) + labs(title = "Wordfish Model Visualization - Comment Scaling", x = "Estimated theta", y= "Estimated psi")

wf_comment_plot

Based on the partisan indicators we assigned to the data, blue plot points represent comments from left-leaning channels, and red plot points represent comments from right-leaning channels.

Note in the following visualization that the colors are not clearly grouped!

Figure 9. Visualization of WordFish model showing relative comment placement color-coded by partisanship of video channel

Figure 9 shows the document scaling components of the model (where each document is a single comment). The position of each document is described by two model parameters, which are directly parallel to the ones discussed above in Figure 5, although for documents they are referred to as alpha and theta. The horizontal axis (theta) shows the scaling of comments, which is parallel to the horizontal scaling of features. The theta parameter describes how polarized each comment is, and in which direction. The vertical axis (alpha) reflects a fixed effect for document length - that is, how many features (words) remained in each comment following preprocessing. As long as documents have ~10 or more features, they can be meaningfully modeled; this tutorial removes documents shorter than this threshold during preprocessing, though you may note that there is clear length-based striation towards the bottom of the model where the shorter comments appear.

The roughly even distribution of red and blue plotting symbols throughout the model suggests that the latent (horizontal) dimension modeled by Wordfish does not counterpose the content of comments from left-leaning sources against those from right-leaning sources. Instead, that dimension describes different aspects of the political debate, which suggests that users from a variety of ideological standpoints are contributing to comment threads on the videos in this corpus. In other words, if comments posted on right-leaning videos were consistently and systematically different from comments on left-leaning videos, we would expect clear clustering and separation. The fact that this divide does not manifest in the visualization suggests that left-leaning and right-leaning video channels are receiving comments from people spread across the political spectrum.

The small cluster of blue out to the far right of this visualization suggests that some of the most polarizing comments were added on videos from left-leaning channels. Otherwise, based on this visualization, the channel’s political affiliation does not seem to be a strong predictor of the commenters’ political positions.

Conclusion

In this lesson, you have learned how to download a large corpus of YouTube video comments, process the text data, analyze the comments using the Wordfish algorithm, and produce several insightful visualizations. You can reuse the code in this lesson on your own YouTube comment dataset - to download the code for easy re-use, see the attached R script.

If you used this lesson’s data, you can tell from these three visualizations that a broadly similar set of topics is discussed on comment threads for both left-leaning and right-leaning YouTube videos focused on police brutality and police funding. You have also seen that you can interpret these visualizations to discover which words determined the scale created by the Wordfish model, and which videos contributed to each pole of that scale.

These visualizations, and more granular analyses of the Wordfish model, will enable complex interpretations of textual meaning. The fact that Wordfish can be useful for understanding the strange type of discourse that appears in YouTube comments is a fascinating revelation of its own.

Endnotes

- André, Virginie. “‘Neojihadism’ and YouTube: Patani Militant Propaganda Dissemination and Radicalization.” Asian Security 8, no. 1 (2012): 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2012.669207.

- Ledwich, Mark, and Zaitsev, Anna. “Algorithmic Extremism: Examining YouTube’s Rabbit Hole of Radicalization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.11211 (2019). https://arxiv.org/pdf/1912.11211.

- Ribeiro, Manoel Horta, et al. “Auditing radicalization pathways on YouTube.” Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (2020). https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.08313.

- Markmann, S., and C. Grimme. “Is YouTube Still a Radicalizer? An Exploratory Study on Autoplay and Recommendation.” In: Bright, J., Giachanou, A., Spaiser, V., Spezzano, F., George, A., Pavliuc, A. (eds) Disinformation in Open Online Media. MISDOOM 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12887. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87031-7_4.

- Hosseinmardi, Homa, et al. “Examining the consumption of radical content on YouTube.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 32 (2021): e2101967118. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2101967118.

- Thorson, K., B. Ekdale, P. Borah, K. Namkoong, and C. Shah. “YouTube and Proposition 8: A Case Study in Video Activism.” Information, Communication & Society 13, no. 3 (2010): 325–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180903497060.

- Bowyer, Benjamin T., Kahne, Joseph E., and Middaugh, Ellen. “Youth Comprehension of Political Messages in YouTube Videos.” New Media & Society 19, no. 4 (2017): 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815611593.

- Spörlein, Christoph, and Schlueter, Elmar. “Ethnic Insults in YouTube Comments: Social Contagion and Selection Effects during the German ‘Refugee Crisis’.” European Sociological Review 37, no. 3 (2021): 411–428. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa053.

- Zimmermann, D., Noll, C., Gräßer, L., et al. “Influencers on YouTube: A Quantitative Study on Young People’s Use and Perception of Videos about Political and Societal Topics.” Current Psychology 41 (2022): 6808–6824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01164-7.

- Murthy, Dhiraj, and Sharma, Sanjay. “Visualizing YouTube’s comment space: Online hostility as a networked phenomena.” New media & society 21.1 (2019): 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818792393.

- Yun, Gi Woong, Allgayer, Sasha, and Park, Sung-Yeon. “Mind your social media manners: Pseudonymity, imaginary audience, and incivility on Facebook vs. YouTube.” International Journal of Communication 14 (2020): 21. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/download/11034/3131

- Yang, Yu, Noonark, Chanapa, and Donghwa, Chung. “Do YouTubers Hate Asians? An Analysis of YouTube Users’ Anti-Asian Hatred on Major US News Channels during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Global Media Journal-German Edition 11.1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.22032/dbt.49166.

-

Here is a selected bibliography: ↩

-

Here is a selected bibliography: ↩

-

Here is a selected bibliography: ↩

-

Related work on analyzing YouTube data developed out collaborations among graduate students at Temple University Libraries’ Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, which produced a series of relevant blog posts introducing a range of methods for retrieving and analyzing YouTube data. For more info, see: 1) the authors’ introductory blogpost on Temple University Libraries Scholars Studio blog, How to Scrape and Analyze YouTube Data: Prototyping a Digital Project on Immigration Discourse; 2) Nicole Lemire-Garlic’s blogpost To Code or Not to Code: Project Design for Webscraping YouTube; 3) Lemire-Garlic’s Computational Text Analysis of YouTube Video Transcripts; and 4) Ania Korsunska’s Network Analysis on Youtube: Visualizing Trends in Discourse and Recommendation Algorithms. ↩

-

It is not possible to fully cover the benefits and limitations of Wordfish in this lesson. For more detail, see Nanni, et al. (2019), as well as Luling Huang’s excellent blogpost on the Temple Libraries’ Scholars Studio blog, Use Wordfish for Ideological Scaling: Unsupervised Learning of Textual Data. ↩

-

In lieu of installing R and RStudio on your computer, you may use the cloud version of RStudio: Posit Cloud, a web-based version. This lesson will run on Posit Cloud. However, depending on how often you use the cloud version, you may require a paid subscription. ↩

-

For introductory information about installing R packages, see Datacamp’s guide to R-packages. ↩

-

Slapin, Jonathan and Sven-Oliver Proksch. 2008. “A Scaling Model for Estimating Time-Series Party Positions from Texts.” American Journal of Political Science 52(3): 705-772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00338.x ↩